War Correspondents

By Tom Fels ’67

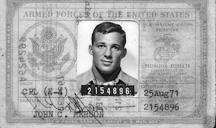

John Merson '66 was on the Amherst wrestling team |

As the year 1965 opened, the lives of John Merson ’66 and his classmate Marshall Bloom seemed to be continuing along their normal course. Merson, a devoted athlete, conscientious scholar and dedicated public citizen, had been elected president of the Amherst student government. To many he was a model, an ideal of the well-balanced, even-tempered student.

Bloom, energetic and politically oriented, edited the Amherst Student and was immersed in a variety of activist causes, including the civil rights movement. He would also originate an exchange program, funded by the Merson-led student government, between Amherst and historically black colleges.

The two classmates were part of an intellectually adventurous group of students who shared a commitment to testing their passionate views. From this group came the core of the era’s two most important activist groups at Amherst: Students for Racial Equality and the small but intense chapter of the fledgling Students for a Democratic Society. Though I was in the class behind, my interests soon drew me to this group of students, several of whom became my friends.

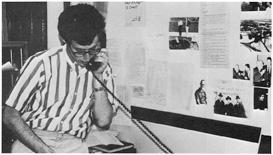

Marshall Bloom '66 |

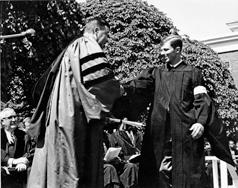

Late in his senior year Bloom helped organize one of the earliest nationally recognized protests against the Vietnam War, held on the occasion of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s visit to campus in June 1966 to receive an honorary degree. The college had announced the McNamara appearance only a few days in advance, and on short notice a group of students (Bloom and me included) held a silent protest and printed and released a public statement. A number of members of the Class of 1966 wore white armbands to their graduation, several walked out when the secretary rose to speak, and one refused his diploma. A picture of the protest appeared on the front page of The New York Times.

John Merson did not attend the protest—or Commencement. In spring 1965 he had surprised most at the college by announcing that he would leave Amherst to join the U.S. Marines. His activist friends were shocked, but so were the war supporters on campus, who had assumed that, like the others in his circle, Merson opposed the war.

At their graduation, some members of the Class of 1966 wore white armbands to protest Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara's arrival on campus to receive an honorary degree. |

Last year Merson wrote a book, War Lessons: How I Fought to Be a Hero and Learned that War is Terror (North Atlantic Books), that prompted me to read the Vietnam-era correspondence between Merson and Bloom in Archives and Special Collections in Frost Library. I studied the letters while planning a recent symposium that focused in part on the farm commune that Bloom started in 1968 and the underground press in which Bloom and the farm played a role. The symposium, held at UMass this past October, marked the 40th anniversary of the farm’s first year—and of Bloom’s death on Nov. 1, 1969.

About a dozen letters survive between Bloom, who wrote from various fronts in the conflicts of the 1960s (including the Amherst area, London and Washington) and Merson, who was in the actual trenches of Vietnam. In the letters excerpted here we see the conflicts of the 1960s enacted before us through the attempts of two young men to maintain their friendship and understanding while at the same time differing on some of the important issues of the day.

June 8, 1966

Dear John,

Please forgive the delay in writing. I got your letter when I returned from my last visit to Alabama, just in time to start commencement week. As you know, I believe, this was an especially hectic time, what with the visit of the Secretary of Defense and all, in addition to the heavy schedule. If you want more information about his reception, please write and ask me. I understand that mail is, for some reason, censored, and this is, I suppose, a political area. Suffice it to say that all your friends were involved in one way or another....

It was good, yet very sad to leave Amherst the way we did. I love the school very deeply.... Precisely because of this love, it is and was harder for me to [do] certain things which I must because there are even higher priorities.

Do take care of yourself. Godspeed. Please come back safely.

[Marshall]

The Alabama reference is probably to Bloom’s work on his senior thesis, which focused on relations between Jews and blacks in Selma, Ala. Whether the two continued, in June and early July, to discuss the demonstrations is not known, since the letters from that period seem to have been lost.

In the next surviving letter, written from Vietnam, Merson talked about the role of race in relationships with his fellow Marines.

