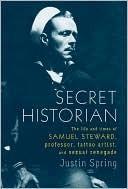

An Excerpt from Secret Historian by Justin Spring '84

|

1. “Wild—Hog Wild”

Samuel Morris Steward was born July 23, 1909, in Woodsfield, the seat of Monroe County in southeastern Ohio, a county bordering on Appalachia, and in many ways just as impoverished as that region. His modest, small-town beginnings are important to an understanding of the man he later became, for his plainspoken humor and openness to all things sexual are surely related to his country roots. At the same time, his lifelong preoccupation with the nature of his homosexuality can be seen as a direct response to the “stern and austere Puritanism of my Methodist maiden aunts.”

Outside accounts of Steward’s early life are basically nonexistent, and he himself wrote of it only in passing; those few sentimental memories he retained of his childhood—whether shared in letters to his sister, or else recounted in his journals or unpublished memoirs—seem to have made him too sad to dwell on it for long. And indeed he had a painful early life. His academically brilliant mother had died of an intestinal obstruction when he was only six, and his father, who had both drug and alcohol addictions, was essentially unable to care for either Steward or his baby sister. As a result, Steward grew up in a boardinghouse run by his mother’s sister and two stepsisters. These three older spinsters—Elizabeth Rose and Minnie Rose, and their half sister Amy Morris—spent most of their day “cooking and serving, making beds and washing, and hoeing in the garden behind the house when there was time for it.”

The Morris, Rose, and Steward families had resided in the Woods-field area for generations, and were well established in the professional class; even Steward’s father, despite his drinking and drug problems, had served for a time as Monroe County’s deputy auditor, and despite his multiple addictions taught a weekly Methodist Bible class for more than twenty years. Steward’s paternal grandfather, meanwhile, was a respected country doctor. All of Steward’s family on his deceased mother’s side were teetotalers as well as devout Methodists, and the church literally loomed large in their lives, for the town’s imposing redbrick church stood just across the street from the boardinghouse. The town had no Catholics, and the one black who had attempted to settle there had been run out of town on a rail. As a result, Steward grew up seeing the world as basically divided between those who devoted their lives to Protestant churchgoing and Christian good works (such as his aunts and maternal grandparents), and those who had, for whatever reason, fallen away.

Faced both with the death of his mother and the improvidential absence of his father, the six-year-old Steward might well have withdrawn into grief or shocked stupor. But with the resilience of a child, he did just the opposite, dedicating himself energetically to becoming a highly sympathetic companion to the work-worn aunts who had taken him in. By stepping away from his own feelings and concerning himself primarily with the management and care of others, he was insuring he would not once again be discarded, and in so doing he was also setting the pattern for his later life. But as a result he also grew up feeling very much an outsider, and relatively at a distance from his own feelings and impulses, for he naturally had a great deal of grief and sadness about his own life situation. His aunts seemed not to notice, however, for they had any number of problems and concerns of their own, and moreover they themselves were not very happy people. Worn down by endless amounts of domestic work and by constant money worries, they seem to have lavished most of the joy and attention they had on Steward’s very beautiful baby sister. Steward was after all a boy, and seemed relatively capable of taking care of himself. None of the three aunts had much understanding of males: after all, none of them had married or had children or even had brothers. As adult women living in a home owned by aged parents, their own lives were, in a very real sense, a surrender to womanly duty: their personal frustrations and domestic claustrophobia were something they accepted as their lot. These were the three adults who populated Steward’s childhood—stern, comfortless, deeply religious women who could not quite understand him or his ways, and yet whom he felt an urgent, almost desperate need to comfort, accommodate, and appease.

Out of the double loss of his mother and father—one loss permanent and abrupt, the other ongoing and perpetually inconclusive—Steward seems to have accepted from a very early moment that his life’s essential condition would be one of loneliness and exclusion. Deprived of parental love and recognition, he would grow up expecting very little love from others. Likewise, having experienced very little touching, warmth, or affection as a child, he would eventually find that prolonged physical intimacy made him extremely uncomfortable, and that those who expected the same from him were destined for disappointment. He would grow up to be a very sociable man, highly skilled at managing and seducing others, but unable to cope with everyday closeness. As a boy, he did his best to fit in, but at the same time he spent a good deal of time by himself. His preference for solitude eventually led this gifted young boy to develop a rich private fantasy life, one in which he thought of himself as someone special, separate, and apart.

