The Midwife

Vedam in her kitchen. She is among the most prominent midwife researchers in the world.

When Saraswathi Vedam ’78 first met Carmen Nuñoz, Nuñoz was nine months pregnant and had no place to go. Nuñoz and her husband live near Williams Lake, a remote region of British Columbia. When she realized she was pregnant, she decided she wanted a natural birth, at home. But the nearest midwives were four hours away—and they were booked solid. So, late in her pregnancy, Nuñoz and her husband traveled to Vancouver to find a birth attendant and a place to give birth. “I was looking for a home for a home birth,” Nuñoz says. “It was wild, I guess. But I was determined.”

Nuñoz combed Vancouver for a midwife, while her husband searched for a place they could live for a few months. Eventually she found the Midwifery Group and met Vedam, one of the group’s nurse midwives. Nuñoz told Vedam her story. By then, she and her husband had found an apartment. Vedam listened, then told Nuñoz that if she went into labor before the apartment was ready, she could give birth at Vedam’s house. Not two weeks later, Nuñoz’s son, Luciano, was born in front of the fireplace in Vedam’s finished basement. “She was like an angel, a godmother,” says Nuñoz.

Vedam is a midwife, a term that means “with woman.” She is, literally, with other women when they give birth. She also prepares them through their prenatal periods and tends to them after their babies have come. She has attended births, many of them home births, for 27 years. Nuñoz’s story is typical of the way Vedam operates: She spends long hours with expectant mothers. She listens as they talk. She identifies any problems that might interfere with their sense of security—and therefore with their health and the babies’. Then she does whatever she can to make the birth as healthy, normal, low-tech and peaceful as possible.

In addition to being a practicing midwife, Vedam is an academic midwife—an Amherst- and Yale-educated teacher and mentor—and director of the Division of Midwifery at the University of British Columbia. She’s also a researcher, a prolific writer on what practices promote the safest births and a fierce proponent of a woman’s right to choose where to give birth. What matters, in Vedam’s mind, is what the evidence says: That home birth is as safe as or safer than hospital birth. That midwives catch as many, or more, healthy babies as obstetricians. That only 17 percent of the interventions that doctors use during hospital births have been scientifically proven to work. The Greek physician and writer Soranus, born in the first century A.D., wrote that midwives should “comprehend the art through theory too.” That’s what Vedam does.

I’m so jetlagged when I arrive at Vedam’s three-story Victorian in the Kitsilano neighborhood of Vancouver that I trip and land in a heap in her foyer. Once she has ascertained that only my pride is bruised, she begins reheating Indian leftovers for my lunch. She moves unusually slowly for an American, and despite having been born in Bellefonte, Pa., she doesn’t consider herself one. “I’ve never thought of myself as an American,” she says.

Vedam’s family came to the United States from the Tamil-speaking southern part of India; they are Hindu. Her mother, one of very few Indians living in Pennsylvania during the 1960s and ’70s, drilled into Vedam that she was Indian, that having an identity outside the American mainstream was something to be proud of. Vedam wears kurtas (tunics) and salvars or chudidhars (loose trousers), and—when she feels like dressing like a grownup (her words)—saris. She has a kumkum (a vermillion disk; some people are more familiar with the North Indian term, bindi) on her forehead. Her hair, which began turning gray while she was still in college and is now almost entirely gray, is held back in a braid that’s long enough for her to sit on.

I am not Vedam’s only guest. Also staying here are Nuñoz and the now-20-month-old Luciano, as well as Angela Spencer, a midwife in Victoria. We spend much of the day gathered in Vedam’s kitchen, helping her cook and clean up meals. This is how Vedam’s kitchen has always been: her oldest daughter, Maya Vedam-Miller ’09, wrote her admission essay to Amherst about her mother’s table, the (mainly) South Indian vegetarian food served at it and the guests who routinely gathered around it.

