"I Was Never a Murderer"

By Rebecca A. Binder '02

|

Dewey Bozella wants to be an actor or a director. He’s a 50-year-old man, a former boxer, tall, with close-cut hair and an easy smile. He’s written and performed in several plays, including an adaptation of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and an original work exploring a prisoner’s hopes and fears. He follows directors Ron Howard (“He makes you think”) and Clint Eastwood (“He got better as he got older”). His favorite movie is Eastwood’s Unforgiven.

Speaking of forgiveness: Bozella’s thought a lot about forgiveness. “How can you ask for forgiveness,” he wonders, “if you can’t forgive?”

Bozella’s been asking himself that question for 27 years. Convicted twice for a murder he did not commit, he went to prison in 1983 and remained there until last year. He spent 22 of those years in Sing Sing, the famous maximum security prison in Ossining, N.Y. For the sake of context: in 1983, Ronald Reagan’s presidency was in its first term, the final episode of M*A*S*H broke television viewership records, Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” music video debuted, and the Baltimore Orioles won the World Series (just ask Bozella, an unabashed Yankees fan, what he thinks about that).

Finally, in October 2009, after the two-year pro bono effort of a team of lawyers led by Ross E. Firsenbaum ’02, Bozella was released. A New York State court vacated the conviction, essentially nullifying it. The judge maintained that Bozella’s constitutional rights had been violated because the prosecution had withheld evidence that could have proved his innocence. For the sake of context: in 2009, Barack Obama assumed the presidency, Michael Jackson’s death led to unprecedented spikes in Internet traffic, and the New York Yankees won the World Series (just ask Firsenbaum, an unabashed Mets fan, what he thinks about that).

Bozella’s childhood was unhappy. Born and raised in the Coney Island section of Brooklyn, Bozella and his 11 brothers and sisters had a rough start. Their father killed their mother, causing the Bozella children to fall into the foster care system. Dewey was placed in a group home, but he kept “running away,” as he describes it, to find and live with his brothers and sisters. The Bozella children ricocheted between thrown-together homes in the Bronx and Queens.

Despite its instability, though, “life was pretty good,” Bozella says, “up until 1977.” That year his brother Ernie, with whom he was living, was killed, and Bozella moved upstate to Poughkeepsie, N.Y., to live with Tony, another brother. Growing up, Bozella had had run-ins with the law. (While his youth record is sealed, public records show a later conviction, in 1980, for attempted robbery.) When Bozella left New York for Poughkeepsie, he took his “street stuff” with him. “Dewey was subjected to a lot of poverty and violence growing up,” says Firsenbaum, a senior associate at Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr (also known as WilmerHale), “and he did a lot of things he’s not proud of. Dewey moved to Poughkeepsie to try to get away from all of that. As soon as he got there, fingers started pointing at him again. He was an outsider, he didn’t really know anyone, and he was in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Bozella’s version of his life in Poughkeepsie is more succinct. “I was not a goody-goody,” he says. “I did a lot of things that I wasn’t proud of. The cops were definitely trying to find a way to get me off the street.

“But I was never a murderer.”

On June 14, 1977, 92-year-old Emma Crapser spent her evening playing bingo at a Poughkeepsie church. At around 11 that night, she returned home to her first-floor apartment, where she walked in on an apparent burglary. The invaders tied Crapser up before brutally beating her, assaulting her and killing her by stuffing pieces of cloth and sharp metal down her throat.

Eleven days later, acting on a tip, the Poughkeepsie police interviewed local usual suspect Lamar Smith about the killing. Smith told police he knew nothing about it. Four days later, though, on June 29, the police arrested Smith for an unrelated burglary. Smith’s story changed while he was being interrogated for this burglary: he told police he saw an 18-year-old Bozella and Wayne Moseley, another teenage ne’er-do-well, on the porch of Crapser’s apartment building on the night of the murder, and that he watched Bozella force the lock to the building’s front door. Smith’s brother Stanley corroborated that story. The police arrested Bozella and charged him with the murder.