Steward was very intelligent, like his mother, and he worked very hard in school. His aunts had high expectations for him, for although they were stuck in the boardinghouse, they wanted something better for him, and also for his sister. They saw to it that he earned top grades, kept fastidiously clean, had perfect manners, and in general did everything right. Wanting so much to please and amuse his aunts, Steward not only worked hard at his studies but also quickly mastered the piano, and soon specialized in “showy little pieces” that he picked out specifically to delight them. They, in turn, made a great fuss about his looks, which were delicate and refined. In an early set of photographs, he is beautifully turned out in a Little Lord Fauntleroy suit featuring velvet breeches, a matching jacket, and a delicate round white collar. In many ways, he seemed like a perfect little doll.

Whatever ambivalence Steward may have felt about his childhood in later life, he never denied the goodness of his aunts, or their love of him, or the many great sacrifices they made on his behalf. And, in fact, he would portray them quite tenderly in his first literary novel. But he was also exhausted by them—for the perfect, doll-like, self-contained little man they so much wanted him to be was very far from the complicated, fallible, and emotionally deprived young boy that he was, or the troubled teen he eventually became.

Because of his extraordinary academic achievements, Steward seems to have felt from a very early moment that the great awareness of “difference” he had from the people around him was primarily due to his intelligence. And indeed he was very intelligent: brilliant not only at all his school subjects, but also at music, amateur dramatics, and drawing. Among these many activities, though, he found his greatest pleasure in reading and writing, for through them he began to imagine himself in the outside world. From his earliest days Steward read everything he could lay his hands on: popular fiction, poetry, and the great classics of Western literature. He borrowed vast numbers of books from the local library, and also purchased books and magazines by mail. Because silent films were shown weekly in town, Steward became a great fan of film and stage celebrities—men and women whose lives and careers seemed so real to him in the pages of Photoplay that he began to write them letters. Much to his amazement, several wrote back. In this way, reading and writing served from earliest childhood to create for Steward an intimate conduit to the world of his dreams and fantasies—a world full of glamorous and fascinating people so very different from the simple folk of Woodsfield. Before long Steward was writing to nearly every celebrity he could think of—authors, musicians, and film stars—and assiduously collecting and cataloging their autographs and letters. He cherished their responses to him as proof positive of his own special ness. Through his collection of celebrity letters and autographs, he had created a world in which he stood at the absolute center.

In his unpublished memoirs, Steward makes clear that while he spent many of his leisure hours reading and writing and chasing down autographs, he also spent a good deal of time playing with other boys and girls. He may have been thought of by his contemporaries as “different” because of his bookishness, but he was always treated with respect. The facility with which he handled nearly everyone around him—from his aunts to his teachers to his fellow high school students—suggests that Steward had a talent for communication. He was by no means a leader, but by the time he reached high school (and the emotional and physical changes that come with the onset of puberty), he was well known for playing any number of sly pranks and practical jokes. Duplicity was something in which, for whatever reason, he took an enormous and childlike delight: being bad, misbehaving, and “crossing the line” between acceptable and unacceptable behavior were in many ways central to his character from boyhood onward. This love of duplicity became even stronger when Steward discovered sex.

Growing up under the watchful eyes of spinsters, Steward had known that sex was “wrong” long before he knew what it was. He later remembered, only half jokingly, that “in my sheltered little-boy Methodist way, the talk [of sex] caused me much agony. The slightest brushing of my hand against my penis was not only a religious sin, but would lead to blindness and pimples, kidney disease, bed-wetting, stooped shoulders, insomnia, weight loss, fatigue, stomach trouble, impotence, genital cancer, and ulcers.” In fact, he so deeply internalized his aunts’ great fear of sexual “filth” that the unintentional discovery that his foreskin could retract (and the sudden sight of his filth-encrusted glans) shocked him so deeply that he passed out cold.

Not surprisingly, then, Steward experienced a series of significant physical and emotional upsets as his body entered puberty. Sexual thoughts and desires began to surface within him despite his best efforts to exclude them from consciousness. It was at roughly this time that he began to engage in various forms of aggression and bad behavior, including pranks and practical jokes. As a result, he wrote, “The meek mild little mama’s boy, the potential sissy, may have remained that on the outside, but inside there was a curious change to a twelve-year-old devil.”

He began to do a lot of spying and eavesdropping. Steward’s growing curiosity about other people’s private lives and personal habits presumably led him first to peep through the many keyholes available to him in his aunts’ boardinghouse. There he could watch and listen to whatever the various male lodgers might be getting up to in their rooms. He also began to spy on various other people throughout Woodsfield, including a girl who lived next door. In one of his earliest surviving short stories, written while still a preadolescent, Steward describes spying on a teenage boy and girl who have gone skinny-dipping together; while he senses something momentous is about to happen between them, he does not yet know what it is.