20 July [1966]

Dear Marshall,

... I’m in a fire team with three Negro Marines. One is from Philadelphia, one from Detroit, and one from Chicago. I say Negro because I am quite aware of the racial difference. At the same time I try to repress this awareness: We never discuss civil rights, racial problems, or even bits of news such as the rioting in Chicago. They would, I believe, just as soon not discuss such matters, and I feel the same way.

... [I]n a low pressure way [though] ... we do come to know something about each other.…

We share stories, uniforms, weapons, work details, letters, packages from home, worries and hopes and sometimes a dream. We build bunkers, dig foxholes, fill sandbags together, stand watch at night, are wakened by the man who is tired and needs sleep, and when our own watch is done, we gently touch the shoulder of our own relief. We call for help when we hear strange sounds, see Cong, or get sleepy or lonely. And we leave each other alone a lot, sometimes in selfishness, sometimes in consideration for another Marine’s privacy, or his attention to some personal matter.…

Life here continues at a fairly casual pace, with occasional day and night patrols into “Cong country,” none of which have been dangerous.... Best wishes, and ... thank you for the wonderful Schimmelpennick cigars.

John

Two weeks later Merson commented on the advent of the Black Power movement and on the hopes of Elliott Isenberg ’66 to build an interracial movement of the poor. He then turned to Vietnam:

2 August [1966]

Dear Marsh,

... Our heavy commitment in Vietnam places a great strain on our sense of priorities: Witness the violence in Chicago. Have you read of the proposed “negative income tax” as an answer to American poverty? The $5-8 billion needed to implement it is going into military spending.

Today amid pouring rain we went on a 7-hour patrol, and tonight we’ll be out in it again all night, setting up ambushes. Our own area is pretty secure now. Next month we might become a battalion afloat in the South China Sea, used as a force in readiness, a strike force for operations all throughout Vietnam.

Have you decided upon your plans for the coming year?

Best wishes,

John

Merson in Vietnam in 1967. "What I liked best about being a foot soldier was camping—living on the land, finding grapefruit and coconuts and bananas, trading our food to the villagers for bowls of hot vegetable soup and the intimacy with my fellow soldiers," Merson says. "When I look at this picture, I remember often being happy there." |

As Merson explains in his book, his motivation for joining the Marines had to do with proving something to himself and his family (“How I fought to be a hero”) but was also, in a sense, a firsthand investigation of human conflict (“and learned that war is terror”).

By the time of Merson’s next letter, Bloom was a student at the London School of Economics, where he would continue his high-profile career as a student activist—in this case, against Apartheid. Like the McNamara protest, the demonstrations he led at LSE became international news.

26 December [1966]

Dear Marshall,

…

Things are very slow here; our main activity is patrolling our company TAOR (tactical area of responsibility). It’s routine work, not difficult, not the least dangerous, and often quite boring. The Vietnamese are silent, and the Cong faceless. We are all well insulated, our prejudices fur-lined and our emotions waterproofed.

Have you read On Aggression by Konrad Lorenz? If not, I should like to recommend it….

With best wishes,

John

Bloom appeared on the cover of the underground newspaper The East Village Other in November 1967. |

Lorenz’s book must have resonated strongly with Merson. Using animal studies to reflect on the behavior of man, it sets the struggle for territory and domination in the larger context of nature, and it reflects on topics that confront a soldier daily, such as personal bonds and social organization.

Merson frequently engaged in this type of philosophical probing with Bloom. In the following three letters, Bloom responded in kind. The first was written while on a visit to Bloom’s hometown of Denver:

2/20/ [1967]

90 So. Ivy

Denver, Colo. 80222

John,

Thank you very much for your good letter. I think you were exactly right about everything you said about Amherst and about the demonstrations, and it pleased me that someone else, on his own, felt the same.…

It is strange that I even go so far as to admire with you President Plimpton on that day. He did conduct himself with dignity and honor. It is a shame that his behavior is not always on that high level.… He issued a statement several days before graduation … about separating McNamara the man from his policies. This is frightening and false doubletalk; it is also the same argument [Adolf] Eichmann’s lawyers used.…

I gather you are not entirely happy that your life is “exceedingly slow” and that you are “in no danger.” Boredom is not the worst human condition; there are many that are worse, and more final.… [S]omeday you will have so much more to contribute to the world than you ever possibly could on the battlefield.…

Please do be careful. God be with you.

