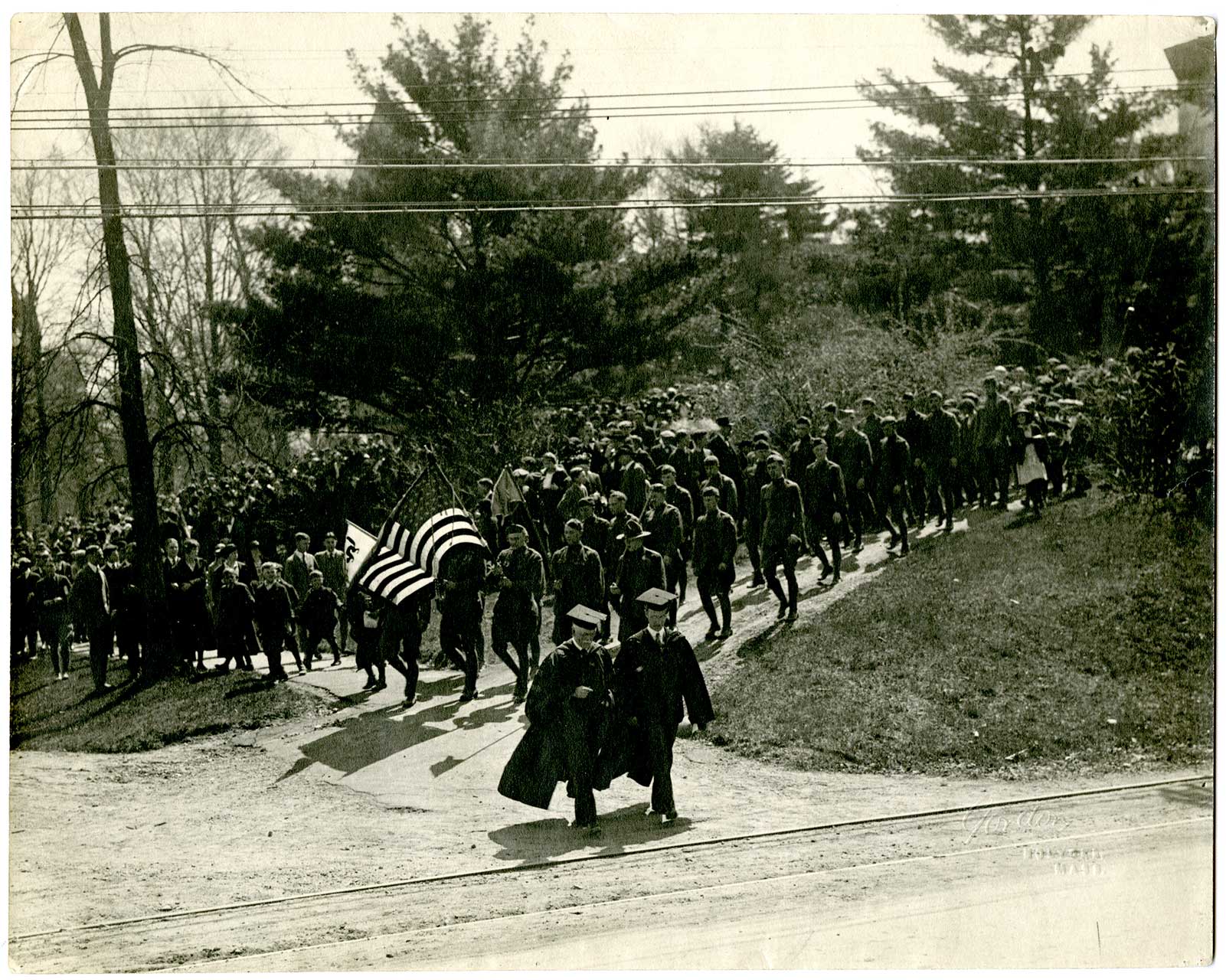

Amherst “Black Cats” Ambulance Unit and Amherst students, following President Alexander Meiklejohn and Dean George Olds to College Hall, April 1919

Two months later came the Victory Commencement of 1919, where a record 900 alumni returned to campus to hold regular reunions and attend events that commemorated Amherst’s contribution to the war. First came another unfurling of the giant Amherst Service Flag at the Alumni Council’s lawn ceremony honoring alumni, faculty and students who had served in the armed forces. At commencement exercises, the College granted B.A. degrees honoris causa—“for the sake of honor”—to students of three-year college standing who were said to have completed their education in the “school of war.” Dean George Olds then delivered a concluding address in which he lauded Amherst’s “Heroic Dead,” the 34 alumni and students “whose hearts had responded with angry beats to the call of the country’s danger, to the cry of an imperiled world-civilization.” A year later, the Heroic Dead were memorialized again by Frank L. Babbot Jr. ’13 with an $80,250 gift (equal to $981,152 today) that endowed the Amherst Memorial Fellows scholarships.