We eat lunch—a black-eyed pea and potato kootu, zucchini kari and sambar over rice—while Vedam tells me about being an academic midwife. She sees patients all day on Tuesdays, women who are pregnant and those who have already delivered. She examines them, gives them books to read and checks their progress with prenatal classes. She asks what they’re eating, whether anything is bothering them, how their partners or families are feeling about their pregnancies and the impending birth and whether they’re exercising. Only the length of the visit—an hour—and the intimacy and breadth of Vedam’s queries distinguishes her prenatal care from most obstetricians’. That, and the two-page list of equipment she asks her home birth patients to have on hand—items ranging from a large covered pot for boiling instruments, to herbs for soothing perineal discomfort, to a rubber ear syringe for the newborn.

Radiating outward from Vedam’s practice work, like spokes, are her other activities that support the growth of midwifery. She keeps a whirlwind schedule. She carries her own course load, guest-lectures regularly in others’ classes, teaches midwifery concepts to family practice and obstetric residents and brings students into her clinic. Monday—the day I’ve arrived—is her research and writing day, the day she tries to sequester herself from other demands. Wednesday she does committee and administrative work. Thursday she tweaks the midwifery curriculum and meets with student advisees. Friday, she says, is catch-up day. “That’s an ideal week,” she says wryly, “and of course it never really works that way, because you have a deadline this day, or a grant deadline, or an announcement that you don’t have funding, and then the media comes in and you have to drop everything and do media interviews. There’s on-call time, postpartum visits, students in crisis. And then somebody goes into labor.”

When a patient goes into labor, Vedam heads to the mother’s house, toting her pre-stocked “birthing bag”: sterile tray, Doppler fetal heart rate monitor, fetoscope, blood pressure cuff, stethoscope, resuscitation equipment, medications, suturing supplies, IV supplies, blood collection, tubes, catheters, scales. Despite the serious-sounding contents of the bag, midwives go to labors with the presumption that birth is a normal process, that healthy mothers at term can expect to deliver their babies safely and peacefully, without medical interventions such as pitocin, epidurals, episiotomies or Cesarean sections. Vedam attends the mother, helping her find comfortable positions, getting her into the tub or shower, talking her through her anxieties, applying acupressure—doing what it takes to keep mother calm and ease baby out. To illustrate how even a small adjustment can make a big difference in a baby’s safe passage, Vedam tells me to press my thumb and first finger together, then try to slide them past each other. I try. They won’t go. OK, she says. How much space would you need to introduce between those two fingers in order to slide one past the other? Not even a millimeter. A hair. That’s how much space you need to find in a mother’s pelvis to move a stuck baby past the pubic bone. I stare at my fingers in wonder.

Though I don’t witness Vedam at a labor, I imagine that she attends births cloaked in the same mantle of calm she wears throughout my visit. (The one exception to this is when she’s driving. Then, she runs yellow lights and pulls, without looking, into traffic. “Midwife driving!” observes her 16-year-old daughter, Sophia, from the back seat, when the driver behind us honks. Vedam once totaled her car after being awake through three consecutive births—more than 36 hours—and she still suffers from back and neck pain as a result.) Midwife driving aside, the stillness that radiates from Vedam is the thing—more even than her long silvery hair or exotic clothing—that most defines her physically. She seems only rarely flustered—and never when she deals with mothers.

Vedam’s first patient on Tuesday is Hanna Tunnicliffe. This is Tunnicliffe’s first visit, at 28 weeks. Tunnicliffe’s pregnancy is unexpected but wanted. She has been having trouble convincing her husband that their baby should be born at home. He trusts her instincts, she tells Vedam, but his brother and his brother’s wife are pro-hospital, and her husband has been swayed.