Steward’s first introduction to sexual self-pleasure came about through instruction by another boy in the practice of masturbation. He achieved orgasm some time later, in private. Some time after this first orgasm, Steward began to realize that he was sexually excited by other boys. While he found the realization troubling, he also seems to have realized in short order that he could do nothing about it—just as, indeed, he could do nothing to control his interest in sex. As he later observed, “‘Choice’ had no part in [my sexual identity.] When I discovered what I wanted [sexually], every corpuscle, every instinct I had, drove me unerringly in that direction.”

Steward later wrote that he could recall no real concern among the adult population of Woodsfield about the sex games he and the other boys in town sometimes played, at least insofar as these games might potentially cause them to develop into homosexuals. He credited this lack of concern to a simple, widespread disinclination to discuss sexuality in general, and on top of that, an almost complete, culture-wide ignorance about the existence of homosexuality:

Midwest American views on homosexuality in the 1920s were very quaint, and were based on the assumption that all people raised in civilized Christian countries knew better than to fall in love with, or bed, persons of the same sex. Knowing better, then, the Fundamentalist mind made two breathtaking leaps of illogic: people did not do such things, and therefore such things must be nonexistent. This kind of thinking protected us all during the 1920s and 30s. Though one might be teased for being a sissy, no one could believe that any person actually engaged in the “abominable sin.” We lived under the shadow and cover of such naiveté.

Thus while Steward recalled many injunctions against “sin” in his religious upbringing—both in church and at home—he recalled no specific early injunctions against homosexuality. Through his own investigations, however, Steward soon ascertained that sexual acts between men were not only strictly illegal in Ohio, but also punishable by incarceration. In his unpublished memoirs, he concludes the story of his first non masturbatory sexual experience with another boy—“a big guy” football player who had convinced him to engage in an act of oral sex that was “over in less than two minutes”—by going on to note that the punishment for such activities in Ohio at that moment so far exceeded the “crime” as to make the whole situation absurd: “So began my criminal life, then punishable by the laws of the state of Ohio—at that time—by about twenty years of imprisonment, I guess. Each time. Total incarceration in Ohio: between five and six thousand years.”

Steward had enjoyed the encounter with the football player, and as a result, he subsequently provoked similar encounters with other (usually older, better developed) boys in locations all over Woodsfield: in the town graveyard, in a neighbor’s attic, in the courthouse bell tower, and even in the same room at the Methodist church where his father taught his Sunday Bible class. Since Steward usually proposed and intiated these activities, he felt no sense of coercion by the older boys. Rather, he considered himself unique:

I figgered I was put in that town just to bring pleasure to the guys I admired . . . In that small (about 350 students) high school, the word got around quickly enough, and (I think) they all came to look on me as . . . a dandy substitute for their girls . . . I felt different from those boys—superior in a way, because I could give them something they wanted (and needed?) . . . I thought I was the only one, and grew somewhat proud that I could satisfy these boys, most of whom I looked up to and admired because they were my adolescent “heroes.” [And] they [in turn] treated me with a funny kind of respect, as if they knew that if they made me mad, they wouldn’t get any more . . . I was not patronized or made fun of. In those far-gone days, everything seemed “natural.”

Even so, these new activities made Steward ever more clearly an outsider. To his teachers and his aunts he may well have seemed a handsome young man of great academic promise, but to himself—and among the boys with whom he was active—he was not only a rebel (a boy who stole from the cash register in his uncle’s store, got drunk on stolen wine, and once even threw a pumpkin through the window of the high school principal’s house), but also an oddity (because he was a boy who enjoyed pleasuring other boys sexually, and seemed to have no shame about doing so). To Steward, who had basically already accepted that he would never quite “fit in,” his sexual activities were just another aspect of his teenage rebellion. With puberty, he later observed, “the birth of desire had taken place in me, and the patterns that I needed to survive were firmly imprinted by the time I left the town [of Woodsfield]: concealment and pretense, duplicity, a guise of wide-eyed innocence—and a kind of ‘passive aggression’ [unusual] in such a shy-seeming young man.”

Of course, Steward was hardly alone in adopting such a strategy; most homosexual young men of his generation found themselves facing a similar crisis of disconnection from the society around them as they became sexually active. Just as the orphaned and rejected Jean Genet (Steward’s exact contemporary) would note that through homosexuality, violent crime, and thievery he had “resolutely rejected a world which had rejected me,” Steward took a similar view of his departure from the upstanding life into which he had been born, and toward which his aunts had so earnestly propelled him:

The personality which has been kept repressed, as mine had been by the strict Methodist upbringing my aunts had given me, and kept within the strictest lines and boundaries, really goes wild—hog wild—when it finally breaks away. And although I was still living within the family walls, the rebellious spirit was growing daily stronger . . . I had to be free.

