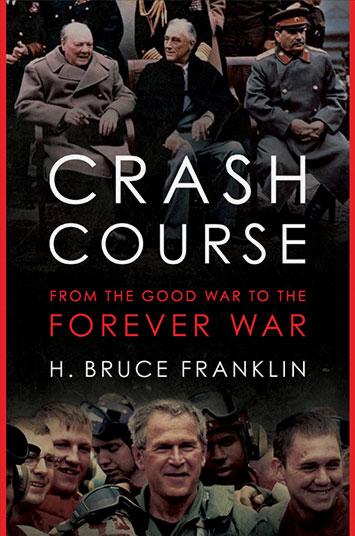

“I was born on a different planet.” That would be an arresting opening for a memoir, but it’s not the first line of Crash Course, H. Bruce Franklin ’55’s story of his inspiring life and dispiriting times. It’s a line he used on students at Rutgers.

“‘I was born on a different planet from everyone else in this room,’ I would announce at a crucial point in my course Science Fiction, Technology, and Society,” he writes. “Even people buried in their smartphones would emerge with curious or puzzled expressions. ‘ I was born on a planet where there was no known threat to the existence of our species,’ I explained. ‘None of you has ever lived on that planet.’ ... We Homo sapiens are so sapient, so intelligent, indeed so brilliant that we are the only species that has ever figured out a means to destroy our own species.”

That existential dread—which began when he was a 9-year-old Brooklyn boy—informs every page of Crash Course. A major American cultural historian, Franklin today is a troubled man. His worried mind ranges as widely as his scholarship has, across literary studies of Melville, science fiction as a mirror of American culture, prison writing as literature and the marine ecology of the lowly menhaden.

Years before he started reading, writing and teaching for a living, Franklin was working. Detailed with delight in these essays, young Franklin’s colorful career included stints in a mattress factory, a photo processing plant and Strategic Air Command (SAC). He comes by his criticisms of American political economy honestly.

“Episodic” seems a bit of a weasel word to describe a memoir. Any “Life and Times,” told honestly, resembles a series of anecdotes, and runs the risk of pointlessness. Franklin’s might seem a picaresque career for a scholar. But the dark truth that, at any minute now, the world could explode—that concentrates Franklin’s mind and narrative.

Ben Franklin wanted me to improve myself; Bruce Franklin wants me to think politically.

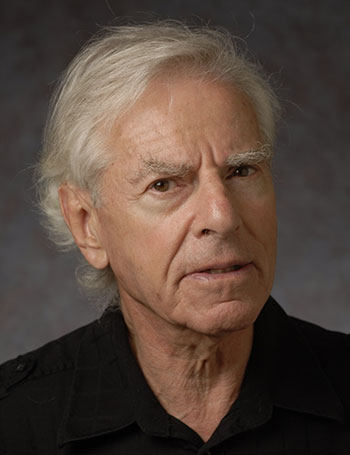

H. Bruce Franklin ’55

Two essays stand out. Franklin tells stories of his time on a tugboat in New York harbor in the 1950s, and aboard a nuclear-armed B-52 in SAC in the early ’60s. Crash Course careens from On the Waterfront to Dr. Strangelove, and as a memoirist, Franklin knows that Hollywood manufactured the memories many readers have of those days.

Filmmaker Elia Kazan got it wrong in the 1954 movie, Franklin writes. “The war on the New York waterfront was far more complex and insightful than that projected in On the Waterfront. … In reality, the longshoremen were fierce fighters for their own rights who saw the Waterfront Commission—which was primarily an agent of their employers and the anti-union governments of New York, New Jersey, and the United States—as their main and deadliest enemy.”

As to the on-screen idiocy and incompetence of mutually assured destruction seen in Dr. Strangelove, Stanley Kubrick got that right. Franklin recounts his terrifying experience at SAC: “The critics seemed to think that Dr. Strangelove was an over-the-top absurdist satire. I thought it was pretty realistic.”

Equally cinematic is Franklin’s radicalization about Vietnam. I was spellbound by his tale of being a young American in Paris in 1967 who starts hanging out with Vietnamese exiles and doubting the honesty of his own government.

That matter-of-fact storytelling is reminiscent of the first American memoir, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Like Benjamin’s, Bruce Franklin’s purpose here is to teach. Ben wanted me to improve myself; Bruce wants me to think politically. He admonishes us to improve the world.

Teaching and learning are often far from schooling. Franklin—recalling the Melville line that “a whale ship was my Yale College and my Harvard”—writes that at Amherst, “I learned in four years much less than I learned in two summers at Carb Manufacturing Company in Red Hook.” Before he went to grad school—mainly to get out of the Air Force—Franklin hesitated. “I was getting cold feet about going back to school after grade school, high school and four wasted years at Amherst.”

That’s the harshest description of the College you’ll ever read in this magazine. But the man has earned his opinion. Wasn’t there something in King Lear—the most worried mind in literature— something like: A waste it was not, so long as we can say, “This was a waste.”

Paul Statt ’78 is usually based in Philadelphia but is currently living in London, walking and writing a book about walking.