As the story unwinds, it becomes clear that Tunnicliffe herself has doubts. She says she’s planning to labor “as much at possible at home” and then transfer to the hospital if she feels like it. Vedam tells Tunnicliffe that soon she and her husband will have to commit to a birth plan—either home or hospital. It’s not about the building, it’s about feeling entirely safe. “It’s like having a safe space to go to the bathroom or have an orgasm,” Vedam tells Tunnicliffe. It’s not a good idea to set yourself up for a mid-birth move unless safety requires it. Vedam invites Tunnicliffe to bring her husband to her next visit so they can all agree on a plan.

Later, Vedam points out that only the luxury of the hour-long visit allowed Tunnicliffe’s ambivalence to emerge. Canada pays midwives for only 60 births per year, encouraging small practices and long visits like these. Even when Vedam practiced in the United States, though, she set aside long blocks for patients. Vedam tells me other stories about the value of time: a woman who confessed, 45 minutes into a visit, that she was having serious marital difficulties; another couple whose male partner admitted, after many such visits, that he was an alcoholic and drug user. Midwifery is not just about catching babies, Vedam loves to say.

She uses statistics to reassure and educate her patients. She tells Tunnicliffe that 92 to 95 percent of her patients who plan to give birth at home do so. Tunnicliffe should rid her mind of the idea that transfers to the hospital are emergency situations, says Vedam. Of the 5 to 8 percent of Vedam’s patients who transfer, 80 percent do so because of prolonged labor; the woman can’t stay hydrated or isn’t progressing. “It’s no-drama,” says Vedam. In 27 years of home and hospital practice, Vedam says, she can count on one hand the number of times she was in an emergency situation—and they didn’t even all end up as C-sections. The question of whether a hospital is necessary for a safe birth is, Vedam says, much like the question of whether you ought to purchase earthquake insurance. “Are you the kind of person who buys earthquake insurance in Connecticut? Or only if you move to California? Or not at all?”

Vedam never meant to be a spokeswoman for home birth. “I just wanted to give good, safe care to a few people, teach about it, love women,” she says. “I’m not there to change people’s minds.” It seems, though, that midwifery and home birth need a protector, too, and if Vedam must be midwifery’s midwife, then she is a good and willing one.

“She has made enormous contributions to being a voice for the credibility of home birth as an option for women,” says Helen Varney Burst, author of the seminal midwifery textbook Varney’s Midwifery and professor emeritus at the Yale University School of Nursing. Vedam is among the four or five most prominent midwife researchers, says Burst. Even in that company, she stands out: “She is absolutely unmatched for her comprehensive knowledge of the home birth literature. Any study that has ever been done, anywhere in the world, she knows what’s been written; she has critiqued it. She speaks with conviction, but, marvelously, even when she’s under fire from opposition, she does not get defensive or emotional or irrational. That’s an incredible quality to have. I wish I had it.”

Vedam defends home birth against a backdrop of powerful opposition. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology and the American Medical Association have both taken the position that home births are not as safe as hospital births; Erin Tracy, the obstetrician who wrote ACOG’s position statement, says that even low-risk mothers can encounter unexpected problems. “By the time they come to the doctor, it’s too late for us to effectively intervene,” Tracy says. Media has also weighed in: in September 2009, NBC’s Today show aired a segment titled “The Perils of Home Birth.”

In her defense of home birth, Vedam echoes the rallying cries of U.S. health care reform efforts. Evidence, she asserts over and over, underlies her arguments that home birth is safe. And home births cost less than hospital births with obstetricians. Some big statistics back up this latter assertion: The U.S. C-section rate is 32 percent and rising, says a 2010 National Center for Health Statistics report. (Vedam estimates the C-section rate of her own patients at 4 percent.) Vaginal delivery in a U.S. hospital costs, on average, $7,737, and a Cesarean delivery increases the cost to $10,958, says a 2007 March of Dimes report. By contrast, the average uncomplicated birth costs 60 percent less in a home than in a hospital, says the American Pregnancy Association.

