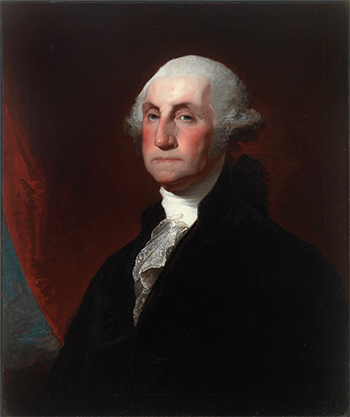

George Washington (1732–1799),

ca. 1800, Gilbert Stuart

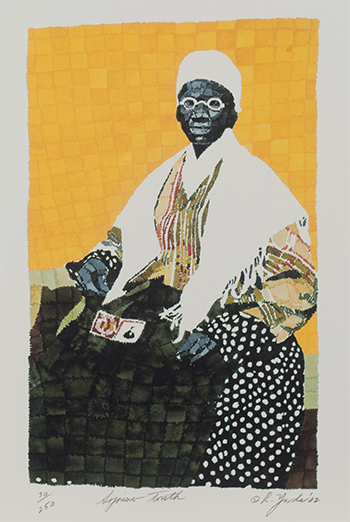

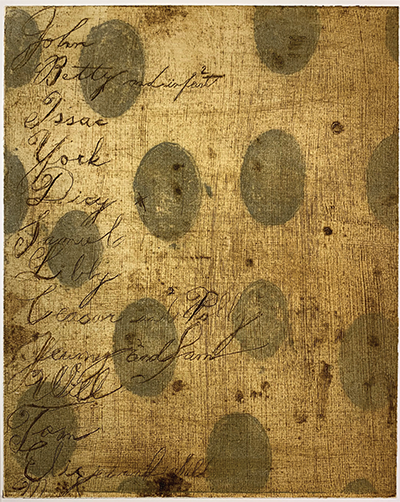

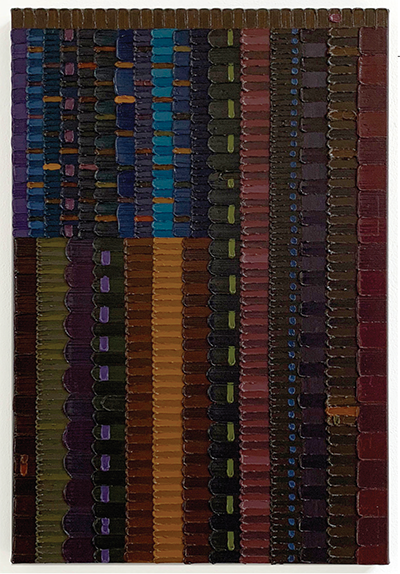

“I see it as the start of a conversation,” says Lisa Crossman, curator of American art and arts of the Americas at Amherst’s Mead Art Museum. She’s talking about her first Mead exhibition, Founding Narratives. It displays art from the Mead collection made in the United States between 1800 and today: an iconic presidential portrait, arresting landscapes, a representation of the U.S. flag based on brown skin tones. Crossman hopes viewers will consider each work for the stories the artist may have intended to tell and for those told by others over time. Founding Narratives critically considers the boundaries that have defined “American” art, both in general and at the Mead, and Crossman intends it to be the first of many Mead shows to present “more diverse and inclusive stories about art produced in the United States.” She says: “I look forward to continuing the dialogue.” Created with intern Maya Foster ’23, the exhibition will be on view spring semester for those on campus and is available virtually to all.