Photograph by Byba Sepit/Getty Images

NOTE: This article is adapted from an interview for the Amherst Reads book club. Listen to the full Q&A at amherst.edu/ magazine.

You were the first person I met on my first day at Amherst. I remember you, my father and me talking in the hallway in James.

Yes, in a corner. I remember that moment.

You were a hilarious math major with an enormous brain. I’d write essays, and you’d have pages of math scribbles. I thought that was great, because I came from a background of girls saying, “I’m bad at math.” And, by the way, I’m bad at math.

And, by the way, I know that at one point you were good at math. There is a real issue with girls and math, with our sense of what we’re good at and what we’re not. At Amherst, I decided I was bad at writing, because there were so many amazing writers around me, like you. I was intimidated. Math can be intimidating, too. I saw math, with its elegant forms, as mysterious, romantic.

You were the first to explain to me that math at a certain point becomes poetry.

It is a language, and like any language you have to learn it.

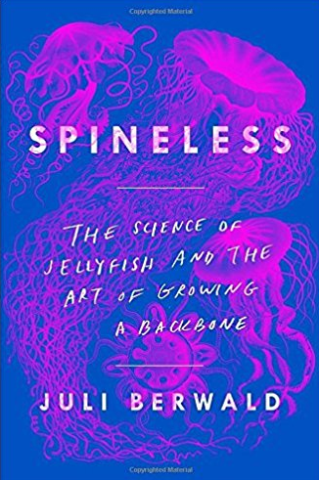

Spineless conveys the ways in which jellyfish are scientifically complicated. It also conveys the ways in which jellyfish are poetry. You seem to have an ear for communicating the universe’s grand mysteries.

“The universe’s grand mysteries”—that’s a lot, but I do love to take complicated science ideas and make them simple, or use metaphors to make them understandable. This is important, because science is going through a rough patch. People don’t believe in science anymore, which does not even make sense, because science is evidence-based; it’s not a belief system. If I can explain science in a way that is relatable, interesting and simple, then I’m doing a service. That’s especially true with the ocean, which is the focus of my book. Being terrestrial creatures, we tend to neglect it. The more I can connect what happens in the ocean to us as people on land, the better for our entire planet.

One of the hallmarks of growing up is being able to see things that are not you. Spineless follows an empathetic, accessible character—you—on a journey into another world, the ocean.

I remember, on one of our visits, talking about the fact that you didn’t know how the book would end, and how that was part of the journey. Even the fact of writing the book had its own adventure to it.

Once I made the decision to write a book, I knew I had to find an ending. And I knew I had to get out of my little office in the third bedroom of our house and go find it in the world.

When you got out there, what did you find? How do the jellyfish speak to you, and what did they say—about our oceans, about our future?

Translate for us.

They said that we need to pay closer attention to what we are doing to our planet, especially the oceans. A lot of the things we are doing to the oceans—warming them, acidifying them, overfishing them, building carelessly along coastlines—are making life better for jellyfish. In places where their abundances have increased, which turns out to be more than half the coastlines on the planet, jellyfish are a signal that ecosystems are damaged. It’s not hopeless: We could curb our CO2 emissions, which will improve warming and acidification. We could actually enforce fishing regulations. We could set up marine protected areas, which are like national parks on land. We could create biological barriers when we build canals between oceans that open up pathways for invasive species. But right now we don’t have the political will to do any of that.

The book takes us through the story of how you became braver, how you grew your spine. It also presents a parallel journey about civilization’s own spineless mess.

Right now, civilization is having a big party and not paying attention to its retirement plan. We are using up everything in our bank account, figuring someone else will take care of us once the money’s gone. The problem is that we have to take care of ourselves. In the book, I say we have to grow up. Unfortunately, I don’t see that happening right now. I’m less optimistic now about climate change than I was when I finished the book.

Your last chapter keeps wonder alive, when you say you have faith in us as a species. What’s changed in the year since you finished the book?

We dropped out of the Paris Accord. The new tax plan opened up the Arctic Refuge for drilling. And here in Texas, we had this crazy storm Harvey. The Gulf of Mexico was 4 degrees

Fahrenheit warmer than normal. Harvey passed over the Gulf, picked up a catastrophic amount of water and dumped it on Houston. My Facebook pages were filled with pleas from friends: “My house is flooding. It’s never flooded before.” “Please come rescue me.” “Please get the word out. I need rescue.” This is real, and it’s right now, not off in the future. I’m disheartened. That said, the ice caps haven’t melted yet. We could turn things around.

