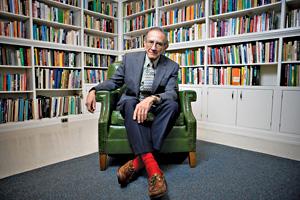

My Life: Allen Guttmann, Emily C. Jordan Folger Professor of English and American Studies

Interview by Caroline J. Hanna

|

Odd how things end up

In his half century on the Amherst faculty, Allen Guttmann, professor of English and American studies, has taught courses and written about American history and literature and the history of sports. In the latter area he has been most prolific: his 10 books on sports history have been praised (and disparaged, he says) in books and essays, online and even in a special issue of the Journal of Sport History devoted to his work. His first sports-history book, From Ritual to Record, initially published in 1978, has been translated into French, German, Italian, Japanese and Korean. His other writings have won prizes from the North American Society for Sport History (twice), the International Society for the History of Sport, the U.S. Olympic Committee and the International Olympic Committee. A graduate of the University of Florida, the University of Minnesota and Columbia University, Guttmann has served as president of the North American Society for Sport History and on the editorial boards of American, British, French and German journals dedicated to sports history and sports sociology. In 2005 he received an honorary degree from the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Belgium. He recently sat for an interview with Amherst magazine.

On the real differences in sports

I was in Germany teaching on a Fulbright exchange in 1968 or 1969 and went to a soccer game in Berlin. I was fascinated that there were 50,000 Germans cheering about this game, when soccer was almost unknown for adults in the United States. That made me think that it would be interesting to compare European and American sports. So I started to do a little research and discovered that the Germans have a very rich tradition of sports history. The more I read, the more fascinated I was. Before long I was looking into ancient Greek sports, medieval sports, sports of every era. That led to From Ritual to Record, in which I argued that the real differences in sports are not between the United States and Europe but between the past and the present. I was so interested in the topic and so pleased with the reception of the book that I just continued to do more research.

On his next major work

I think I’ve just about reached the end. I’ve done 10 monographs, translated three and co-edited a three-volume encyclopedia of women’s sports. When I finish the study of sports and American art that I’m now working on, I think that’s enough. But who knows? It has actually crossed my mind to do a memoir on my 50 years at Amherst because I’ve saved almost every letter I’ve written and received. In fact, I’ve saved things that I’m sure are of no interest whatsoever. You know: letters that say, “We don’t want your article on Saul Bellow. Don’t bother us again.” I put that in a file and saved it. I also have all of the letters I’ve sent people, some of which are 10 to 20 pages long. I have two four- or five-drawer file cabinets full of all of this correspondence.

On his 17,000-item bibliography

I subscribe to probably a dozen different sports studies journals and I’ve assembled a computerized bibliography of everything serious that I’ve read on sports during the 35 years or so I’ve devoted to the topic. The bibliography now has more than 17,000 items. When people ask me, “Can you recommend to me something on Chinese women’s polo or Argentine cricket?,” I can go to my bibliography, do a search and print off a bibliography.

On which sports he follows

I am a sports fan intermittently. When I played tennis, badly, I watched it, avidly. I can be interested in baseball, but only if the Red Sox do well.

On watching the Olympics

I’ve never been to a single Olympic event. When I first tried to get tickets back in the 1970s and ’80s, I didn’t have the influence to get good seats. Then, by the time I had the influence, I decided I’d rather watch on TV. Now I don’t even want to watch on TV because I can’t stand the commercials and the interviews in which the winners are asked if they are glad to have won and the losers are asked if they are sorry to have lost.

As far as members of the International Olympic Committee are concerned, I’ve met [former IOC President Lord] Killanin and had a very unpleasant conversation with him followed by a very unpleasant correspondence. I’ve met [former President] Juan Antonio Samaranch a couple of times, but I still haven’t met [current President] Jacques Rogges. Maybe someday.

On running away from home

I started delivering papers when I was 14. By the time I had graduated from high school, I was making more money than my father. He didn’t want me to go to college, which was part of the reason why I ran away from home when I was 16. Fortunately, I had saved enough money by then to get me started. With what I had saved and with a small loan/scholarship from the state of Florida for prospective high school teachers, I managed to finish my undergraduate work at the University of Florida in three years. They had a wonderful program back then that allowed you to take an exam and get credit for a required course without actually having to take the course. The first two years of required courses were so easy that I just took the exams. After graduation I went into the Army. After that, I went to Columbia University for an M.A. and then to Minnesota for a Ph.D. in American studies.

"This is my first job since the U.S. Army," says Allen Guttmann, pictured here in his early days at Amherst. |

On his first job

Amherst came as an accident. There was a professor at Minnesota named Leo Marx, who was a fantastic, charismatic teacher. The best teacher I ever had. He was snapped up by Amherst, so he left Minnesota and came here. Not long after, in late 1958, the English and American studies departments at Amherst needed—I was about to say “cannon fodder”—a new faculty member. They used to hire and fire people to teach the basic required courses. They were looking for somebody at that point and the impulse was what it had always been in those days: to call up Harvard or Columbia and say, “Send us someone.” If that someone came and behaved himself, then he had the job.

Well, Marx said, “There are a number of American studies programs around the country. Why don’t you look at some candidates from elsewhere?” This was a revolutionary idea at that time, but people were flexible enough to go along with Marx’s suggestion. So Leo called me and told me Amherst was looking for somebody for a five-year job to teach English and American studies and that Minnesota had recommended me. He asked me to come to New York, to the Modern Language Association meetings, to be interviewed. I was a teaching assistant that year, and I told him that I didn’t have the money to fly to New York and stay in a hotel for two or three nights. And that was that, until February of the next year. Marx called me again and said, “We didn’t like any of the people we saw in New York. Would you come to Amherst if the college pays your way?” I came, was interviewed and got the job. Afterwards, though, Marx warned me, “Don’t even dream of staying beyond five years.” Odd how things end up.

This is my first job since the U.S. Army. A couple of years ago, I applied for a visa to visit Russia. The application form asked for the name and address of my present and my previous employers. I was tempted to write down, “Anthony Marx, Amherst, Mass., and Dwight D. Eisenhower, Washington, D.C.”

Top photo by Samuel Masinter '04