With only the Smith brothers’ story, a 1977 grand jury found there was not enough evidence to charge Bozella with the Crapser murder and refused to indict him. Newspaper articles indicate that William O’Neill, the assistant district attorney heading up the prosecution, anticipated as much. “We just need more evidence,” he told the Poughkeepsie Journal before the grand jury convened. The investigation—and the case against Bozella—went cold. In fact, the pendulum of common sense swung away from Bozella’s involvement. In 1978 a man named Donald Wise and his brother Anthony were convicted of, and sent to prison for, a murder strikingly similar to the Crapser killing. The Wise brothers broke into a house three blocks away from Emma Crapser’s and bound, beat and suffocated Mary King, the elderly woman who lived there.

But in 1983, with the Crapser murder unsolved, and with Wayne Moseley—who, according to Lamar Smith, was Bozella’s accomplice—in prison on another charge, things suddenly changed for Bozella. That March, with nine years left on Moseley’s sentence, the district attorney’s office offered Moseley a deal: in exchange for testifying against Bozella, Moseley would be appointed an attorney who would file a motion to vacate the judgment against Moseley, and the prosecution would not oppose the motion. Essentially, the DA’s office offered Moseley a get-out-of-jail-free card if he fingered Bozella for the Crapser murder.

Now, armed with two pieces of evidence—the Smith brothers’ story and Moseley’s bargained-for testimony—the DA’s office had the police re-arrest Bozella and charge him with murder. After hearing testimony from the Smith brothers and Moseley, a new grand jury indicted Bozella for the Crapser murder. As agreed, Moseley was released. For good measure, Lamar Smith, who at the time of his testimony was also in prison for an unrelated conviction, was also released, a month later, on the district attorney’s favorable recommendation.

A juggernaut quickly formed. In April 1983, while Bozella was awaiting trial, the girlfriend of Anthony Wise—who, with his brother Donald, had been convicted of the similar King murder—told police that Donald Wise had killed Crapser, documents show. Two months later the police matched a fingerprint from the inside ledge of Crapser’s bathroom window to Donald Wise. Still, O’Neill pressed forward with Bozella’s prosecution. At the 1983 trial, O’Neill argued that Bozella had entered Crapser’s apartment through the building’s front door. The defense countered that there was no physical evidence, that there were no credible witnesses and that the fingerprint had to mean that Donald Wise had committed the murder.

Dewey Bozella was convicted of Emma Crapser’s murder in December 1983, on a Friday afternoon. “When the case came back,” Bozella says, “I thought I’d just walk in and walk out. You had nothing in 1977, you have nothing now, what’s the problem? When I was convicted, I fell to the floor and started crying, screaming that I didn’t do it. When I heard the words, ‘life sentence,’ I thought, ‘Don’t take my life. That’s all I’ve got.’

“I was angry and I was bitter—I was a man with no mission. For years, I didn’t do anything.” Eventually another prisoner—“my man Sharif,” Bozella calls him (he doesn’t know his full name)—started bringing him back. “He taught me that the only way I could be an asset to society, even if I was in prison, was to have something, some education, some skills under my cap,” Bozella says. “That’s when my mind started waking up.”

Bozella enrolled in educational and vocational programs and courses offered by the prison. “Dewey had no education,” Firsenbaum marvels. “He had no future, and he was in prison for a murder he didn’t commit. He could have just given up. But instead, he turned himself into an educated man, an empathetic man and a man who’s able to and wants to contribute to society.” Bozella is fiercely proud that, while in prison, he earned his G.E.D., a bachelor’s degree from Mercy College and a master’s from the New York Theological Seminary.

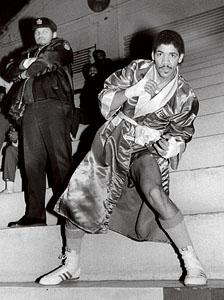

In this 1986 photo, Dewey Bozella, in Sing Sing prison, warms up for a boxing match. He became Sing Sing's reigning light heavyweight champion. |

Bozella even got married during his time in prison. In 1995 he was taking photographs of inmates and their families in the visiting room at Sing Sing when he noticed a woman, another inmate’s sister, and offered to snap a photograph of her with her brother. “And we started talking,” Bozella says. “I told her that I was a boxer (in fact, at the time, Sing Sing’s reigning light heavyweight champion), that I was going to school. She came back to visit me, and we built a relationship little by little.”

