Colonne (1932)

This bronze polychrome sculpture is the work of Anton Prinner. Its vibrant, irregular and angular sides play with the concept of dimensional expansion.

The early 20th century was a sensational time for being able to see and name, finally, much that had been hidden before.

The x-ray machine was invented in 1895, for instance, making the body dramatically more visible. Freud was kicking down the door to our subconscious. After 1915, Einstein’s theory of relativity blew up old concepts of space and time.

This chain of scientific breakthroughs inspired the day’s artists too. Cubists such as Picasso, thrilled by the new math of the fourth dimension, distilled art to geometric schemes. Surrealism gave us Dalí’s melting clock. There was Dadaism, Futurism.

Another art movement burst on the scene then, too—though this “ism” never quite made the cut.

It was called Dimensionism, and it was also eclectic and fresh. Yet adverse circumstances—especially World War II—conspired to push it into obscurity.

Which is why Dimensionism: Modern Art in the Age of Einstein, a spring and summer exhibition at the Mead Art Museum, is an act of unveiling, homage and rescue.

It has also elevated the national profile of the museum, because Dimensionism is the Mead’s first-ever traveling show. It debuted at UC Berkeley, and will later head to Rutgers. The middle run, at the Mead, goes until July 28. A book on the exhibit, written by its Mead-based curator, is now out from MIT Press.

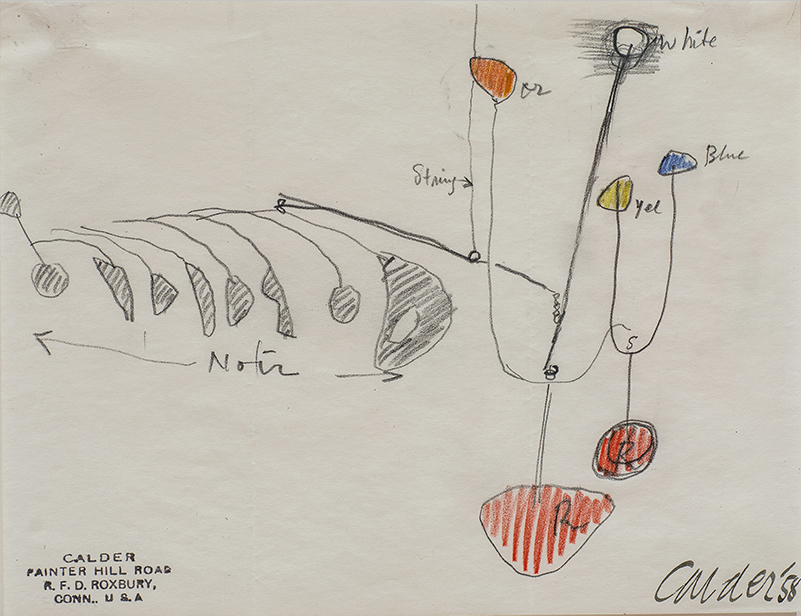

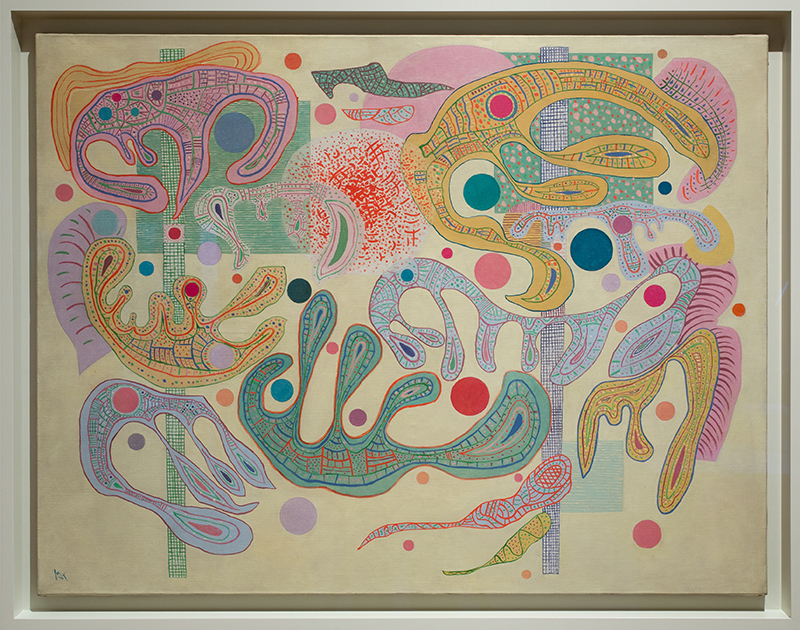

The exhibition—supported by the Henry Luce Foundation and the Terra Foundation for American Art—features 70 works, mostly from the 1930s and 1940s, that explore this historic, explosive nexus of art and science.