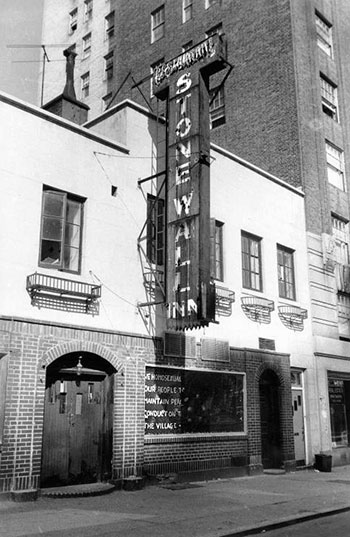

A few years ago, when the National Park Service resolved to create a national monument site at Stonewall, the Manhattan gay bar where the famous gay rights riots broke out in 1969, it turned to LGBTQ+ scholars across the country. One of them was Jen Manion. She’s an associate professor of history and the author of the forthcoming Female Husbands: A Trans History, 1740–1910 (Cambridge University Press, 2020). At her office in Chapin Hall, Manion sat down to discuss not just Stonewall but other, lesser-known protests in LGBTQ+ history.

News & Events Stonewall, 50 Years Later? It’s Complicated.

KW: How did you first learn about Stonewall?

JM: I took a college class on the history of the 1960s. And that’s where I first learned about everything: the anti-war movement, the civil rights movement, the women’s movement and finally the LGBT rights movement—near the end of the course, of course! It was not long after Martin Duberman’s book on Stonewall had come out, which became the definitive and popular history of that event.

KW: What college was this?

JM: I was at the University of Pennsylvania. And why that’s interesting is that Stonewall is actually a very New York story. Because it’s a New York story, it’s an American story, it’s a national story. It gets the attention. But Philadelphia has a very rich and older history of LGBTQ activism. And there were protests elsewhere outside New York too, like the Compton’s Cafeteria Riot in San Francisco in 1966.

KW: Tell me about Philadelphia’s Annual Reminders protests—held to remind the public that gay people did not yet have the same rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

KW: Tell me about Philadelphia’s Annual Reminders protests—held to remind the public that gay people did not yet have the same rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

JM: A Penn graduate student at that time was finishing up his thesis on the lesbian and gay movement in Philadelphia from the 1940s through the 1970s. His work was cutting-edge, re-periodizing what we thought we knew about the movement. And that’s where I learned about the Annual Reminders. It’s one of the earliest organized protests for LGBT rights, organized by the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis. So it was lesbians and gay men collaborating.

At that time, it was just so unusual to make a sign that said, “I am homosexual,” and walk around in the street when being gay was criminalized. People had been very visibly purged from government jobs in the McCarthy era. There were no legal or employment protections, and the social stigma alone was tremendous. They held protests from 1965 to 1969 on the Fourth of July—in front of Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell.

KW: Perfect symbolic location, right? Can you tell us a bit about being one of the scholars recruited by the National Park Service to help commemorate the Stonewall site?

The National Park Service does thorough, phenomenal work here. They brought together groups of scholars with different perspectives and strengths. The roundtable that I was invited to was specifically about Stonewall, because I’ve been doing lots of work on transgender history. One of the issues they want to make sure they get right is the role of transgender people in the Stonewall riots and after.

KW: Your being invited makes sense, since your own scholarship focuses on the carceral state and its response to gay and trans subcultures. And Stonewall, of course, began with a police raid.

JM: Homosexuality was criminalized from colonial America very early on, and it was punishable by death. Cross-dressing was also criminalized, but informally under vagrancy laws, and then later, after the Civil War, very formally and explicitly. And the rise in these explicit anti-cross-dressing laws, of course, emerged at the same time as the emergence of gay subcultures and communities. So, the carceral state has always had a tremendous role in regulating what was possible and not possible.

And that’s one reason why throughout history we do have many anecdotal examples of wealthy people, men and women, having same-sex lovers and living happy, relatively peaceful lives—because their class privilege buys them a certain amount of protection.

KW: Like the “Boston marriage,” for instance.

JM: Yeah. But when it comes to poor people, working people, the police would intensely monitor and regulate their behavior, like gender-nonconforming, trans and gay people. And people in those groups are disproportionally from racial minorities, so they end up bearing the brunt of police force and detention. That has not changed, actually.

KW: I know, also, that the trans community for a long time felt overlooked in the telling of the history of Stonewall.