“He could talk,” Trena, Bozella’s wife, says. “He walked right up to me, told me all about himself and asked me to visit him. I took a huge risk, but I came back the next week to see him again. About a year after we met, Dewey asked me to marry him.” He did it the old-fashioned way: “I snuck her dad in before I proposed. I wanted to ask him for his blessing.”

Bozella never gave up on fighting his sentence. In 1989 he successfully argued that, during jury selection for the 1983 trial, prosecutors used their preemptory challenges to exclude potential jurors on the basis of race, thus violating his rights under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Yet while the court granted him a new trial as a result, Bozella was convicted of Crapser’s murder a second time, in 1990.

“One of the hardest things to do is to get someone to believe you,” Bozella says, describing the many letters he wrote to the Innocence Project from his jail cell after his second conviction. In 2007 the organization, which is dedicated to exonerating wrongfully convicted people through DNA testing, took notice. The Innocence Project passed the case on to WilmerHale, and Firsenbaum, who typically practices securities litigation and complex commercial litigation, was immediately interested. “I saw an e-mail about staffing a wrongful conviction case,” Firsenbaum says, “and I jumped at the chance. When I was at Amherst, I saw Peter Neufeld from the Innocence Project present with an exoneree in the Red Room. Since then, I’d wanted to do this kind of work.”

Firsenbaum, a native of Queens, N.Y., who now lives and works in Manhattan, is in many ways a typical young lawyer at a large, powerful firm. He works long hours and frets over his cases. His schedule is especially booked these days, as he and his wife, Amanda (Bronfman) Firsenbaum ’02, recently welcomed their first child, a daughter. Firsenbaum represents major investment banks and financial institutions. A double major at Amherst in psychology and law, jurisprudence and social thought, he says that so far, his practice has exceeded his expectations. And yet, during his day-to-day practice, Firsenbaum thought often about the day he sat in Converse Hall’s Cole Assembly Room listening to the Innocence Project exoneree. “I saw the impact the Innocence Project had on this man’s life,” Firsenbaum says. “Their client was rotting in prison for a crime he had not committed. They saved his life. What greater good could there be than that?” Rebekah Coleman ’02, a close friend of Firsenbaum’s, also remembers the panel. “Ross dragged me to the Red Room,” she says. “And it was absolutely eye-opening. It’s striking to be faced with that kind of injustice.” Firsenbaum had wanted to be a lawyer since his first year at Amherst. “We would sit and watch The Practice together in my room,” Coleman says. “Ross would analyze the case on that week’s episode and pick it apart into all its pieces.”

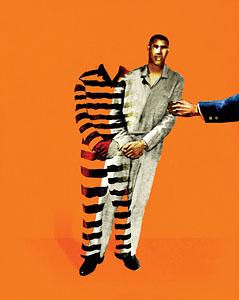

Ross Firsenbaum '02 sits beside Bozella in court. "Ross couldn't just put this case down at night and go home," a colleague says. "Dewey's case weighs on you." |

“Ross spends long days doing billable work,” says Shauna Friedman, a senior associate at WilmerHale who worked closely with Firsenbaum on Bozella’s case. “But Dewey’s case was personal. Ross couldn’t just put this case down at night and go home. Dewey’s case weighs on you, and his pro bono lawyers were probably his last hope.”

