A sculpture inspired by Russian history will be installed at the Library of Congress.

By Rachel Rogol

[Sculpture] A free press was not exactly a priority for the Soviet Union. “Under Stalin, anyone caught with Cyrillic type was shot for treason,” says Lloyd Schermer ’50. “Those who had wood type used it to keep warm in the winter.”

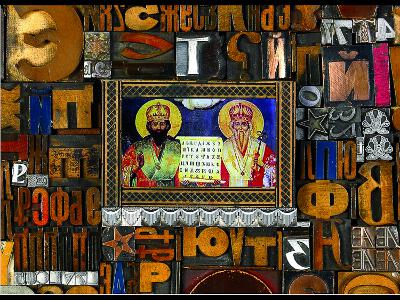

Schermer has found a better use for it. He’s taken antique Cyrillic wood type—the kind used for centuries in ink printing—and used it to make a sculpture that will hang in the Library of Congress.

Titled Live!, it is one of dozens of Schermer’s type sculptures. These works hang in galleries and offices ranging from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, to The New York Times, to Amherst’s Frost Library.

Live! is a tribute to the Cyrillic alphabet. It takes its shape from the first letter of the Russian word , which means “to live.”

“It’s one of those uniquely beautiful and graceful Cyrillic letters invented to symbolize the Slavic sound,” Schermer says. He made the sculpture out of 700 pieces of antique Cyrillic type—the rarest script in his extensive collection of more than 20,000 pounds of letterpress type.

A retired newspaper publisher, Schermer creates art out of the materials that surrounded him during his publishing career. Letterpress type was used in printing for centuries, until technological advances in the 1950s made it obsolete.

At that time, Schermer says, “most of that beautiful type was hauled to a dump.” Large collections are now hard to come by.

Cyrillic type, perhaps because of Stalin’s aversion to it, is especially scarce. When Schermer became interested in finding it, he first worked with a museum in St. Petersburg to search publishing houses throughout Russia. That effort proved fruitless. Eventually he found a bankrupt Ukrainian newspaper in Canada that happily sold him what they had.

All of the type in Schermer’s collection is hand-carved and made of maple, beech, birch, ma- hogany, ebony, cherry or walnut. The letters are so full of ink that every side of every letter needs to be sanded down to the raw wood. After sanding, Schermer cleans each piece to allow the natural patina of the wood to show through. Then he applies a layer of conser- vator’s wax.

The Library of Congress does not often accept art or artifacts as donations. It made an exception for Schermer’s sculpture. Grant Harris, head of the library’s European Reading Room, where the sculpture will be installed, hopes to plan an event in conjunction with its display, featuring a scholar of Slavic languages.

Rachel Rogol covers the arts for the Amherst Office of Communications.