Annie was the first woman to journey around the world on a bicycle; Zheutlin, her distant cousin, first revived her forgotten legacy in his 2007 nonfiction book, Around the World on Two Wheels. In Spin, he goes further, humanizing Annie by imagining her inner life against the backdrop of world events. This is the height of the women’s suffrage movement. It is a time when many women tied to passionless, loveless marriages were secretly involved in romantic affairs with other women. Barely out of her teenage years, Annie begins an arranged marriage to an older man and bears three children in quick succession. Worse, not only is she the chief homemaker, but her husband has dedicated himself to the faith and forced her to earn most of the family’s income. She is a woman who feels no maternal instinct and has never wanted children. I empathize with her. I can perhaps even get over my disappointment at her refusal to be the heroic protagonist I want her to be. At the start of the novel, I was hoping for some Phileas Fogg-like adventures in Arabia and India; what I got was the reality of just how hard women have worked over the centuries to ensure the freedoms I enjoy today.

Annie understands that story-making is far more important than actual deeds in altering people’s perceptions. In agreeing to bike around the world, she is tasked with proving that a woman can do whatever a man can do. However, the man who sends her on this mission does not, not even for a moment, consider that his world is built precisely so that women fail outside the home. Annie, well aware of this reality, plays her best cards. She is coy when she needs to be, commanding if necessary, cheery even when she does not feel it, somber and proper among those (men) she needs to make feel less threatened. She manipulates anyone who can be manipulated. She lies to win the wager that has sent her on her quest because this is the only way she can justify to herself and her family a decision that fills her with such guilt.

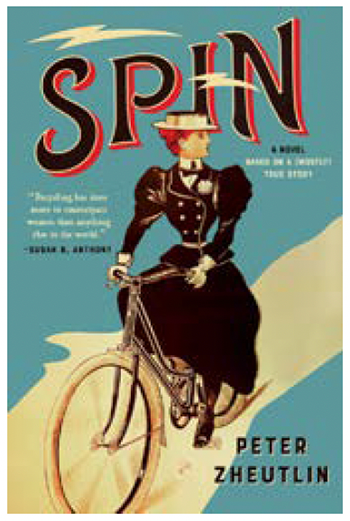

Spin

By Peter Zheutlin ’75

Pegasus

Annie makes me feel deeply uncomfortable. This is because I like her and wish she were a better person. At times, I wanted to pinch her: Annie, we need to talk. Other times, I wanted to embrace her and keep her safe. The consequences of her decisions on others are difficult to look upon, and also difficult to ignore. I am torn, and I am certain that you will hate Annie as much as you come to love her. She says of her decisions, “They were selfish, to be sure, but I doubt my life would have been better had I not made them.”

Therefore, dear reader, jump in! For a few hours, escape whichever hole this pandemic has forced you into. Pedal through the mud with Annie; sleep under the stars; pant your way up horrid hills and hurtle down dangerously on a brakeless, 19th-century bicycle; endure deluges and cold and a bout of pneumonia; venture into the desert’s scorching heat (beware of scorpions); stop by the Moulin Rouge; skip around the British colonies; put up with arrogant, self-absorbed fools; dodge the starstruck; have an affair or two; turn down lots of marriage proposals; get shot at for a good sum of money; lose a bicycle or two; confuse and offend the proper and prim; cross paths with murderers (real and imagined); inspire millions of men and women; do something that no one in your station would ever imagine doing. Then come home, and perhaps you will be as full of grief as Annie is until the end. Perhaps you too will feel that there is no right way to live.

Onjerika won the 2018 Caine Prize for African Writing, was shortlisted for the 2020 Bristol Prize and was a 2020 Best of the Net nominee. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Black Warrior Review, The Adroit Journal, Granta, The Johannesburg Review of Books, Fireside Quarterly, Wasafiri, New Daughters of Africa and elsewhere. She founded and teaches at the Nairobi Writing Academy.

Illustration by Isip Xin