JM: The trans movement has been so articulate and vocal and clear on the erasure and racism that was a part of that erasure. Trans women of color, who were more often poor, sometimes sex workers, didn’t fit neatly or respectably into the narrative that some gay organizations wanted Stonewall to capture. What is so remarkable right now is that so much of the publicity around Stonewall highlights the really important leadership of trans women who were there, and who also carried on the work far beyond this one moment and this one night.

KW: Like you said, just like other rights movements, the LGBTQ+ community has been subject to class and gender divisions too.

JM: Yes, so there are a couple very mainstream takes on Stonewall in the past decade that center gay men and marginalize trans people and people of color. And lesbians are another thing that people debate about, because Stonewall wasn’t a women’s bar. But this Stonewall critique speaks to the whole movement itself: that the experiences of gay people of color or trans people of color are not getting fully centered and addressed in the movement’s priorities and funding.

JM: From reading about Stonewall and talking to people who were there or who lived at that time, they describe it as a real turning point from shame to rage, and from paralysis to action. They say you cannot underestimate the power of that moment and the visibility and then the phone call chains and the storytelling and the newspapers. To support that claim, people point to the dramatic increase in gay and lesbian organizations that proliferate all over the country in the next five years. That mobilization is real.

KW: Still, you didn’t hear about Stonewall until you were in college.

JM: No one in my life or my community or my activism ever talked about Stonewall. And partly it’s because I was in Philadelphia, which had this robust LGBTQ community of its own. Also, even in the early ’90s, it still felt pretty early in the struggle. There were still so many things that people were fighting for. It wasn’t like we were looking back fondly and reminiscing about moments like Stonewall.

KW: So then how does Stonewall become such a huge symbol?

JM: One of the ways this happened is because people organized parades to commemorate Stonewall the following year. And that became Pride. It wasn’t just that Stonewall happened in June. It was that a group of people consciously said, “We have to commemorate this. We have to get people in other cities to commemorate it with a parade or a protest or something.” We have Pride parades in June, and it’s all referencing back to Stonewall.

And some of it was because of the times. By 1969, it was a time of social protests and movements. But the Annual Reminders, in 1965, had been very disciplined and orderly. People dressed very formally, in gender-conforming clothes, under very strict orders not to interact, not to intentionally incite conflict or controversy. And after Stonewall happens, and in the context of the anti-war and civil rights movements, people just felt like they were ready for more. To take to the streets, to be more combative, more expressive, more everything.

KW: Did it help that Stonewall, the actual gay bar, the actual building, was open on and off for years after the riots?

JM: Yes, it was available as a destination when so many other gay bars had short life spans. Then so many organizations named themselves after Stonewall: Stonewall Democrats, Stonewall Running Club, Stonewall Reading Club, Stonewall Bookstore, The Stonewall Literary Prize.

KW: Yes, and we have a Stonewall Prize here at Amherst too, given to students who produce exceptional work about the LGBTQ+ experience. And at Moore Hall, there is now the Sylvia Rivera Community for LGBTQ+ folks, named for the Latinx trans activist who founded STAR House, the first homeless shelter for queer and trans youth. Rivera also is renowned for her activism in the Stonewall riots.

So, in the end, how would you characterize the legacy of Stonewall?

JM: There are many throughlines. If you look at the most privileged among us, some of us are doing pretty well. The hardship and stigma of being gay or lesbian is much less than it was a generation or two ago. The legalization of gay marriage was a tremendous milestone. But when you look at the most vulnerable among us, in many ways, we’re not doing well.

KW: To your point, I’ll just quote you back the statistics from your article on the significance of Stonewall: “Over 40% of incarcerated women in the U.S. are sexual minorities. A whopping 16% of transgender adults have been in prison or jail, over five times the rate for all adults. A devastating 44% of LGBT youth report being threatened, injured, or bullied at school, and nearly one-third have attempted suicide.” I mean, those are crushing statistics.

JM: Devastating. So how do we celebrate the victories that were hard-won since Stonewall—and that, a generation or two ago, people couldn’t even dream of—and not lose sight of all of this ongoing bias? This suffering that’s so real? Recently, the NYPD apologized for Stonewall. And that’s great. And if they actually want to put that apology into action, they would look at their policies and practices of harassing street youth and gender nonconformity, and the criminalization of sex work, quite frankly.

KW: I know this 50th anniversary of Stonewall matters greatly, but I also know there are ambivalences.

JM: It’s true that some of us have expressed a kind of “Stonewall fatigue.” But it’s not because we don’t think that history matters, right? In some respect, we’ve arrived, so the gay movement has its moment, and this one event that is filling up the room and taking up all the air. There are more stories than Stonewall.