Vedam’s arguments make even more sense when paired with another refrain of the health care debate: The United States spent 16 percent of its GDP on health care in 2007—much more than the average of 8.9 percent for all developed countries—and yet, its infant mortality rates and rates of low-birth-weight infants were both above average (according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development).

Vedam wrote an annotated bibliography of research showing that planned home births have outcomes as good as or better than planned hospital births, with fewer C-sections and other interventions. Crucially, Vedam isn’t arguing that all home births are as safe as hospital births. She’s arguing only about planned home births: A healthy, low-risk mother gives birth with qualified, well-trained attendants, adequate medical equipment and access to hospitalization should it be needed. If your baby is born on the kitchen floor while you’re home alone, that’s not a planned home birth.

Studies that fail to make that key differentiation can make home birth look bad. That’s one of several criticisms that Vedam levels at a famous birth location study, “Outcomes of planned home births in Washington state: 1989-1996” by J.W.Y. Pang and colleagues, in her own article, “Home Birth versus Hospital Birth: Questioning the Quality of the Evidence on Safety,” published in the journal Birth in March 2003. This critique is one of Vedam’s foremost claims to fame; in it, she writes that by pulling women’s birth locations from birth certificate data, the study “is likely to capture the planned home births, but it is also likely to include out-of-hospital births that had no attendant and births with unknown or unnamed attendants.”

Opponents of home birth often note that there is no large study in which mothers are randomly assigned to give birth either at home or in a hospital. Erin Tracy says without such a study, you can’t compare home and hospital outcomes. Therefore, she believes, hospitals should be the default choice for births.

Vedam sees things differently. Many procedures done routinely in hospitals—automatically giving women antibiotics when their waters break, for example, or using C-section to deliver preterm breech babies—have never been subjected to scientific evaluation, she says, pointing to a review, “Effective Care in Pregnancy & Childbirth,” by Murray Enkin and colleagues. Other procedures—such as epidurals or antibiotic eye ointments for newborns—have known trade-offs between their effectiveness and their risks. Still others, like lying on one’s back during labor, or the use of instruments (forceps or vacuum, for example) to speed up delivery, have been proven harmful. Yet most Americans accept without question that procedures done in hospitals are necessary and health-enhancing. We shouldn’t, Vedam says: Any claims made on behalf of the supremacy of either home or hospital must have evidence behind them.

After a 9-to-6 day, Vedam and I arrive home to her kitchen. She asks me what we should have for dinner. Not wanting her to do any work on my behalf, I suggest leftovers. “I’m tired of leftovers,” she says, and begins whipping up a potato-spinach kari from scratch. She lets me wash and cut the spinach.

In addition to everything else she balances, Vedam has four daughters (all born at home), and she is nothing if not with them. Recently, she acquired a webcam, which she uses to videoconference with them at night. On the first night of my visit, the videoconferencing setup is on the fritz, and Vedam can hear, but not see, her daughters Maya, 23, Zoe, 20, and Lakshmi, 18. She is beside herself, demanding that her fourth daughter, Sophia, fix the computer. When Sophia’s efforts finally produce a picture of Zoe, Zoe ducks out of the screen to change into her pajamas, then lets her mother “put her to bed” online. That same night, Vedam stays up late to talk on the phone with Lakshmi, who, Vedam says, is in a rare expansive mood. In the morning, she listens as Maya, a teacher in San Francisco, tells about a boy in her class whom she has managed to reach, against the odds. The delight Vedam takes in her daughters is mutual; Maya writes, in an e-mail, of her mother: “She is brilliant. I mean really brilliant. You don’t see it because she clucks and fusses, always talks to strangers, and has a distressing tendency to harp on why you aren’t wearing earrings (like a good Indian girl). She has bad spatial perception and always loses her cell phone. But she is just so smart, and she thinks and thinks and thinks, and she changes her opinion when she is confronted with new or different evidence.”

