Reviewed by Robert E. Weir

Photos from the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library

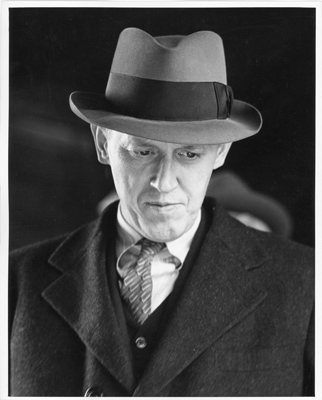

[Biography] December 1943, Tehran, Iran. The Allies have just agreed to invade France in the spring. The official photo placed a confident U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the middle, with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin ramrod straight on his right and Britain’s Winston Churchill glumly on the left, looking away from the camera. After two years of opposing a third front, Churchill had finally capitulated. The man who convinced him is missing from the picture: FDR adviser Harry Hopkins.

Give David Roll credit for moxie. His fascinating new biography, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler (Oxford University Press) joins at least six other scholarly works, including Robert E. Sherwood’s 1948 Pulitzer Prize-winning Roosevelt and Hopkins. Roll’s contribution is his focus on World War II; the “touch” in his title refers to Hopkins’ ability to mediate the monumental egos within the Allied leadership.

Thoughts of World War II invariably conjure images of battlefield valor and military strategy, with political conferences an afterthought. Roll reverses the gaze to make us see the cat-and-mouse diplomacy that dictated how the war was fought. What did Roosevelt, Churchill, Stalin, China’s Chiang Kai-shek and Free French leaders Jean-François Darlan and Charles de Gaulle have in common? Aside from mutual dislike, not much. FDR loathed de Gaulle and tired of Churchill, whom he saw as a booze-soaked self-aggrandizer. Roosevelt needed an intermediary and found one in Hopkins. Everyone, it seems, liked Harry, who became, among other things, FDR’s unofficial ambassador to Churchill.

Historian Warren F. Kimball likened Roosevelt’s wartime diplomacy to that of a “juggler,” but Roll thinks it was Hopkins who kept the balls in the air. Critics called Hopkins a “Rasputin,” but that’s reductionist; Hopkins was Roosevelt’s confidant, friend, sounding board, muse, diplomat and fixer. He even lived in the White House.

Hopkins battled Congress to secure the controversial 1941 Lend-Lease Act; made sure war matériel got to Britain, the Soviet Union and China; and sacrificed his health in endless shuttle diplomatic missions. Roll reminds us how grueling cross-Atlantic diplomacy was in the era when a meeting with Stalin meant several days of rigorous travel and more than 25 hours of flight time.

Hopkins isn’t an official casualty of World War II, but he literally gave his life for his country. He battled stomach cancer starting in 1931. The treatments left his body unable to absorb nutrients, and he required numerous hospitalizations before, during and after missions. He ignored doctors, did what his country asked of him and was just 55 when he died in 1946.

Roll mines some new sources on Hopkins: KGB files, as well as new documents concerning leaders with whom Hopkins met. Roll also interviewed Hopkins’ relatives, though little in the book will startle specialists. The book’s biggest revelation is Roll’s demolition of the spurious charge unleashed by anti-FDR conservatives that Hopkins was a Soviet agent. KGB files prove its falsehood.

But whether one is a specialist or a general reader, Roll’s attention to detail will fascinate. He gives a warts-and-all portrait of world policymakers, compete with hard drinking, womanizing, ribald humor and prickly egos. We learn that the only thing worse than eating White House food was drinking one of Roosevelt’s cocktails. More substantively, we see that World War II was fought as much in smoke-filled conference rooms as upon smoke-filled beachheads.

The book also dismantles the “betrayal”-at-Potsdam myth advanced by postwar anticommunist zealots. Roll notes that the Allied delay in opening a front in France in 1942 cut the Soviets adrift and guaranteed that, if the USSR survived, the West would be in no position to dictate terms to Stalin. Another dimension of the myth holds that, with FDR dead and Churchill out of office, Stalin had his way with neophytes Harry Truman and Clement Attlee. That story overlooks the Potsdam presence of the war’s most experienced negotiator: arm-twister Harry Hopkins.

Weir is a visiting professor of history at UMass.