[Marshall]

The earlier letter from Merson appears to have been lost, but another, from Merson to his father in the summer of 1966, describes the Marine’s views of the McNamara protest:

I received articles on McNamara’s appearance at Amherst from several different sources, and comments from friends at Amherst. In the end I decided that the picture of students protesting ... was quite a pleasing one: it showed students in a decidedly political frame of mind, using whatever opportunities might present themselves, to give voice to political opinions—idealists, yes, but with a pragmatic bent.... And certainly McNamara himself is shrewd enough to recognize political action as such without mistaking it for “rudeness,” a word which is more properly used to describe the style than the substance of action.

Bloom believed in consistency: one’s actions must be in line with one’s beliefs. Merson saw action as separable from character, and today he numbers himself among those who respect McNamara for admitting his mistakes about the war, and not among those who, following Bloom’s line of thinking, will never forgive McNamara for not speaking out sooner. In the same vein, Bloom, in his comment about life “on the battlefield,” was set on convincing Merson to raise his sights and to save himself for post-war work. They eventually came to agree on that point.

Three months after Bloom sent the letter from Denver, Merson completed his tour in Vietnam.

[Undated, late spring 1967, likely sent from London]

John,

It’s wonderful to hear you are at last safely out of Vietnam.... I’m superstitious and it’s just when you seemed close to safety that something might have happened....

I have had on my mantel since 21 January a letter I ... refused to send. It was the first letter that talked very much about the politics of the war you were—and are—involved in directly. There came a point when I could not write you another kind of letter, and while you were in Vietnam, while your own life was being risked, I could not send my letter.

Now, though, I must speak as someone who loves America, who is sickened at the thought of what we are doing in Vietnam and to the Vietnamese, and, I hope, as your friend....

Elliott and I today signed a pledge, along with some other friends, which I fully intend to honor. I have pledged to refuse military service while the United States is fighting in Vietnam, and to encourage and assist other men of draft age to resist as well....

Instead of educating men to go to Vietnam, you should be teaching them not to. Or refuse to teach them. Or try to speak at high schools and colleges on what the U.S. is doing and how easy it is for an individual to get involved in what the U.S. is doing. For all of this there may be serious penalties for you, but I can’t help thinking that that, too, may be part of the atonement for what you have participated in.

Of course, in our own ways, we have all participated. We have bred the culture that made it possible for you to be sent there, we have given the money that paid your salary and supplies.... That is why I must actively resist. Surely it should be equally true for you....

Forgive me if this letter is harsh and unsympathetic. But beyond our own personal needs, weaknesses, desires, and hopes, there is this enormously monstrous thing we have done and keep adding to.

Bloom enclosed the earlier letter:

21 Jan 67

John,

In the months since you announced your plan of going to Vietnam, I have … avoided discussing the political implications of the act with you.... I continued to think that your motivation, hence justification, … was that which impelled you to leave Amherst and join the Marines…: personal problems felt more deeply than most adolescents. But I realized I was deceiving myself. At the point at which a man holds a gun in his hand then he must be responsible for his behavior.…

Your recent letter to Leonard [Lamm ’66] … was about the good, the helping hand of development, which must and should be done by the U.S. after the war has been “won.”… But it seems to me a simple fact that this has nothing to do with the necessity of waging a war, that these activities could have gone on in 1954 with our earlier ally and friend, Ho Chi Minh, or in 1961, or any time that war in Vietnam ceases.…

I look forward to your reply.… New possible responses by [members of the] military have [recently] become conceivable…The war is now a subject of genuine controversy in the States. … I can only hope your own behavior is in response to your own best convictions.