Firsenbaum had only two years of practice under his belt when he took the lead on Bozella’s case, planning out the legal and factual arguments he would need to win a motion to vacate the conviction. Bozella first met Firsenbaum and his team in the winter of 2007, shortly after being transferred to Otisville (N.Y.) Correctional Facility. Bozella describes Otisville as “a retirement home for people who had lost hope,” and to hear Firsenbaum describe the place, it sounds like he agrees. “This was my first time inside a prison, and it was surreal,” Firsenbaum says. “It was a cold, dreary winter day. We left the highway for a one-lane road, and then we passed a small town, and then it was just barren. Then, out of nowhere, this prison just appeared, with nothing around it. We met Dewey in a very small room, and we were sitting on these short wooden chairs, like you’d find in a kindergarten classroom.” Firsenbaum remembers the chairs because Bozella, who is more than 6 feet tall, looked so uncomfortable in his. “Seeing him sitting in that tiny chair in that tiny room, with his legs cooped up beneath him, looking right into my eyes and telling me his story, I’ll never forget it.”

“When Ross walked in,” Bozella says, “I noticed that he was young. You think of lawyers as being older, having white hair. But I didn’t care about that; I didn’t care that he was a younger guy. What I cared about was that Ross was listening to me, that he believed me and that he could help me. He sat across from me and he asked questions, and they were the right questions. I knew right away that he was a smart man, a caring man, that he understood and that he’d do whatever he could for me.”

Firsenbaum and his team began the long and contested process of tracking down, requesting and reviewing old case files, interviewing witnesses and piecing together the answers to 30-year-old questions that had never been fully resolved. The pro bono lawyers filed written request after written request for access to police and DA records. “They fought us on almost every item,” Firsenbaum contends. “We had discussions about narrowing the scope of the subject of the requests, about restrictions they wanted to place on which pieces of a file we could and couldn’t see and about whether such old records were even accessible and hadn’t been destroyed.” Finally invited to review and copy the files they’d requested, the lawyers spent a day hovering over a copy machine in the district attorney’s office in Poughkeepsie. They returned to New York with boxes of materials and reams of paper that they hoped would set Bozella free.

Firsenbaum was surprised when retired police lieutenant Art Regula, the lead investigating officer who had testified against Bozella at both trials, agreed to Firsenbaum’s request for an interview. “Dewey felt that Lt. Regula had a vendetta against him,” Firsenbaum says. “We went in with the mentality that he was our opposition.” Firsenbaum was wholly unprepared for what happened next. Firsenbaum traveled to Regula’s house, sat at his dining room table and started to thumb through his notes. “I hope you don’t mind,” Firsenbaum remembers Regula saying before the lawyer could start on his prepared questions, “but I refreshed my recollection before you got here. I took out my case file and reviewed it.”

Firsenbaum was shocked. “Needless to say,” he laughs, “there weren’t any questions in my outline about him saving a 30-year-old case file.” Firsenbaum proceeded cautiously, asking Regula if it was customary for police officers to save their case files at retirement. “No,” he remembers Regula saying. This was the only file the police officer had kept. There was something wrong with the case, Firsenbaum says Regula told him, and the police officer always thought someone would come around one day asking about it.

Regula has mostly stayed out of the public eye since Bozella’s release. A local newspaper reporter spoke with him on the day after Bozella finally walked free. In the Oct. 29, 2009, interview with the Poughkeepsie Journal, Regula told a reporter that he began to doubt Bozella’s conviction when Bozella flatly rejected a plea bargain shortly before his 1990 trial. When asked if Bozella’s release was just, Regula answered, “Absolutely. Guilty or not, he served more time [than most other convicted murderers].”

Inside Regula’s case file—and in records and on tape recordings that they collected from the police department and DA’s office—Firsenbaum and his team recovered four critical pieces of evidence, none of which had been disclosed by the prosecution to Bozella’s original lawyers and all of which contributed to the plain-as-day conclusion of Bozella’s innocence.

First, Firsenbaum’s team found statements made by Emma Crapser’s upstairs neighbors during the original investigation of her murder. The statements shed serious doubt on the prosecution’s theory at trial that Bozella had broken into Crapser’s apartment through the building’s front door. In fact, the statements made clear, people were leaving and entering the building through its front door over the course of the entire night of the murder. To a man, none of them saw Bozella, none of them heard anything and none of them noticed anything unusual about the supposedly broken-in front door.

