Tamara Johnson ’73 had a great ear. Her Amherst friends all remember how they’d sit in her dorm room while she spun classical records for them, talking about the music’s intent, its power, especially the arias of the sublime Black divas of the day: Betty Allen, Grace Bumbry, Leontyne Price. “She was totally in heaven when she was listening to Leontyne Price singing Aida,” says Ted Lenox ’73. “You could see her just going off into a trance, elevated to another world.”

Johnson didn’t just absorb or analyze music; she played it. Growing up, that meant the organ at her family church in the St. Albans neighborhood of Queens, N.Y., and the piano for local fashion and variety shows. She was the accompanist to her high school choir, and on her early decision application to Amherst, Johnson wrote that her musical gifts gave “the satisfaction of serving my friends, home, community, and most important my God.”

She had a fine voice, also, singing first tenor at Amherst and in Queens. She even did a short European summer tour with her high school chorus, and that plausibly changed her life. I say “plausibly” because plausibility is all I’ve got for much of this story. I never spoke to her; Tamara Johnson had a chronic illness and died in 1994, at age 43, in Munich, Germany. The grief still wounds those who loved her, or at least those whom I could find or who would speak to me for a reporting experience as full of roadblocks as epiphanies. That’s how it often goes when you cover someone who was part of a marginalized community or, in her case, several marginalized communities.

Tamara Johnson was a woman ahead of her time, and, to our current knowledge, Amherst’s first transgender graduate.

