Vacation in Absentia

By Rand Richards Cooper ’80

|

Let me say right off: I’m no Luddite. I gladly use On Demand; I download songs; while working at my keyboard, I frequently go online to pursue some useful bit of knowledge—or to play a game of chess. I’m connected, in other words. Yet the seemingly universal desire to be connected everywhere, all the time, leaves me baffled.

Last August we vacationed with friends in a house on Cape Cod, and on the first day, I dove in the water with my cell phone in my pocket. Oops! Spending the week as the only deviceless adult left me curiously out of sync with the others. For instance: We’re sitting in the living room, four Red Sox fans watching baseball. Well, I’m watching. The other three are busy with their handhelds. Jon checks in with work, Dan Sr. catches up on email, and Dan Jr. chases down Red Sox trivia questions. Who hit the homer that tied Game 6 of the ’75 Series? (Bernie Carbo.) Is Tim Wakefield really both the winningest and the losingest active pitcher in baseball? (Yes.) Bit by bit our conversation becomes a sports quiz show, as the actual game goes on, semi-watched.

I was bemused to note that our devices were diverting us from our diversions. I also couldn’t help thinking that iPhone immersion was changing Dan Jr. He’s a thoughtful, convivial guy, but his iPhone seemed to bring out a side of him that was more impulsive and way more geared to competitive quizzing. It also made him, simply, not quite there.

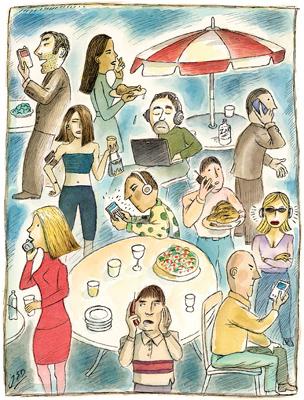

Here’s the America I see these days: People everywhere with their heads bent, oddly as if in prayer, their fingertips flicking at their screens. A couple sitting in a restaurant, both silently flicking. A woman, walking her dog and flicking nonstop, oblivious to the fall day. Recently I attended a political forum, and the mayor of Hartford, Conn., was sitting next to me in the audience. The whole time, he consulted the iPhone in his lap. I understand that: You’re mayor of an American city; someone always wants a piece of you, and you have to give it up. But who, other than a politician, would want that kind of life?

Most people, apparently. We are now all mayors, ruling over our virtual municipalities, compulsively checking in, checking back, giving up pieces of ourselves. We’re not only connected, we’re beholden. We worry that something might be happening without us. But what, and where? The virtual municipality brings to mind Gertrude Stein’s famous dismissal of Oakland, Calif.: “There’s no there there.” Yet this digital nowhere is where we keep trying to be. Meanwhile, our here is evanescing, right in front of us.

On the Cape Cod trip my wife and I had our 5-year-old daughter with us, and Dan Jr. and his wife had their kids, aged 6 and 8. The three children got along beautifully. Watching them play, I noted how completely absorbed they were in the world of the back deck and the yard, and in each other. They existed fully in the moment. I found myself wondering: Isn’t it enough to take in the particularities of the late-summer light, the breeze, the game the children are inventing and the way their gleeful shouts evoke an afternoon of your childhood 40 years ago? Being present in the moment is what affords us, to borrow a term from Henry James, “a personal and direct impression of life.”

Technology is a majestic human story, and the benefits we’ve gotten from farming out our tasks to machines are incalculable. Yet with those tasks go the abilities to do them. What happens when what we’re farming out is consciousness itself—the ability to be ourselves, with ourselves and with one another? How do you go on vacation when your daily life increasingly centers on an act (and means) of vacating? I recently asked my wife, Molly, what a new communications technology would have to do in order for her to buy it. Her answer: “It would have to increase the amount of face-to-face human contact in my life—away from a screen.”

One evening in the shadow-dappled backyard of our rented house on the Cape, there occurred an eerie moment. As our kids romped, we parents gathered around a stippled-glass patio table. Picture five adults laying phones and iPads on the table like six-shooters around a saloon poker game. We start a conversation, but mere minutes into it the table begins to vibrate. The weird call from the Ouija board and the alacrity with which everyone glances down to check, Is it mine?, sum up for me the mystery of life today, with its extravagant busy-ness. Who is speaking to us, who is summoning us away from ourselves to such urgent duty in the invisible beyond?

Cooper, a novelist and essayist, is a frequent contributor to Amherst magazine.

Image © 2012 John Dykes c/o theispot.com