Vedam has always been deeply involved with her girls’ lives, says her husband, Jeff Miller ’83. She worked for their co-op nursery school, supported their extracurriculars and marched herself into school to confront any issues that demanded it. It wasn’t always easy. “We have jokes in the family about the number of birthday parties and holiday dinners that she has missed by being called to a delivery, the number of times she has turned up at a party just in time for the cake to be cut,” he says. But she was always there for the things that mattered, and her ability to balance work and home was “immensely important role modeling for our daughters,” says Miller, senior director for clinical pharmacology at Chorus, part of Lilly Research Laboratories.

Miller and Vedam met at Amherst. She recalls first seeing him laid out with allergies, a pillow over his head, unable to more than grunt “hello”; he spotted her at an Indian music concert in her sari and was fascinated, as a suburban white boy, by her. When Vedam transferred to Amherst in 1975, she was the only Indian student and one of only two women of color. Like many women who attended Amherst during those early days of coeducation, she feels that the college had not fully readied itself to admit women. There was no women’s dean, no athletic facilities for women and few women’s bathrooms. A professor once complained in Vedam’s presence that the school “had once been a professional experience and was now a finishing school.” The college also lacked a doctor with gynecological training or contraceptive knowledge, says Vedam. She and a few friends began offering advice to other students about birth control and sexual relationships. This casual undertaking morphed into a peer contraceptive and gynecological counseling service. The group also lobbied to bring a nurse practitioner to Health Services.

There’s an obvious connection between the counseling she did at Amherst and her decision, after some false career starts, to attend Yale, where she earned her nursing degree and a master’s in midwifery. There’s also a connection between Vedam’s willingness to defend and celebrate her Indian and female identities when she was a minuscule minority and her willingness, now, to defend midwifery and home birth from critics.

If Amherst, indirectly, gave her the courage to stand this ground, it also directly recognized her efforts when it awarded her an honorary degree in 2008. When Amherst President Anthony W. Marx gave Vedam the degree, he celebrated some of the most visible manifestations of her work: the Web-based system she designed to collect perinatal data and track home birth outcomes nationally; her contributions as an expert consultant to the Hungarian Health Ministry and Alternatal Foundation as they developed national guidelines for home birth care; and her leadership of both the Homebirth Section of the American College of Nurse Midwives and the Research and Publications Division for the Midwives Alliance of North America. When Vedam was first offered the honorary degree from Amherst, she could hardly believe it. Now, she says, she’s honored by the recognition, pleased that a college she once viewed as “traditional” and “male” would honor the accomplishments of a woman who, in Marx’s words, has made it her life’s work to give a voice to women and babies.

President Anthony W. Marx gives Vedam her 2008 honorary degree.

|

In his presentation of Vedam’s degree, Marx noted that her students had twice nominated her for the American College of Nurse Midwives Excellence in Teaching Award. “She’s a great teacher,” says Tiffany Lundeen, who took Vedam’s intrapartum and postpartum classes at Yale, became her academic advisee, rotated through her midwifery practice and went on to have her first baby under Vedam’s care. “She’s just extremely kind, loving, caring.”

In return, Vedam demands a high level of involvement from her students. “She has very high expectations of herself and of everyone else,” Lundeen says. At Yale, says Lundeen, Vedam required students who attended births to be 100 percent committed. “If the baby needed a dose of vitamin K, then she expected you to drive an hour and give the baby the vitamin K. That was a challenge and also a real blessing of being taught by Saras.”

In advocating for mothers and babies, Vedam draws on lessons from her family. She learned maternity care from her mother, who hosted, cooked for and taught breastfeeding to new mothers in the Indian community. She absorbed principles of midwifery from aunts and cousins who were obstetric providers in India, as she followed them on rounds during summer visits. She learned courage in the face of adversity from her brother, Subramanyam Vedam, who taught prison literacy, raised funds to rehabilitate youth offenders and earned his own degrees, all while serving a life sentence for murder. (She passionately believes in his innocence, and has worked, so far without success, to find a path to appeal.) Her father was a student activist in India during Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance movement and, Vedam says, a gentle and peaceful man in all his human contacts. He died in September 2009, and talking about him brings her to tears. “I miss him,” she says simply.

