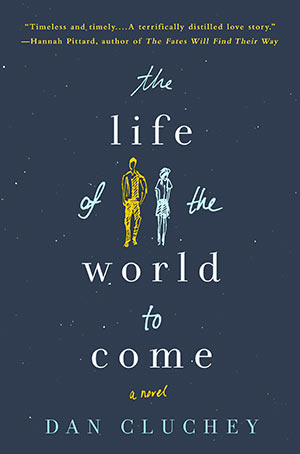

Dan Cluchey ’08 has written speeches for Eric Holder, Kathleen Sebelius and other senior members of the Obama administration. Now the Harvard Law graduate has published a novel, The Life of the World to Come (St. Martin’s). It examines responsibility and loss through the eyes of a young lawyer trying to save the life of a man on death row while also struggling with the departure of the woman he thought was the love of his life.

2016: Summer Interview: Not a Great Love Story

What sparked this project for you?

The first bits that I wrote down were the final pages, which borrowed from some raw, awful writing I had done in David Sofield’s “Writing Poetry” course at Amherst—a handful of syrupy phrases, words and ideas that had somehow gotten stuck either in my mind or on my hard drive. My process was to work backward from that thousand-word fever-dream ending, building out a story that could realistically wind up at that place. One of my favorite poems is “This Solitude of Cataracts”by Wallace Stevens. I decided that the entire point of the novel would be to try to make me (and, later, others) feel the way I felt when I first read that poem. My main character, Leo, encounters the poem late in the story, but absent that, I doubt anyone would make the connection explicitly.

Is your novel a love story? It’s invested in the idea of love but takes a hard departure from any familiar structure.

It’s a story that contains some love—that’s as far as I’d go. If you had a friend who said “I’m interested in reading a great love story,” and you suggested this book, how upset would your friend be with you after reading it? My guess is that she or he would be pretty furious, to the point of maybe not even texting for a while.

Is there any similarity between writing a novel and creating a convincing narrative about a legal case, e.g., for a jury?

Most of the same elements are going to be there: characters and conflict and conclusion and whatnot. A good lawyer, though, will successfully shut the door on any interpretation of events that diverges from the one she or he has presented, while a good novelist will often try to open doors of empathy and interpretation for readers to explore.

How did you find the creative energy to write a novel while also busy with the vicissitudes of law school and postgraduate life?

I wrote the first draft in the four-month window between taking the bar exam and starting my job with the Obama administration; for the most part, the story only had to compete for my time and energy with Breaking Bad and seeing how much Thai food I could eat in one sitting. A good deal of energy went into the editing process later on, so I had some experience with having to make time in my life to work on writing. It was always a break and never a chore, even as my life grew increasingly busy with all those damn vicissitudes.

How does writing a novel differ from writing a speech?

Every speech has a purpose it is trying to achieve; it may be to persuade, educate, inspire, mobilize, demonize, memorialize. Novels can seek those things, too, but a novel has the luxury of merely being an interesting story. There’s also an element of selfishness to authoring books. In speechwriting, you are required to write in a way that you believe will best reach your audience as they are, whereas there are plenty of novelists who sit down to write with only their own vision and perspective in mind. Speechwriting is a populist public service; novel-writing is whatever the author feels like.

Did I catch a secret allusion in the book to my favorite Amherst burrito place?

You did. But only because it was proving difficult to slip “hot cheese up front” anywhere into the text where it might be inconspicuous.