Who is the world leader in facing climate change? You’ve mentioned this to me before, and it’s always surprising.

I think it’s China. China’s leadership sees that renewable energy is the way of the future, and they want to be the ones to supply it. It’s the obvious future market. The future is not with fossil fuels. For us in the U.S., I am a huge fan of Carbon Fee and Dividend, which places a fee on carbon that’s redistributed to taxpayers on a per capita basis. Because it’s revenue-neutral it has advocates on both the conservative side and the liberal side—and I really think we need everyone together to solve the problem of climate change. There’s a great example of Carbon Fee and Dividend in British Columbia, where it’s been in use for about five years, and they’ve already drawn down their carbon footprint, and their economy is still doing fine.

Speaking of protected areas, I took 36 English classes in college. I clearly did not want to venture out into foreign waters. But I recall you were always more of an open-waters type, right?

In places where their abundances have increased, jellyfish are a signal.

To use the jellyfish metaphor, I slid around from subject to subject, building a schedule that I was curious about. It was more of a general education than a deep dive. But when I came back from Israel after studying abroad my junior year, I thought, “I should have been doing biology this whole time.” I came up with an independent study—a harebrained project that

Professor Paul Ewald in the biology department agreed to oversee. He was an evolutionary biologist, not an expert in the ocean, but I wanted to study coral biomechanics. I came up with this idea to do an experiment in a flow tank. I found out there was a flow tank underneath the floor of Pratt Gym, which was the geology building at that point. You had to crawl into the old swimming pool, which was underneath the floor. It was drained, and there were two flow tanks that nobody was using. I figured out how to get them working. I don’t know where I got coral skeletons. I injected dye into different parts of the skeletons and timed how long it took to wash out. It was a kooky experiment, and there were no results that came up. Zero, nothing. But it was great, because I did feel like I was doing real science.

In college, we all had the sense, in the best way, that we could do whatever we wanted. If you had something you wanted to pursue, there was nothing to stop you from pursuing it, which is a rare institutional approach.

The size of Amherst allows for that to happen. That, and the academic open mind.

Even considering the academic open mind, STEM in general does not have a reputation as being particularly feminist-friendly. Did you find yourself having to evolve to survive? And do you appreciate my Darwinian metaphor?

I very much appreciate your Darwinian metaphor. Yes, I did have experiences with STEM not being terrifically hospitable to women. At Amherst, I failed my comprehensive exam in math the first time I took it. I went to talk to a math professor about it, and he said, “Well, women math majors are always a problem. They always have trouble with these exams.” Which was a horrible thing to say and to hear. The good part was, I got enraged, studied hard and passed the second time. His comment acted as a motivating force. The math department was not a friendly place for women in the ’80s, or at least that was my perception. I’ve learned that at Amherst today, almost half of students who major in math or statistics are women, which is really encouraging. I looked through the math department faculty list before this interview, and there are a lot of women faculty now. We should applaud change when it goes in the right direction.

One great thing about jellyfish is that they are at once angelic and demonic.

What’s your take on the next generation, our future caretakers?

Compared to the people in charge right now, teenagers and young adults are much better at recognizing priorities. I’m hopeful that they can do a better job than we are doing. I just hope there’s enough material for them to work with.

Are you going to write the book to teach young people how to save the planet? Somebody needs to.

I’ve been thinking about writing a book called The Dead Zone, about all the dead zones in the ocean. These are places where there is not enough oxygen for animals to survive—because of both pollution and ocean warming. They have increased four-fold in volume in the last half century and are now the size of North America. But that seems kind of horrible.

One of the great things about jellyfish is that they are at once angelic and demonic. They’re a signal of an ecosystem that has been disrupted, that is out of whack. They’re toxic and have the ability to sting, and in some cases even to kill. But undeniably, they feel like our heartbeat when we watch them. They’re gorgeous. Their adaptations are phenomenal. They’re the most efficient swimmers; they taught us how all animals swim in the ocean. They can see and react to their environment in ways that are brilliant. I think we drift back and forth between these two places, and maybe one of the things we need to do is hold the demonic and angelic in our minds at the same time, together. Maybe that’s what I’ll write about going forward.

Margaret Stohl ’89 is the # 1 New York Times bestselling author of 11 novels for young adults, including Beautiful Creatures. She also writes the ongoing Mighty Captain Marvel comics and works in the game industry. Her first children’s novel, Cats vs. Robots #1: This Is War, co-written with her husband and illustrated by their child, arrives in September.