In August 2019 I took a train across the country to Los Angeles. I had never been there; to prepare, in the middle of the night when I couldn’t sleep, I read Mike Davis’ book City of Quartz. It begins with a quotation:

“Los Angeles, it should be understood, is not a mere city. On the contrary, it is, and has been since 1988, a commodity: something to be advertised and sold to the people of the United States like automobiles, cigarettes, and mouth wash.”

I was moving there to do paid work for UCLA and unpaid work for the Los Angeles Tenants Union. No one in the tenants’ union knew I existed, but I had read enough about them to have made a private, mental commitment.

I had begun learning how to organize tenants a few years earlier, as a graduate student in Boston. It was initially an anger-management technique: I was full of despair and rage about the state of the world, and the only people I knew who had as much rage as I did and were doing something about it were trying to start a tenants’ union in Philadelphia.

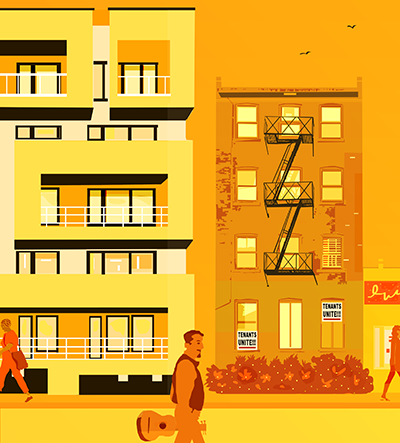

Most people have never heard of a union for tenants. When poor and working-class tenants face rent increases, slum conditions and mass evictions, what’s happening to them is generally not framed politically, as a matter of class power. Instead, those who are lucky are directed to lawyers or to housing nonprofits, where they might get help with their individual crises. What tenants need, however, is a way to make these individual battles collective, and that’s what I wanted to help build: an organized force that could change the political terrain of a city.

As I tried to learn how to organize in Boston, I read about a similar effort underway in Los Angeles. “Gentrification,” members of the L.A. Tenants Union wrote, “is the displacement and replacement of the poor for profit.” In 2017, when a group of mariachi musicians in the Boyle Heights neighborhood learned their rent would increase by $800 a month, this union had organized a rent strike and forced the landlord to negotiate. Struggling to organize a complex in Mattapan, a working-class neighborhood of Boston, where tenants were also facing impossible rent increases, I appreciated how much skill and dedication it must have taken to organize a successful rent strike.

Two weeks after I moved to L.A., I found my way to an office building in Koreatown for a meeting of my local chapter. Luxury hotels and apartment buildings had started to go up a few years earlier, and the room was full of tenants who were in drawn-out battles with their landlords. A few were fighting evictions enabled by the Ellis Act, a loophole that allows landlords to remove tenants from rent-stabilized housing; some were dealing with illegal construction, intended to make their lives so miserable that they would move out; others were facing cash-for-keys harassment, carried out by professional “relocation specialists” who threaten and lie until tenants agree to leave rent-stabilized apartments in exchange for money that will be gone in a year.

This meeting, between the kind of tenants who were being cleared out and the kind of tenants—like me—who developers were hoping would replace them, was possible because everyone wore an earpiece, and two interpreters switched off throughout the meeting, providing simultaneous interpretation so that English and Spanish speakers could understand one another. That kind of communication, across deep social divides, did what nothing else can: it allowed us to see more clearly our places in the social order, and what kind of solidarity we would have to build to overturn it.

The churn of the academic job market has deposited me back in Massachusetts, heartsick for the union. What Los Angeles ended up being to me, over two transformative years of profound social crisis, was a map marked by sites of collective struggle: Seoul Park, where we brought tenants facing harassment to meet with tenants who’d fought the same landlord and stayed; 6th and Alvarado, where we marched together during the George Floyd protests; Echo Park Lake, where 400 police officers in riot gear came to remove people living in tents; and countless buildings where we fought illegal evictions and held tenants’ rights workshops.

The word for what we in the union are to each other is comrades. I used to cringe when I heard that term used seriously. But I’ve learned that its value is in naming a distinctive social relation. I know elaborate details about the lives of many people in the union; about many others, all I know is that we share an understanding of how this cruel world works, and the will to fight for a different one.

Lenehan is a fellow in Amherst’s Center for Humanistic Inquiry and a visiting lecturer in the philosophy department for 2021–23.

Illustration by Kim Demarco