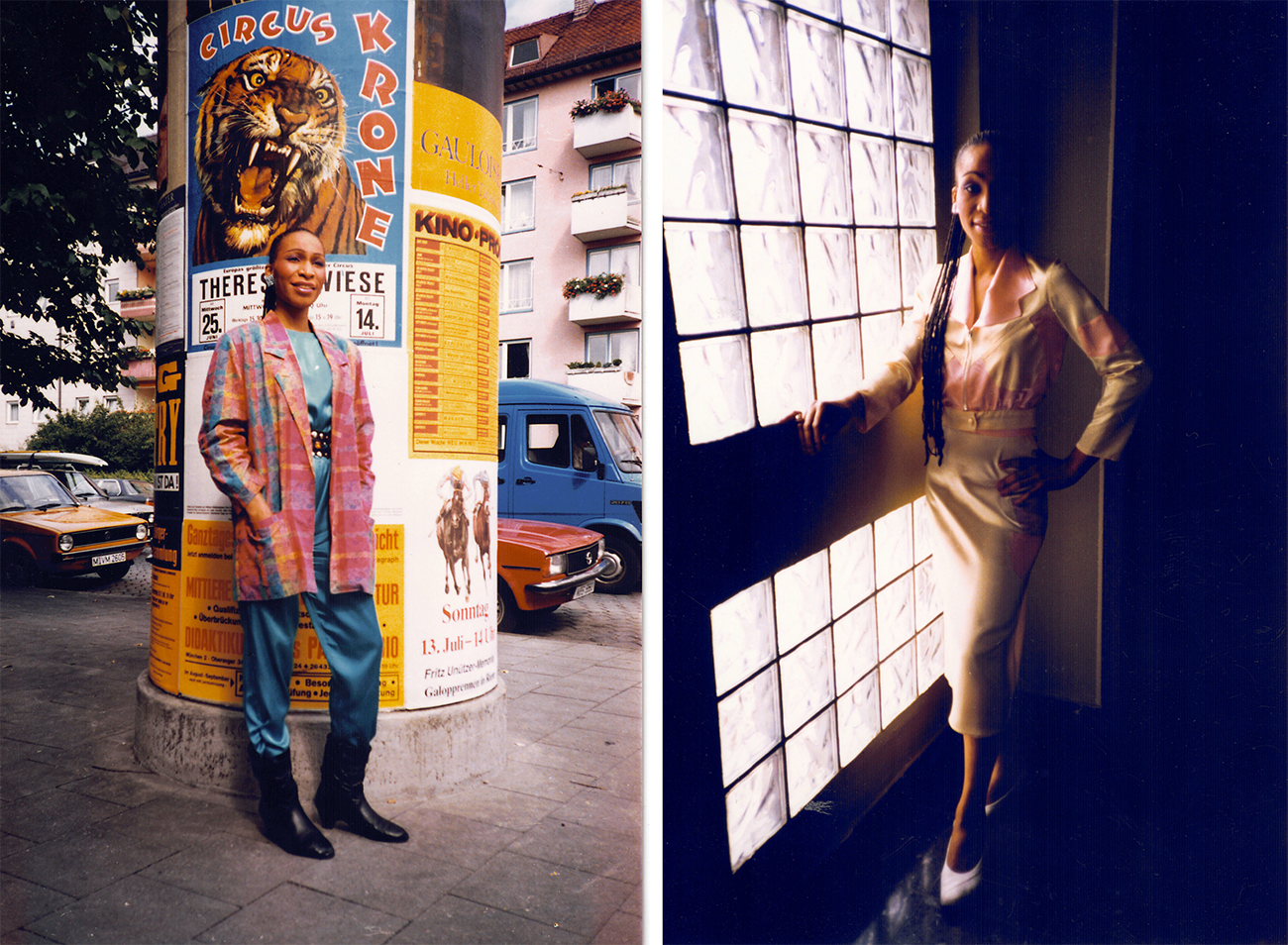

“Tamara wouldn’t allow people to tease her or insult her. She was optimistic, charming, charismatic. She was both a very interesting person and a very interested person.” Photos courtesy Annemarie Wimmer

I, Raffaela Tamara Johnson … have undergone a change of sex operation from male to female since my graduation at Amherst and need to have my transcript and bachelor of arts degree changed over to the new name... .” So went the matter-of-fact and, at that time, unprecedented note she wrote to the College in 1982. She required the documents to attend school in Munich. (Throughout this article, I will avoid using her so-called “deadname”—the name assigned to a trans person at birth but no longer embraced—as Johnson is not here to give consent to include it.)

We don’t know exactly when Johnson began to actualize her trans identity to the world, but the process had some antecedents at Amherst, where she wore a dress to at least one party, and then after graduation, when she settled in Europe. Johnson sent pictures of herself to her Amherst friends throughout the 1970s in which she is wearing makeup, dresses and heels. She often included some cash in the envelope for her friend Leroy Culton ’76 so his sister could buy and send her some Fashion Fair cosmetics, a brand for Black women then unavailable on the continent.

Whatever the trajectory of her inner journey, we can make the case that Johnson realized early on that Europe equaled possibility. She took all kinds of courses at Amherst, from music to philosophy to literature, but made sure to major in European studies—and set her sights on Paris. She enrolled in the Sweet Briar College Junior Year in France program and, instead of flying over, chose to sail in on the Queen Elizabeth 2. “She wanted that transatlantic experience so she could begin to weave her life in a different perspective,” says her friend Harold McCray ’73. “She met a lot of people on the boat, and when she got to Paris, she felt changed. She felt liberated. She felt as if this was her opportunity to live her life as she did.”

In France, Johnson seems to have experimented with her gender expression: she stood on towering platform shoes and sported “a big Angela Davis-like Afro wig,” recalls McCray*, who also studied in France that year. She was attracted to men and had been unapologetically out as gay at Amherst—one of very few in a deeply closeted time and place. In Paris, she started visiting gay bars, and acquired an affectionate (or perhaps othering) nickname: “the exotic bird of the West.” When people stared at her on the street, she stared right back. She used humor as a form of disarmament, too, a habit reinforced from Amherst. “She did receive a lot of pushback on campus, but people also respected her because she was just brilliant—and witty,” says McCray. “If someone called her a queen, she’d say ‘Yes, that’s true. But are you going to curtsy or what?’”

This boldness blossomed in other parts of her life as well. In Paris, she once spied Jean-Paul Sartre at Les Deux Magots, the illustrious gathering spot for artists, and went right up to him and kicked off a conversation. She befriended an organist who played at Notre Dame, and convinced him to let her pull out the stops in the great cathedral, too. Her deepest connection, though, developed with Nadia Boulanger, the famed piano instructor who taught hundreds of Americans in Paris, including Aaron Copland, Philip Glass and Quincy Jones. Boulanger loved to invite her for tea and conversation, and eventually Johnson gave a piano recital hosted by her mentor. Her repertoire included a Bach fugue, a Chopin waltz and Debussy’s “Clair de Lune.”

Boulanger introduced Johnson to the music of French composer-mystic Olivier Messiaen, and presumably Johnson felt simpatico with Messiaen’s embrace of faith, boldness and experiment. Messiaen is best known for his “Quartet for the End of Time,” first performed in a prisoner-of-war camp in German-occupied territory in 1941, where he and other inmates played on scrounged instruments. At Amherst, Johnson did an independent study on how Messiaen tried to infuse Christian mysticism into musical expression.

She even sent the finished work to the composer himself. He wrote her back in admiration: “C’est un travail absolument remarquable, d’une grand intuition, et d’une grande poésie.” “It is absolutely remarkable work, of great intuition, and great poetry.”

Her excellent ear wasn’t only tuned for music; Johnson was talented with languages, too, and eventually spoke French and German fluently, with a decent command of Spanish and Italian. Taking language classes at Amherst seems to have been part of the strategy for plotting a life in Europe. Because there she could “do a James Baldwin,” as the Black gay writer Malek Mouzon has put it, cueing the great American writer who made his home in France and Switzerland, finding that America was too hostile to someone creative and Black and queer.