Second, Regula’s file gave additional weight to the defense’s theory at trial: that Donald Wise had broken into Crapser’s apartment through the bathroom window, in an alley next to the building. In an affidavit that Firsenbaum used to support his argument to overturn the conviction, Regula stated that during the police investigation, a next-door neighbor told officers she heard the garbage cans in the alley—located right underneath Crapser’s bathroom window—rustling on the night of the murder. The neighbor’s observation was never put in writing and was never part of the district attorney’s report.

Third, knowing that Donald Wise had been convicted of the similar Mary King murder, Firsenbaum pored over the King file, where he found a report on a third, similar attack that had occurred in the same time span and that police had also linked to Wise. The police had used the third attack to try to show that Wise used a common modus operandi in carrying out the King murder. Firsenbaum wondered why, if police had linked Wise to the King murder and to the third attack, they didn’t extend that logic to exculpate Bozella and shift the spotlight onto Wise.

Fourth, and most important, Firsenbaum found a critical tape recording in the King file. As Bozella’s defense had noted in trial, Wise left a fingerprint on the inside ledge of Crapser’s window. As it turned out, a man named Saul Holland was interrogated during the King investigation, and that interrogation was taped. Listening to the tape, Firsenbaum heard Holland say that Wise had recruited him as an accomplice for the King murder, assuring Holland that he “had done this before and gotten away with it,” according to Firsenbaum, who says that Wise then described to Holland the entire Crapser murder. On the tape, though, as soon as Holland begins to relay what Wise said about Crapser, that the interrogating officer interrupts. “We don’t want to get into that,” the interrogating officer tells Holland, according to Firsenbaum, “because we’re liable to get confused.” Armed with this material, Firsenbaum filed his motion to vacate Bozella’s conviction in April 2009, arguing that the prosecution had violated Bozella’s constitutional rights by failing to disclose the four pieces of exculpatory evidence. The Dutchess County Court ruled on Firsenbaum’s motion on Oct. 14, 2009.

“Upon a thorough and careful review of the record,” the extensive October opinion reads, “the court, without reservation, is firmly and soundly convinced of the meritorious nature of the defendant’s application.” The court called Firsenbaum’s legal arguments and the uncovered evidence “compelling, indeed overwhelming,” and vacated Bozella’s conviction. The district attorney chose not to charge him with Emma Crapser’s murder a third time, and two weeks later, Bozella was a free man. “Justice had been served, and I was grateful to have been a part of it,” Firsenbaum says.

“Ross is an incredibly thorough lawyer,” colleague Shauna Friedman says. “He thinks about details very carefully, and he doesn’t miss anything. Here, the tiniest details about what a witness said 30 years ago made a huge difference.”

Firsenbaum’s work for Bozella isn’t over yet. On June 24, 2010, Bozella, represented by Firsenbaum, filed a $25 million civil lawsuit in federal court, alleging that Dutchess County, the City of Poughkeepsie, William O’Neill and Robert DeMattio—the detective who interrogated Saul Holland—all violated Bozella’s constitutional rights.

The lawsuit alleges that county and city policies and customs promoted and allowed illegal and unconstitutional practices, including disregarding Bozella’s right to review evidence that eventually set him free. Investigators received no formal training in the applicable law, the suit claims, and therefore, Bozella argues, he fell victim to individual interpretation of the law by different investigators. The lawsuit states that the county and city maintained a policy of destroying notes taken while investigating a crime—a violation of state law that led to the destruction of evidence that had the potential to prove Bozella’s innocence, according to the suit. Also, the lawsuit claims, there was no mechanism to ensure that evidence collected in one investigation—here, the King murder—was cross-checked against evidence in other crimes—here, the Crapser murder.

The suit claims that O’Neill “initiated and continued the criminal prosecution of Mr. Bozella without probable cause or other legal justification, suppressed evidence exculpating Mr. Bozella and incriminating Donald Wise, failed to investigate known exculpatory leads, and maliciously abused legal process.” Specifically, the lawsuit alleges that O’Neill, among other things, failed to link the King murder and Wise’s third assault to the Crapser murder, failed to tell the grand jury that the fingerprint on Crapser’s bathroom window belonged to Wise and failed to go after Wise for the Crapser murder.