She channels his nonviolent approach as she works from Canada to unite two unlikely warring factions in U.S. midwifery: nurse midwives and direct-entry midwives (direct-entry midwives do not have nursing degrees). The two groups are often at loggerheads; their enmity is embedded in the modern history of midwifery. Until the 1940s, midwives delivered 80 to 90 percent of the babies in the United States. Then births began moving into hospitals. Midwives fell out of favor. In some cases, they were harassed and driven out of business; some became the victims of witchhunt-like campaigns.

Midwifery took two paths. To maintain legitimacy, some midwives, like Vedam, got nursing degrees and became today’s certified nurse midwives. Other midwives went underground, practicing as “lay” or “direct-entry” midwives. Then, in the 1990s, those midwives, too, developed a certification path: certified professional midwives. (The American College of Nurse Midwives also certifies another group of direct-entry midwives known as certified midwives.)

Certified nurse midwives and certified professional midwives, on the whole, have grave suspicions about each other. Many CNMs feel that CPMs, by including those who have been trained through apprenticeship rather than at accredited schools, are endangering the reputation of midwifery. Many CPMs feel that nurse midwives have sold out to the establishment. Last year, CPMs, backed by the Midwifery Association of North America, applied for recognition as Medicaid providers. The American College of Nurse Midwives wrote a letter to Congress opposing the request.

Vedam belongs to the main professional organizations of both groups. One of her life goals is to reconcile the two groups. This reconciliation, as well as the goal of finding common ground with doctors, helps drive the Consensus Summit she’s planning for next year. The idea, says Vedam, is for doctors and midwives to look beyond their differences. Then they can figure out how to make all births as safe and positive as possible and how to facilitate transfers between home and hospital when they’re needed. Yale’s Burst applauds Vedam’s work: “If this actually works out, and there is a consensus developed, that’s just going to have an enormous impact on not only the professional organizations but on women and their rights.”

Vedam is not the only Amherst student to take an interest in the tensions that tug at midwifery. Chris Bohjalian ’82 published his novel Midwives in 1997. In it, a laboring woman and her direct-entry midwife, Sibyl, are stranded at home when a violent winter storm arises. The woman appears to die in childbirth; Sibyl performs an emergency C-section and saves the baby, but is brought up on criminal charges after her assistant says the mother wasn’t dead when she cut. Though Vedam hasn’t read the book, she doesn’t try to hide her irritation with its premise. “It’s not a true story, and it could never be a true story,” she says. Midwives, she adds, are naturally cautious and don’t take unnecessary risks, like trying to deliver in icy weather.

She illustrates this with a winter storm story of her own. Tiye Omotoye, Vedam’s patient in Indiana, went into labor as the forecast threatened a blizzard. Omotoye had planned a home birth, but Vedam, eyeing the forecast, suggested that instead of staying at Omotoye’s house half an hour from the hospital, Omotoye should labor in Vedam’s office, five minutes away. There, they could monitor the weather and decide whether she should stay there or go to the hospital. When the blizzard worsened, Vedam took Omotoye to the hospital, where her baby was born.

Aside from doubting that any midwife would make Sybil’s mistake, Vedam says Bohjalian’s book does a disservice to women by portraying birth as scary and dangerous. Vedam tackled this issue—of how media portrays birth—in her honorary degree speech. Women in North America, Vedam told the Amherst audience, have very few experiences of birth outside of television shows and movies—during which women embarrassingly break their water in public, abruptly go into active labor and are carted off, screaming, to emergency interventions of one kind or another. Celebrities—Madonna, Victoria Beckham, Britney Spears, Gwyneth Paltrow—have elected C-sections in increasing numbers, convincing more women that birth is scary and should be avoided. A UBC study found that among women whose sole exposure to birth was media, only 27 percent described their ideas of birth as positive. By contrast, 72 percent of women who’d witnessed a hospital birth and 82 percent of women who’d witnessed a home birth expressed positive ideas about birth. We know (from evidence) that fear and anxiety during pregnancy and labor contribute to worse birth outcomes, says Vedam. By her logic, fiction like Bohjalian’s is a public health hazard.

