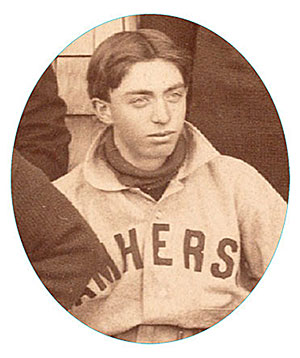

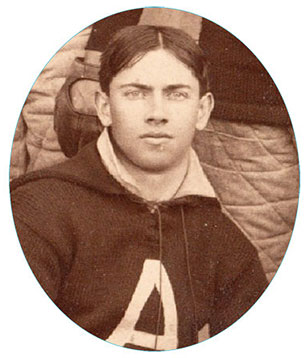

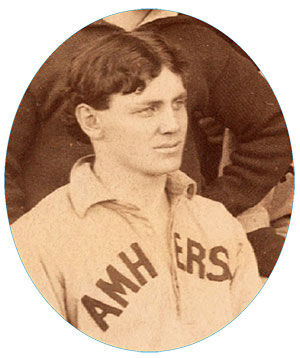

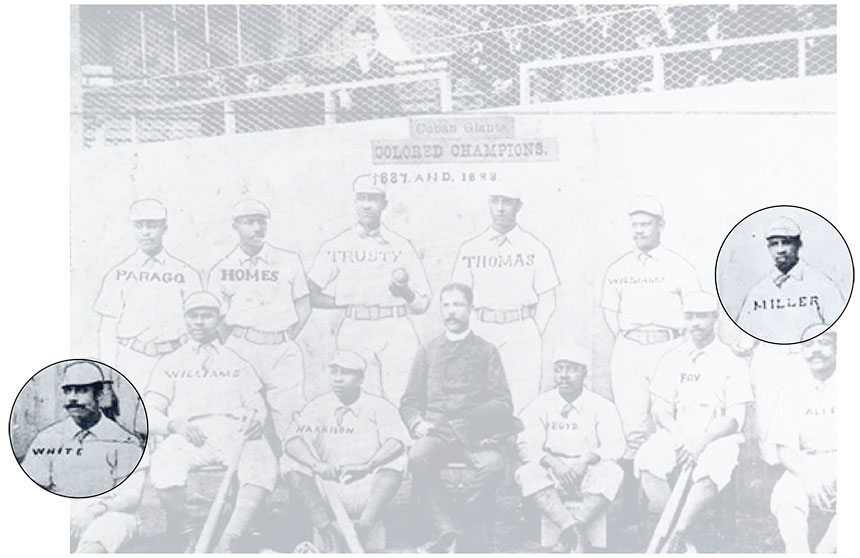

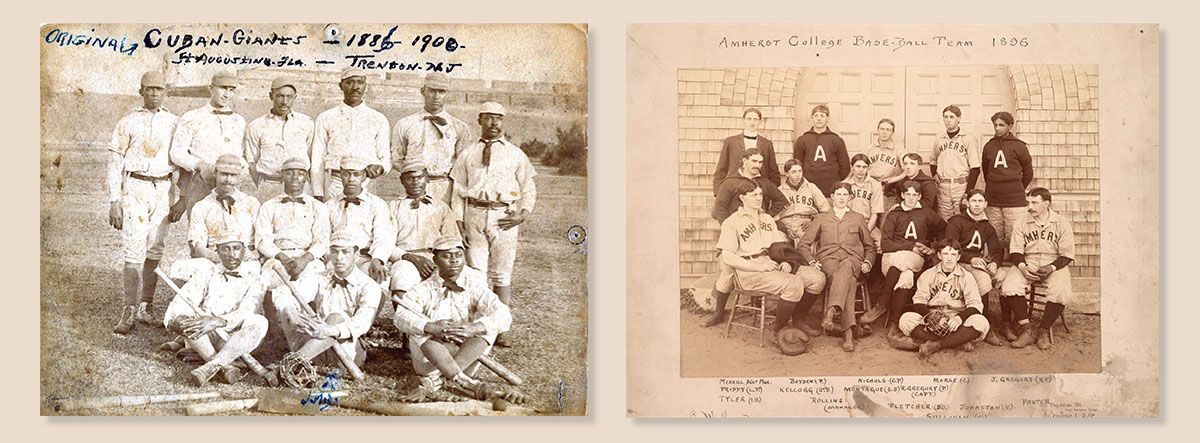

(left) The Cuban Giants, 1886-1900; (right) The Amherst College baseball team 1896. (Click on image to enlarge.)

