Theodore Baird, who taught four decades of Amherst College freshmen how to write, seldom published his own work, but he wrote every day in his journal.

It’s been more than a half-century since Baird’s English 1-2 composition course—which challenged, inspired and sometimes mystified students—went the way of other core requirements here.

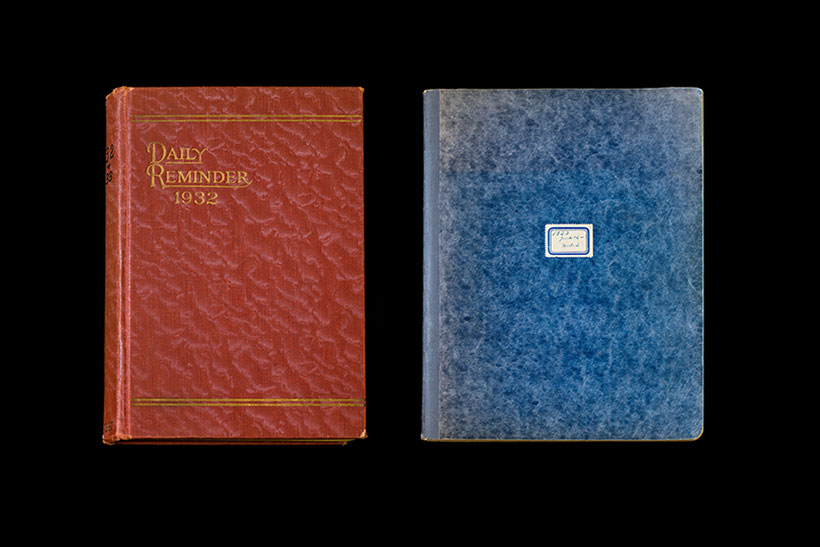

In a fitting epilogue to the career of an instructor whose personality was especially intertwined with his teaching, the College’s Archives and Special Collections has acquired 60 years of private diaries kept by Baird and his wife, Frances, known as Bertie.

Late this winter, Tom Fels ’67, one of Baird’s students during the final years of English 1-2, left Paula and Walter Auclair’s farmstead in Pittstown, N.Y., his Subaru Outback filled with old composition books and binders of pages penned by the Bairds, Amherst-bound. Paula Auclair had inherited them from her mother, Alice Machlett, Bertie Baird’s sister, who had received them after the Bairds’ deaths in February and December of 1996. She felt it was time for the diaries to return to Amherst.

Ted Baird taught at Amherst from 1927 to 1969, and Bertie was a Smith professor for several years. They lived on Shays Street, in a home they commissioned from Frank Lloyd Wright in 1940, the only Wright house in Massachusetts.

The diaries, amounting to some 21 feet of material, have tripled the amount of Baird-related material in the College’s archives, joining correspondence between Baird and his students and colleagues, some curriculum materials and manuscripts published and unpublished.

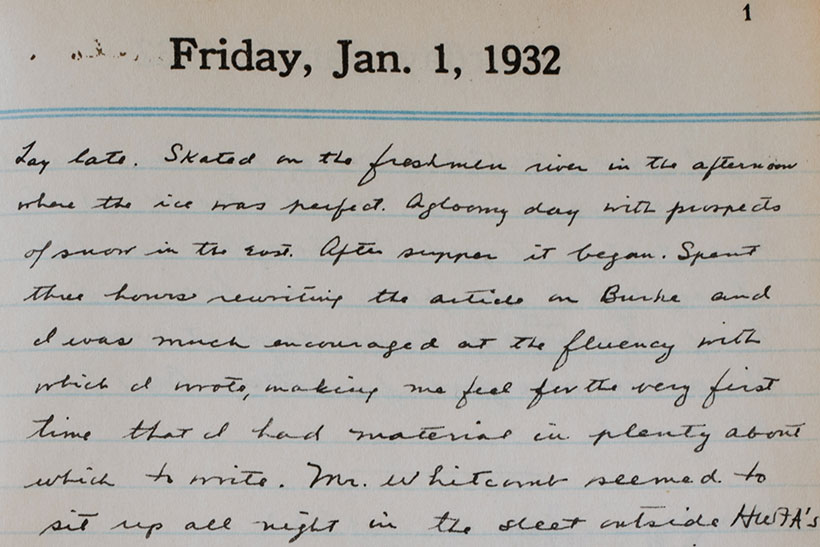

The journal’s contents are largely still an unknown to the College’s archivists.

Archives intern Elliott Hadwin ’19 has been getting to know the Bairds in recent weeks, vacuuming decades of dust from many of the volumes, and filing them in chronological order, learning little bits about the couple as he makes his way.

“They are writing every single day, together,” sometimes about the same events, Hadwin says. “You get an idea of how different their lives are. He, as an Amherst professor, gets to be a little more up in the clouds,” while his wife might be more focused on the practical side.

The diaries include accounts of Robert Frost, who taught at Amherst through much of the first half of the 20 century. Among the few news clippings in the diaries is a June 17, 1938, article from The Amherst Student about Frost’s resignation following the death of his wife Elinor.

Baird was notoriously uninterested in publishing, and instead focused on teaching, developing the English 1-2 composition course, which had a new set of assignments each year and in which a whole semester’s focus would be on a question such as, “Where are you?” “What is a game?” or “What or who is your true self?”

The course could be tough on students and instructors alike, recalls a former colleague, Kim Townsend, the Class of 1959 Professor of English, Emeritus, who taught English 1-2 in the 1960s.

“First of all,” Townsend says, “there are no books. The substance of the course is wholly the students writing, over the fall, 33 assignments. Everything depends on the dialogue between teacher and student, the comments that one would make in criticizing and redirecting.”

The course was unusual enough for its time, and with rippling impact, to warrant the National Council of Teachers to publish a 1996 book about it, Fencing With Words: A History of Writing Instruction at Amherst College During the Era of Theodore Baird, 1938-1966, by Robin Varnum. In a previous essay about the course, Varnum wrote, “It served to turn high school boys into men who questioned the authority of received wisdom.”

William H. Pritchard ’53, Henry Clay Folger Professor of English, Emeritus, edited two volumes of posthumously published Baird essays. “He was a man of very strong taste, and he really was pretty much of no two minds about anything,” Pritchard recalls: “He liked it or he didn't like it. He admired it or he didn't admire it.”

It’s a trait evident in the diaries. In one entry, for example, Baird dismisses a new author before describing a trip to the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair:

“July 13, 1933: Read Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall, a low dull book. Quite exciting however, to be going to Chi and the Fair. At the Stevens’ we cleaned off the grime from the train and made our way to the North entrance by taxi. … Strolled on, stopping for 25-cent beer at the Streets of Paris. We walked the 3 miles to the end of the Fair, buying a few souvenirs, going to see Rumba.

Remember the smell of the Fair.”

The sheer scope of the diaries, offering two lifetimes of observations painstakingly preserved, potentially offers researchers a bounty that transcends the specifics of a single course or its instructor.

“There's such a vastness of time,” Hadwin notes, “everything from the Great Depression, World War II, the civil rights movement, the college going coed, the end of fraternities—huge college events will be covered in this.”