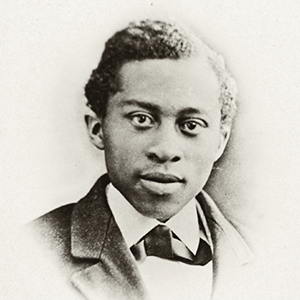

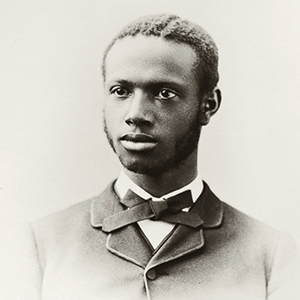

Charles Henry Moore Class of 1878

The Black residents of Tarboro, N.C., crowded into a tobacco warehouse to hear Moore speak. He talked for an hour. He had done many such talks, traveling 12,000 miles from town to town in his home state. On this day in 1917, he again made his case: State appropriations for Black schools are “pitifully small,” and so we must build new schools ourselves.

An elderly man offered $23.45, the bills and coins tucked in a soiled rag. Soon, the others pitched in too, raising a total of $600.

Moore described this scene in the article “Rosenwald Schools in North Carolina.” These schools were an effort thought up by Booker T. Washington, leader of the Tuskegee Institute, and funded by Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears Roebuck. Some 5,000 Rosenwald Schools were built between 1915 and 1932, a third of the total of Black schools in the South. Moore was the Rosenwald agent for North Carolina.

Earlier, Moore was North Carolina’s first state schools inspector. He turned up extensive evidence of inequity, as white schools siphoned off funding meant to be split with Black schools. At times, Moore faced hostility on his visits and had to escape at night for his safety.

His efforts spanned wide: Moore was a founder of the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University. Today, the university has a research lab named in his honor. He became a teacher and principal in Greensboro, N.C., and helped to organize the North Carolina Teachers’ Association. A local grade school was named for him.

Born into slavery, he died in 1952, at age 97, two years before Brown v. Board of Education.

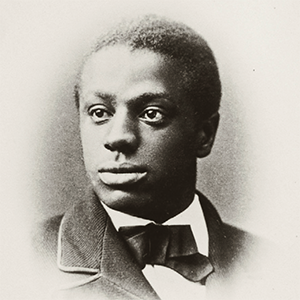

Wiley Lane Class of 1879

Frederick Douglass spoke at his funeral.

Douglass had found “surprise and delight” hearing a lecture from Lane, the first African American professor of Greek at Howard University. Said Douglass: “He was a rising young man and an honor to humanity.”

Lane died at age 32, of pneumonia, in 1885. As Howard professor Francis L. Cardozo eulogized: Lane wanted to occupy the position of Greek professor “so that he might aid in removing the stigma on his race of their inability to fill such positions.”

Lane was born in Elizabeth City, N.C., in 1852, the child of two free parents, and was drawn to Amherst by its illustrious classics department. He was Phi Beta Kappa at Amherst.

Lane took a robust role in Black intellectual circles of Washington, D.C., and is now part of the traveling exhibit 15 Black Classicists, created by Wayne State University Professor Michele Ronnick. As she told The Guardian: these historical figures are “waiting patiently for us to find them. It is an intellectual heritage in which all Americans can take pride.”

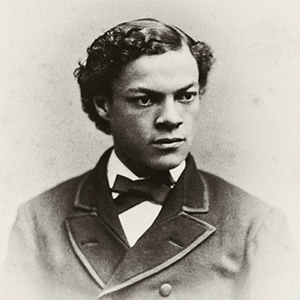

Wilbert Lew Class of 1883

Wilbert Lew did not educate people—but he likely educated horses. That was a phrase in fashion: to “educate” a horse meant to break him of bad behavior.

Lew learned his craft from a top horse whisperer. There were almost no official veterinary schools at the time. It wasn’t until 1945 that Tuskegee started the first program for Black veterinarians.

In census and directory records, Lew is listed as a veterinary surgeon and dentist in Florence, Mass. He was born in Gardner, Mass., in 1861. His father’s occupation is listed as “hair dresser,” his mother’s as “keeping house.”

There was an ad for his services in 1891: “Dr. Wilbert B. Lew, Veterinary Specialist and Dentist.”

In 1920 he was named “inspector of animals” for the Town of Amherst. He died in 1923, after four decades of treating and educating horses and other animals, and riding into the dawn of a new profession.

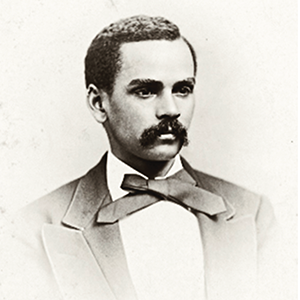

Photos from Amherst College Archives