Sincerely,

[Marshall]

Merson’s next letter, dated June 11, probably crossed with those above, as it contains no reference to his friend’s provocative remarks. From Camp Pendleton in California, Merson commented on the bombing of North Vietnam:

My own view of the situation is that it demands greater subtlety than our own policy is capable of adjusting to.… [T]he revolutionaries seem to hold the key cards, and vast popular support. As we prolong the suffering, North and South, we extend the destruction that ultimately makes democracy unworkable, and drive revolutionaries into the communist camp…. Only negotiations could halt or reverse this situation, negotiations combined with massive aid to a revolutionary South Vietnamese government. We don’t seem able to move in this direction. I’m not interested in U.S. honor, unless by that we express our feeling of responsibility for the fate of non-revolutionary South Vietnamese nationalists. This would seem to be the major obstacle to our speedy withdrawal.

It’s hard to think about these things without having people to talk with about them. [Camp Pendleton] is for me an uninhabited desert, at present. I hope I can just do my job for the next 7 months, then get out. For what, I don’t know, but maybe among different people, some things will seem more clear....

Yesterday I listened to a recording of Churchill’s speeches.... As I tried to imagine what those people must have felt at that time, I was moved to tears repeatedly.…Merson says, "I got this card as I was leaving Camp Pendleton in 1968. All done, all just beginning."Yours,

John

Five days later, on June 16, Merson replied to Bloom’s earlier appeal, saying he’d begun to write publicly about his views of the war and was considering speaking at schools and colleges. “I think I can make effective use of my experience in Vietnam,” Merson wrote, “and your letters have stimulated some new thinking, and, I hope, action, in this direction.”

Bloom, who had left London to become head of the U.S. Student Press Association—a job he would almost as soon leave to found the Liberation News Service—wrote back suggesting groups and activities in which Merson might involve himself, including the Vietnam Summer Project, and continued:

I would also like to discuss your feeling about the military [in your June 16 letter], that you have no quarrel with them because “they are instruments of policy.” … Are men really expected to be the instruments of someone else? To have no thoughts themselves? … There would be no wars if there were not men willing to fight them.

Merson had actually answered that criticism earlier with his more catholic view of the complexity of human conflict. He had also explained, as he does in his recent book, that he believes the answer to armed conflict is the use of peacekeepers, as exemplified by those of the United Nations, a force committed to solving problems rather than exacerbating them.

After the Marines, Merson received his B.A. from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and his M.B.A. from Harvard Business School. He went on to serve as an administrator at a historically black college and then as a consultant to colleges and schools. More recently he has been restoring houses on Nantucket, Mass. In 1995 he began returning regularly to Vietnam, where he continues to involve himself in the reconstruction of the country and the advancement of its people.

Bloom founded the Liberation News Service, a national press service for underground newspapers, and moved it to rural Montague, Mass., where he lived and worked on his farm and operated the printing press and news service from a converted garage. |

Bloom, in the time Merson was completing his education, founded the Liberation News Service, a national press service for underground newspapers, and moved it to rural Montague, Mass., just north of Amherst. In an undated letter probably sent in late 1968, Bloom wrote of living on his farm and operating the printing press and news service from a converted garage—his hands were bruised and scratched, he told his friend, but “mostly it is pleasure and enjoyment.”

Merson traveled to the farm in the late summer of 1969. “He was the happiest I’d seen him in a long time,” Merson recalls of that visit with Bloom. But only two months later, on Nov. 1, 1969, Bloom drove the green Triumph Spitfire he had brought with him from England into a nearby field and ended his life. Friends and colleagues have numerous theories of what brought on Bloom’s suicide. One factor, almost certainly, was a recent call from his draft board.

The similarities between Merson and Bloom are clear: They were both young men of strong moral and social beliefs, and they were both advocates of extreme behavior. When Merson describes Marine life, it sounds communal; Bloom’s career as a peace activist appears to be a form of war. But the soldier who went to the front survived to live a life devoted to healing, education and social justice, while the fighter for just causes allowed himself only a brief career before succumbing to a nexus of forces that led to death. The word peace can have many meanings. Each, here, achieved it in a different way: Merson through work, Bloom in rest.

Tom Fels, who lives in North Bennington, Vt., is the author of a book about the extended family of Marshall Bloom’s Montague Farm, Farm Friends: From the Late Sixties to the West Seventies and Beyond (RSI/Chelsea Green Publishing, 2008) and founder of the Famous Long Ago archive at UMass.

Photos courtesy of John Merson '66, The Olio and Amherst College Archives