In March, I was flipping through The New York Times Magazine and was struck by a piece with this provocative title: “Justice for the Negro Leagues Will Mean More Than Just Stats.”

I read that, since Major League Baseball announced, at the end of 2020, that it would start incorporating Negro-league player stats, a deep discussion has been happening around issues of acknowledgment and atonement for decades of baseball segregation. The MLB didn’t integrate until 1947, when Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers.

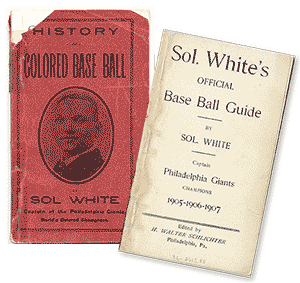

The Negro Leagues technically launched in 1920. Earlier, Black athletes played on integrated teams (until around 1887) and on all-Black teams that presaged the Negro leagues. The MLB must now assess decades of statistics. If you are a baseball fan like me, your sports trivia knowledge will be radically refreshed once these stats become official. Which pitcher, for instance, threw a no-hitter on opening day? The MLB answer won’t just be Bob Feller, but now also Leon Day. Who hit over .400 for the season? Not just Ted Williams, but Josh Gibson.

This is all remarkable. But what does it have to do with Amherst?

You’d guess nothing, but then I spied this tantalizing clue in the Times: Author Rowan Ricardo Phillips mentioned seeing memorabilia from games between the Cuban Giants, the first Black professional baseball club, and Wesleyan’s varsity baseball team in the 1890s.

It hit me: Did the Cuban Giants challenge the other two of the Little Three?

Spoiler alert: The College lost—but just barely, 7-6, in a 10-inning game. You can gloat at Amherst’s respectable showing: the next day, the Cuban Giants trounced Williams 16-8. The Boston Globe called the Ephs’ fielding “wretched.”

Yet the stats from these games won’t funnel into MLB standings: only play from 1920 to 1948 is being considered. The MLB holds that the games before 1920 don’t count, labeling them as lower-quality, a run of loosely recorded exhibition games and barnstorming tours.

Negro-league players and achievements matter on their own, not just because the MLB recognizes them, of course. And deciding what constitutes “low-quality” play is a debatable, even troubling, pretext for excluding the early days of Negro-league ball. (Note: The MLB started long before 1920, the National League in 1876, the American League in 1901.)

As Phillips wrote: “Are we separating 29 years of Black baseball from its 100 years of history just because some box scores are available?”

While the MLB is dismissing stats before 1920, the National Baseball Hall of Fame has inducted several Negro-leaguers from the earlier era.

A word about the Cuban Giants. No player was Cuban: the moniker is part of a pattern of concealing African American origins from white spectators. The team was founded in 1885 to entertain guests at a beach resort hotel in Babylon, Long Island, had a home base in Trenton, N.J., toured the northeast, and spent some winters in Florida and, yes, Cuba. The key to making baseball financially viable was to play year-round.

The Amherst game is part of the history of segregation, but also of integration. The College’s one Black player, James Francis Gregory ’98, was the first Black student to be named captain of an eastern college baseball team. He was the son of a Howard University professor, and his family tree includes both Charles Drew, class of 1926, who pioneered methods for storing blood plasma, and Supreme Court Justice Roger Taney, who delivered the majority opinion in the Dred Scott decision.

Below, you can dive into the story of this game and these players. Such recollection is just one small step toward elevating the history of the Negro Leagues.

Further Bicentennial Reading

Amherst College Bicentennial Website