By Way of Biophysics

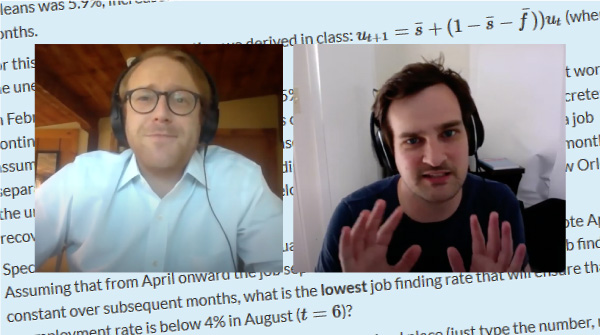

“The literature was just pouring out, and it was all fresh,” says Professor of Physics William Loinaz of the rush of new studies of COVID-19 this spring. “Here we had a new subject where we didn’t know anything about it, but it did fall in our domain of biochemistry and biophysics.”

William Loinaz and Sheila Jaswal. Photos by Ben Barnhart.

And so Loinaz and Sheila Jaswal, associate professor of chemistry, decided to channel that fresh literature toward the final unit of their 19-student capstone course “Molecular and Cellular Biophysics.”

In one class meeting, for instance, they focused on a recent paper breaking down the mechanics of the virus, and invited its co-author Rob Phillips, professor in bioengineering at the California Institute of Technology, in for a Zoom talk. He was joined by Amy Kistler and Josh Batson, members of the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub COVID-19 research team.

“It felt like it mattered,” says Donna Roscoe ’21, of parsing COVID-19 studies and hearing these expert voices. “Once your whole world is uprooted, it’s kind of nice to at least have an excuse to focus on it.”

Early on in the unit, students broke up into groups and, via teleconferencing, discussed how a viral infection works and the psychology of living through a pandemic.

For their final projects, students worked on ways to teach others about COVID-19—including future students in the course. Some wrote letters to their families and others they felt might need to hear the hard science.

Class member Amila Semic ’20 illustrated aspects of the COVID-19 virus and the main protease. See larger image.

“Through conversations with scientists on the front lines, immersion through primary literature, and the solitude of quarantine, I have begun to realize that the best knowledge to arm ourselves is an intimate understanding of the numbers that are driving this virus,” Chris Daveiga ’20 says in his letter.

Other students described the virus and its impact through poetry and art. Amanda Lopez ’20 hosted a Zoom meeting for friends, outlining what scientists currently know about the virus. Ava Simoncelli ’20 shot a video (below) of her family and friends in masks, superimposed with facts about the virus, such as this: COVID-19 has a lower mutation rate than the common flu, “which means a possible longer period of effectiveness for vaccines/treatments.”

Roscoe, in addition to her final project, prepared a Google Doc of helpful links, dubbed the “Amherst College Biophysicist-Approved Collection of Coronavirus Information,” or ACBACCI—pronounced “Ack-Back-Eee,” an appropriate verbal response to the virus, she says.

“One of the worst parts of this pandemic is the lack of concrete knowledge regarding the virus,” Roscoe says. “It’s best to learn things straight from the scientists and scientific articles themselves.”

Aditi Nayak ’23, not a student in the class, says she is publishing some of the students projects in the Amherst STEM Network, a student-run online magazine that highlights Amherst achievements in science.

Each project plays off the goal of the course itself. Its “core function is about evaluating the scientific literature: reading it, dissecting it, putting it together in different ways,” says Loinaz.

And though it’s a situation that no one asked for or wants, coming to terms with COVID-19 has put the class to good use, Jaswal says: “We’re not giving you answers. It’s no longer a pre-digested textbook for you. If some questions are kind of confusing? That’s real life.”

—Bill Sweet