Bohjalian is no stranger to midwives with strong opinions of his novel, and he’s not defensive when I tell him Vedam’s thoughts on the book. “Midwives is a novel, and it’s going to frighten some people,” says Bohjalian. (So, he adds, might a novel like Michael Crichton’s Airframe; he’s heard readers say it scared them permanently off flying.) On the other hand, he says, “I’ve also met women around the country who’ve told me they’ve had their baby at home after reading Midwives.” As to whether it’s credible that Sybil, the fictional midwife, attempted Charlotte’s birth during a winter storm, Bohjalian says he leaves that question to his readers. What he will say is that Sybil is a very competent midwife beleaguered by the medical and legal systems around her.

Midwives are less beleaguered in Canada, says Vedam, where home-to-hospital transfers are an accepted reality. When Vedam attends a home birth, her patient’s name goes up on the board at the hospital as soon as labor starts; when the baby is born safely, the word Delivered goes on the board. This gives doctors a gut sense for how many successes stand opposite the few cases that require medical intervention.

|

In Vedam’s clinic hangs a collage she particularly likes, by Connecticut artist Joanne Williams. Called Guidance, it consists of overlapping rectangles of printed, woven fabric. Two miniature red wooden columns support a small canvas, on which is painted an indistinct female figure. At the center of her chest is a red circle, and in the center of the circle is a white bird, possibly a dove. The white bird on the woman’s chest reminds me instantly of another bird on another chest.

Raquel Feswick has many tattoos, but the most arresting is the old-school tattoo that covers her sternum, visible in the deep V of her black Diesel button-down and when she opens her blouse to nurse her 7-month-old, Lylah. The tattoo is dominated by two thrushes, one over each breast; Feswick chose thrushes because they always return home. Feswick herself returned home for Lylah’s birth. Though it was her second home birth, it was her first with Vedam. At first, Feswick thought Vedam seemed cold compared to Feswick’s first midwife, a warm-and-fuzzy type. “She’s a little bit clinical,” says Feswick. “That’s the science side.”

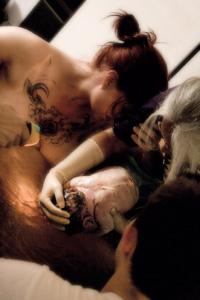

During the birth, though, everything changed. Feswick, who had been very independent during her first birth, rejecting touch through most of her labor, surprised herself by allowing Vedam to press her hips and hold her up. On the wall of Vedam’s office, not far from the antique examining table colleagues gave her when she first opened her private practice, there’s a photo of Lylah’s first moments in the world. Vedam, latex-gloved to near her elbows, pulls the baby, white with vernix, from the swirling waters of the birthing tub. Feswick buries her face in Vedam’s arm, clutching it, her dark head touching Vedam’s silver one. Lylah’s father, Derek Feswick, looks on. Their bodies—Raquel’s, Vedam’s, Derek’s—form a circle around Lylah. If Vedam’s bibliographies, her conferences, her statistics, her criteria—the methods she uses to weigh and make sense of risk—are her science, then this photo, this moment, is her art.

Sarah Auerbach ’96 is a freelance journalist based near Boston and a mother of two. Her last article for Amherst magazine was the Summer 2009 cover story on Zeke Emanuel ’79.

Photos [top to bottom] by Martin Dee, Samuel Masinter '04 and Siska Gremmelprez