Steward’s ability to think clearly and without too much anxiety or self-blame about his sexual activities (or at least to view them with a certain degree of humorous detachment, and to recognize them not as aberrant behaviors, but rather as aspects of an essential self that absolutely had to find expression) is something he later credited to an extraordinary boyhood find: a copy of Havelock Ellis’s Studies in the Psychology of Sex, Volume II: Sexual Inversion. Steward had serendipitiously discovered the book under a bed in the boardinghouse, where a traveling salesman, after stealing it from the “restricted” section of an Ohio library, had subsequently left it behind.

A voracious reader even in his early teens, Steward had already special-ordered Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle and The Interpretation of Dreams through the Woodsfield confectioner by the time he found the Ellis volume. But the latter book was a unique godsend, for this landmark of early-twentieth-century sex research was particularly sympathetic toward “sexual inverts” and “sexual inversion”—that is, to homosexuals and to homosexuality. The book immediately set Steward’s mind at ease about just who and what he was, and proved a welcome alternative to the vague but terrifying sermons he had heard all through childhood about “sexual sin.” Thanks to Ellis, “not only did I discover that I was not insane or alone in a world of heteros—but I [also] learned many new things to do. I made a secret hiding place for the book under the attic stairs, and read and read and read. Thus I became an expert in the field of [sex] theory (by the time I finished the book I probably knew more about sex than anyone else in the county) and then began to make practical applications of this vast storehouse of material.”

Steward affects nonchalance about his sexual identity in his memoirs, and doubtless he was nonchalant about it for much of the time. But he also faced a very difficult moment of self-recognition in mid-adolescence, as he realized that what he was getting up to with other boys was simply not acceptable. The realization became manifest in an incident involving, of all people, his father.

Steward’s father had been largely absent throughout his childhood; during that time, Samuel Vernon Steward’s brief, rare visits to the boardinghouse were almost always painful ones, for his inability (or unwillingness) to provide for his children had complicated the lives of Steward’s aunts considerably, and they resented him. They also resented his involvement with other women, since they felt he ought to have remained faithful to the memory of their sister. His ongoing dependence on drugs and alcohol, meanwhile, had led him to ignore both the emotional and the financial needs of his children.

The son of a country doctor, he had dabbled with drugs since boyhood. He had obtained virtually unlimited access to drugs as a young adult by securing a pharmacist’s license through the study of pharmacy in college. His subsequent experiments had led him to become a frequently relapsing opium addict* who also “dabbled largely in [other] drugs, especially laudanum and morphine.” Though in many ways a weak man, he was capable of unexpected violence; one of Steward’s few early childhood memories was of watching his father hit his mother hard across the face, merely for having dropped and broken his bottle of ketchup.

In later life, Steward kept no photographs of his father, only a couple of inconsequential letters and a small book of occasional speeches. The contents of these documents suggest he was a man inclined to sanctimony. The fact that he went on to spend twenty years teaching a Sunday Bible class at the church across the street from the boardinghouse where his children were growing up without his financial support suggests that there was much about him that Steward might justifiably have disliked.

According to Steward, his relationship with his father worsened after the two were tested for their IQ:

The propagandizing of my aunts against whomever [my father] looked upon as a possible new bride had affected me; they somehow felt that he should remain true all his life to the memory of my mother [and so did I]. An additional strain was that I had earned my own way during the high school years, since with his meager salary he could not support either myself or my sister. And finally, the superintendent of schools had given both my father and myself the same IQ test—which had just then been invented. When the weighting of the scores was adjusted for our ages, it was discovered that my result topped his. I do not believe he ever forgave me, and was jealous of that small detail the rest of his life; he often referred to it, but never in my hearing.

The final break between father and son came after. Steward wrote a sexually suggestive note to a handsome young traveling salesman at the boardinghouse, and the salesman, outraged, subsequently gave the note to the proprietor of the town’s only restaurant, thereby making the proposition—and the proof of it—town-wide public knowledge. Publicly shamed by his son, Samuel Vernon Steward drove the boy out to the countryside to discuss the matter in the privacy of his car. There, as Steward later recalled, his father had bawled him out:

“I want to know what the hell a son of mine is doing writing love letters to another man.”

“I think,” I said, drawing on my new vocabulary from Have-lock Ellis, “that I am homosexual.”

“. . . Don’t give me any of your smart aleck high school rhetoric!” He bellowed . . . [And] that was the way the conversation went on for about a half hour. When I saw that he wanted to believe that I had not actually sinned, the game became fairly easy . . . I pretended to be chastened, to be horror-struck at the enormity of [what I had proposed to the salesman] . . . I worked it to the hilt, falling in easily with his suggestion that perhaps I should go to see a professional whore—that such an experience might start me on a heterosexual (he said “normal”) path.

Excerpted from Secret Historian by Justin Spring.

Copyright © 2010 by Justin Spring.

Published in 2010 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.