The Great War worked a second and more durable change in Amherst’s identity that lay visible just below the surface of most efforts to celebrate and memorialize its services as a “War College”: the remarkably increased presence of alumni in the College’s affairs, marked by the establishment of the Alumni Council in May 1914. Organized as eight standing committees—and with the ever-active prodding of its first secretary, Frederick S. Allis ’93—the Alumni Council pursued a broad range of activities that by war’s end would have alumni functioning as a corporate body and a determining force in defining the Amherst’s identity, publicizing its existence and securing its financial well-being.

Only two of many examples must suffice here. After the U.S. entered the war, it was the Alumni Council that created a War Records Committee, charged with the work of collecting and regularly updating information on Amherst men serving in the war and then publishing it in the Amherst Graduates’ Quarterly (established in 1911, and by then functioning as the Alumni Council’s official publication). The Alumni Council also assumed joint control of the Alumni Fund (established 1906) with the Board of Trustees, and in 1918 initiated what in time would become its most important purpose: annual and direct solicitation of gifts from alumni to help pay for Amherst’s operating costs.

IV.

By the time of the Victory Commencement of June 1919, the Alumni Council was functioning as a new administrative arm of the College, on its way to spearheading Amherst’s first major capital campaign—or, more precisely, Amherst’s first direct appeal to its alumni body as a whole to provide capital for planned new physical facilities as well as gifts to its endowment. The Alumni Council’s target was $3,000,000 to mark the Centennial of the College, scheduled for celebration at the 1921 Commencement.

Planning began in the office of trustee Dwight Morrow ’95 at J.P. Morgan & Co. in New York in autumn 1919. An all-alumni Executive Committee, chaired by Morrow, did the groundwork needed to organize a national campaign that was launched in College Hall in early November, with the now almost ever-present Morrow as the principal speaker. With the aid of local alumni fundraising committees—organized in close coordination with alumni associations across the country—solicitation of gifts began at campaign headquarters in New York in late November. It took just 10 days to raise $2,500,000. Alumni Council secretary Frederick Allis raised the other $500,000 by the time of the Centennial celebration. And when his work was done, he would report that $3,013,115 (or $41,160,834 today) in gifts and pledges had been raised, and that among Amherst’s then 4,913 living alumni, 4,044 (more than 80 percent) had pledged or given gifts.

At the Amherst Centennial, the Board of Trustees again turned to Dwight Morrow to make the formal announcement of the Centennial Gift. That decision did not make for a memorable speech. But putting Morrow center stage in June 1921 was in itself historically significant. Morrow, at age 48, had emerged as both agent and symbol of the new regime of alumni involvement in Amherst’s affairs. A driving force on the committee that created the Alumni Council, he also had served as president of the Alumni Association of New York, had chaired the Alumni Fund, and—after his appointment to the Board—had quickly established himself as the dominant voice on the Board’s Executive and Finance Committees, its two most powerful committees. He also had given generously to the endowment and solicited the $250,000 ($4,775,860 today) gift that had funded the design and construction of Converse Memorial Library in 1916 and 1917.

In his Centennial address, Morrow made no mention of his own service in the Great War. But doubtless most on hand knew that he had taken a leave of absence from his position as partner at J.P. Morgan & Co. in 1918 to serve first as appointed American representative to the Allied Maritime Transport Council (work that earned him the U.S. Army Distinguished Service Medal) and later as chief civilian aide to Gen. John J. Pershing.

Morrow also made no mention of how the Great War now deeply informed Amherst’s identity as what he called a “well-regulated family.” But evidence was not hard to come by. The names of the Amherst Heroic Dead were painted in gold letters atop the lobby walls in Converse. And when, in the early afternoon of June 21, more than 1,800 alumni and their families marched in a parade from the town commons to Pratt Field, it was not surprising to find almost all of the original contingent of the Black Cats—again flying their colors—making a triumphant return visit for the occasion. That night, the Black Cats found an even more prominent place in the Centennial celebrations during the “Amherst Milestones” Pageant, when they were invited to sit onstage during the last of 11 pantomime episodes which brought Amherst’s first 100 years to a close by portraying the College’s “supreme service in the War.” “Europe is agonized by the bloody torch of War,” reported the Amherst Graduates’ Quarterly, “and hearing her appeal, America draws the sword.”

V.

What would the later history of Amherst have been had the Great War never been fought?

It is, of course, impossible to know. But one can say several things about how the war changed Amherst.

To begin with, at no other time in its history had Amherst displayed a deeper sense of itself as a continuous institution than it did during the last 18 months of World War I and the several months following the armistice. Looking back, it’s also hard to imagine the remarkably quick success of the Centennial campaign in the absence of the new regime of alumni engagement for which the Great War had served as both background and occasion.