O’Neill told the Poughkeepsie Journal in late June that he did not believe Bozella’s claims had any merit. On June 27, 2010, in an interview about the lawsuit, the newspaper quoted O’Neill as saying, “I’m satisfied with the verdicts [convicting Bozella]. I always was, and I’ve seen nothing to change my mind.”

Just freed, Bozella leaves court with his wife, Trena, whom he met and married while in prison. "I used to think the world owed me something," he says. |

“When I left prison, they didn’t give me a gold watch or anything,” Bozella says. “In fact, I had to give back all my state-owned clothes. All I had left to wear was a T-shirt and some orange jeans. Ross brought me a suit to wear the very next day.”

Watching them together, it’s clear that Firsenbaum and Bozella have a strong bond and a mutual respect that goes beyond their attorney-client relationship. Bozella is open and engaging, but he’s also slightly awkward. When Firsenbaum walks into the room, though, Bozella lights up. He’ll leap from his chair, bound over to Firsenbaum, pump his hand in a hearty handshake and then give him a bear hug. He’ll introduce Firsenbaum to anyone within earshot of his booming voice, and he’ll beam as his lawyer makes the rounds. As Bozella embraces him, Firsenbaum will break into a wide smile, as happy to see Bozella as Bozella is to see him. “Dewey and I will always have a special relationship,” Firsenbaum says. “I grew to respect him, not only for his courage in facing such grim odds, but also for the optimism he has for his future.”

This story has no fairy-tale ending, not yet. “In prison, I was a caterpillar in a cocoon,” Bozella says. “I’m still not flying yet, but I’m better than I was. It’s not that easy to just say, OK, I’m a regular citizen now.” Trena, Bozella’s wife, tells an illustrative story. “One day,” she says in her quiet, high-pitched voice, “Dewey lost a white tube sock. It was pretty soon after he got home. He was tearing the house apart looking for it, and I didn’t understand why. I said, Dewey, it’s OK, we can just get you some more socks next time we go to the store.”

“But the thing about the sock is,” Bozella interrupts his wife, “it was my sock. My sock. When I was in prison, they’d only give you a few socks, and those were your socks, and you had to look after them. We get so attached to these little things that belong to us in there, like those cheap socks, that they become so much more important than what they are. I have to re-learn that a sock is just a sock.” Bozella also has to come to terms with the fact that he’s missed large pieces of the lives of people he cares about.

Firsenbaum sees a bumpy road ahead, but he’s hopeful. “Money’s a serious problem for Dewey right now. He’s trying as hard as he can, but he hasn’t been able to find a job. He needs someone to look past the fact that he’s been in prison for 26 years and look at the educated, dedicated and caring person in front of them.”

Bozella speaks often about his dream of becoming an actor or a director. Failing that, he wants to use his experiences to help others. “Dewey wants to work with kids who have the same choice he had,” Firsenbaum says. “The choice to turn to either the streets or to education. He can help these kids; he can give them real advice. The problem is, and it’s very ironic, that it’s very difficult for someone who has been in prison to be allowed to work with kids that are struggling with the same issues.”

Bozella, though, knows better than to see his past as an ending to his future. Now, on the other side, he knows how to trump his demons. “I used to think the world owed me something,” he says. “That’s not it at all. I owe the world something. I’ll get there. Life is a challenge. There’s struggle and conflict. It’s what you do with that struggle and conflict that matters.”

Rebecca Binder is a litigation associate at the Boston law firm D’Ambrosio LLP, where she practices commercial and real estate litigation. She is also president of her Amherst class. This is her fourth feature for Amherst magazine.

Boxing photo by Dan Cronin / New York Daily News; courtroom photo by Lee Ferris / Poughkeepsie Journal; umbrella photo by G. Paul Burnett / New York Times