Warts and All

|

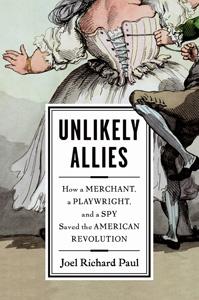

Unlikely Allies: How a Merchant, a Playwright, and a Spy Saved the American Revolution, by Joel Richard Paul ’77 (Riverhead Books, 2009), tells a tale that would be histrionic if it weren’t actual history.

Reviewed by Robert E. Weir

[Nonfiction] What do a cross-dressing chevalier, a double-crossing playwright-turned-diplomat-and-arms-smuggler and a non-French-speaking Connecticut dry goods merchant posted to Paris have to do with the American Revolution? According to Joel Richard Paul, it would have failed without their efforts. So why do history books ignore the roles played by Charles d’Eon de Beaumont, Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais and Silas Deane? Perhaps it is because they do not fit comfortably into national founding myth.

Paul’s gripping and iconoclastic peek at the deep background to the American Revolution is a welcome antidote to Revolutionary War narratives that treat the Founding Fathers as secular saints endowed with an excess of political wisdom, moral character and virtue. In Paul’s tale, Washington is “painfully aware of his own limitations as a military commander,” Samuel Adams is the head of a self-serving political faction, Ethan Allen is a scoundrel of the highest magnitude, Thomas Paine is a libeler, Benjamin Franklin is a lecher who liked to bounce pretty women on his knee, and the Lees of Virginia are a viperous and treacherous lot, more interested in nepotism than victory. Benedict Arnold is practically a piker when compared with others willing to sell the American cause, including Edward Bancroft, once hailed as hero of the revolution but actually a British spy, and William Carmichael, whose silence supported another spy and who may have been one himself.

Paul, a professor and associate dean at the University of California’s Hastings College of Law, slays many sacred cows in Unlikely Allies. Washington crossing the Delaware to attack Trenton was a suitably romantic subject for a 19th-century painting but was inconsequential in the immediate scheme of things and did little to stymie desertions, prevent Burgoyne’s conquer-at-will campaign in the region or outfit a ragtag army that, by early 1777, couldn’t have quelled a London riot. The Battle of Saratoga was less a victory than a monumental act of ineptitude on the part of Gen. William Howe and was not pivotal in convincing France that the rebels could defeat Britain. Deane and Beaumarchais had been at work on that angle for some time, and French support depended far more upon court intrigue than upon the military prowess of Gen. Washington.

Although Paul draws upon recently unearthed Deane letters, historians have known most of what Deane reveals for quite some time. What makes Unlikely Allies such a delight is the panache with which Paul spins his warts-and-all tale. He takes us inside the courts of London and Versailles and reveals levels of deceit and double-cross that read as if we’re guiltily indulging in an overwrought soap opera. The tale he tells would be histrionic if it were not actual history.

Paul writes that “sometimes history happens by accident,” and what more can one say about a revolution whose fate hung upon whether a French chevalier (Beaumont) suspected of being a woman turned over documents incriminating the French king of violating a treaty with Britain? Or that the social climber (Beaumarchais) who negotiated both the return of the evidence and support for the American cause would be best remembered for penning The Marriage of Figaro and The Barber of Seville? Or that the fate of American independence would take place in an environment more riddled with spies than a John le Carré novel?

Deane emerges as one of the very few selfless actors in the comic-tragedy of the American Revolution. His tireless efforts cost him his fortune, his wife (who died when he was abroad) and his reputation. Not only was he the target of false accusations by political enemies at home but his doubt about the ability of the rebels to win and his counsel that a treaty should be negotiated with Britain ultimately cost him a place in the pantheon of American patriots. Paul does not apologize for taking the sheen off of heroes. As he writes, “By placing the founders of our nation on a pedestal, we risk setting up an impossible standard for future generations to follow.” Those reading Paul’s page-turner will surely know better.

Weir, a historian and freelance journalist, is a visiting lecturer in the UMass history department.