World War I also marked the emergence of Amherst graduates as a conspicuous and influential force in national affairs. Dwight Morrow and Harlan Fiske Stone ’94 were among several who gained national prominence as a result of war service. Even more prominent were Robert Lansing ’86, Secretary of State in 1916 and the most influential supporter of the Entente within Woodrow Wilson’s administration, and Frederick H. Gillett ’74, a congressman from Massachusetts (later Speaker of the House) who served on a joint subcommittee that had jurisdiction over nearly all congressional war appropriations.

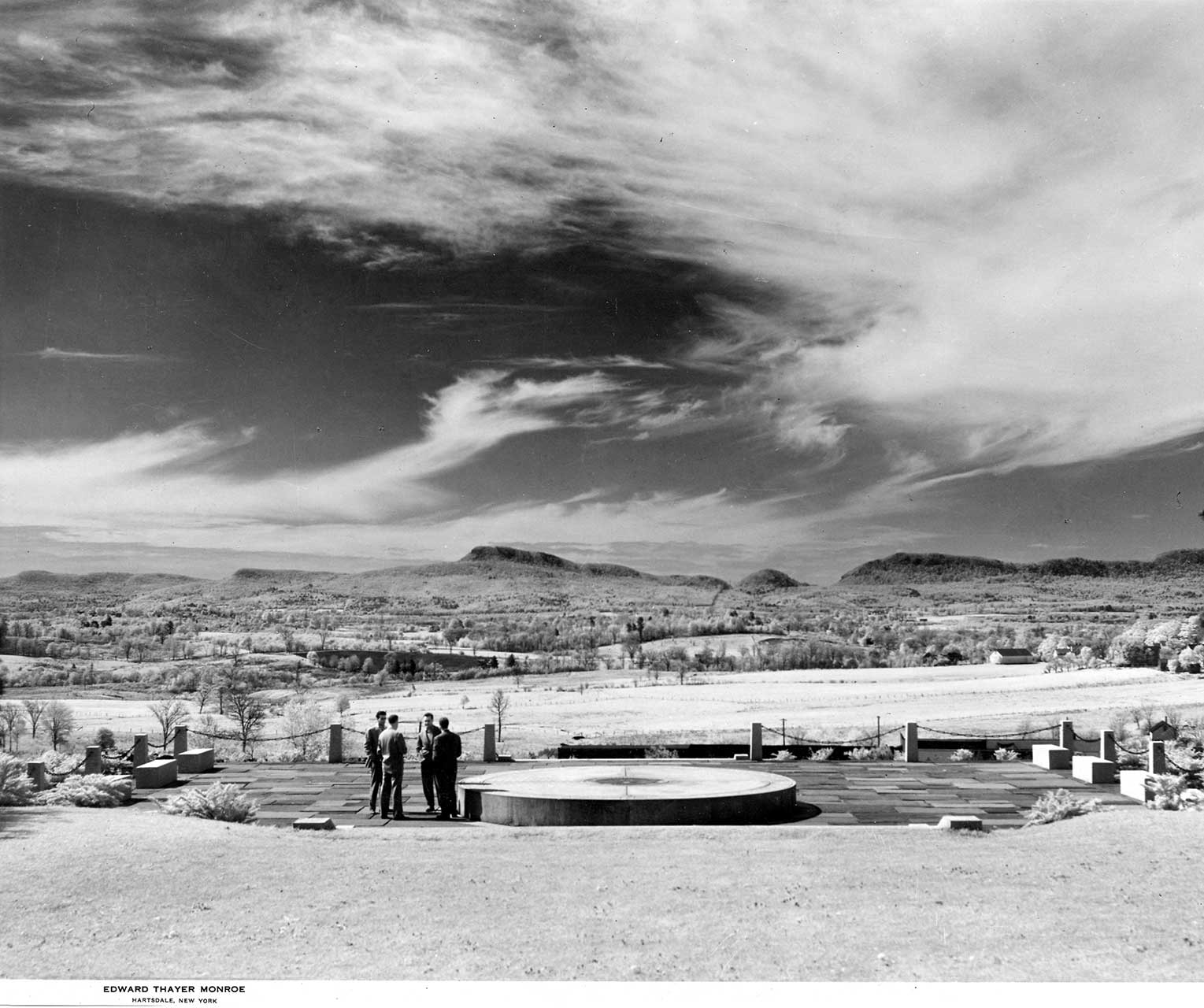

And finally, Amherst’s Heroic Dead have not faded from institutional memory. No longer painted on the lobby walls of Converse, their names—together with those of Amherst alumni and students killed in World War II—today are carved in stone on the War Memorial monument at the south end of the Main Quadrangle, looking out across Memorial Field onto the Holyoke Range. Since the monument’s dedication in 1946, perhaps no place on the Amherst campus has been more visited. And for those who stop and read the names, certainly no place more powerfully evokes the sense of Amherst as an institution that exists in time, defined by the accomplishments and the loyalty of successive generations of its graduates.

Amherst College War Memorial, 1946

Teichgraeber is a professor of history at Tulane University. He is the author of three books and numerous essays and reviews.