It’s not a perfect parallel, though; Baldwin spoke little French when he arrived in France in 1948, while Johnson was close to proficient in the language when she did the Sweet Briar program, practicing with her Haitian friends in Queens and winning the City French Award at her secondary school. That school, Andrew Jackson High School, no longer exists, but I was able to contact some of her classmates through an alumni Facebook group. Jackson High was once a beacon of integration. It was also a feeder school to Amherst for Black students, among them Harold Wade Jr. ’68, who wrote Black Men of Amherst.

Johnson’s family was part of the St. Albans middle-class Black community, and education was a prime value. Her parents, Herbert and Earline Johnson, attended historically Black colleges (Hampton University and Paine College, respectively). Herbert Johnson supported the family, including Tamara’s two sisters and one brother, as a public middle school teacher in Brooklyn. Johnson’s grandmother Clarice, who lived with them, was the biggest influence of her childhood. Remembers McCray: “Tamara always said her grandmother gave her unconditional love.”

I found an online copy of the 1969 Andrew Jackson yearbook—which opens with the famous Earth-from-space photo from that year’s moon landing. Johnson’s peers voted her one of two “Class Intellects,” and she was chosen to be on the school’s team for the TV high school quiz show It’s Academic. The classmates I spoke to universally cited her intelligence—Johnson would graduate from Amherst summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa—but also described her in ways I didn’t expect. “Quiet,” for instance, and a “gentle soul,” and “very much on the mild side” and “maintained a very low profile.” That didn’t sound like the person who sauntered up to Sartre. Young people can undergo a metamorphosis after leaving high school for college, of course. But you also know, scrutinizing those yearbook photos of her in slacks and turtlenecks and neckties, that she is not yet who she’s meant to me.

A few years back, Saren Deardorff ’17, a transgender man, produced a film for the College’s Queer Resource Center. Invisible No More: A Queer and Trans History at Amherst College is revealing, heartening, troubling. You learn that the playwright Clyde Fitch, class of 1886, wore skintight robin’s-egg-blue suits on campus and was rumored to have had a romantic relationship with Oscar Wilde. You find out that a homophobic Robert Frost pushed to fire Stark Young, the gay professor who helped hire Frost in the first place. You hear that the College was likely the first of its peers to add a specialist in lesbian and gay literature to its faculty (Michele Barale, now the Thalheimer Professor of Sexuality, Women’s and Gender Studies, Emerita).

About 12 minutes in, Deardorff brings up Tamara Johnson, via two articles in The Amherst Student, one written by Johnson in 1973, another a 1972 interview done with Johnson and Richard Cleaver ’74, who were trying to start a gay rights group on campus: only Amherst, of the Five Colleges, was lacking one then. Reading her words, you realize that the problem with having a great ear, of course, is that you hear the terrible things, too. Johnson had been harassed for being read as gay since she got to Amherst.

Her friend Dan Whitaker ’71 recalls how Johnson carried herself on campus. She “wore a black knee-length fur coat when most were in army surplus outfits, and walked like Salvador Dalí with a furled umbrella in front,” he says. “I was also quite flamboyant on campus, but I did it deliberately as a consciousness-raising effort.” In contrast, he says, Johnson was just being true to her essence. Whitaker told me that a straight white roommate of Johnson’s asked to be transferred to another dorm room, because any alliance with her might hurt his future career. Her friends remember that some Black classmates shunned her, too. Whitaker says notes appeared under Johnson’s door warning her to cool it, saying she was giving Amherst’s small Black community a bad reputation. She “was getting criticism,” he adds, “almost threats.”

By the time she was a senior, after having lived so much more freely her junior year in Paris, she felt compelled to speak out. Here are some excerpts from her “Reflections on Gay Life at Amherst,” published in the Student in March 1973:

For the openly gay person at Amherst, life is very closed. Each day one is expected to carry the stigma and burden for so many closet cases here in silence and submission. Each day one is expected to accept the general mockery and cries of ‘faggot.’ … Because I try to ignore your stupidity and lack of feeling, don’t interpret this as not hearing. I hear and it registers. … To my closeted gay brothers and sisters throughout the faculty and students of Amherst College (and they are many in number), I say, just remain there. Don’t bother to express your true identity and feelings. … Amherst is not the place for that. … I have served as a good example and scapegoat for all the gays here. You wouldn’t want to face it.

I won’t sidestep this distressing portrait of Amherst then: the pre-coed College mirrored the homophobia of the era. At one frat party, Lenox told me, someone threw a glass of beer at Johnson’s head. (An officer of the fraternity later apologized for the brother’s behavior.) Johnson was surely wounded by such abuse and ostracism, but she was also steeled by it. Professors admired her, such as the sociologist and socialist public intellectual Norman Birnbaum. And it helped that she had her people, a circle of solidarity and humor who regularly ate at Valentine together. Three of those friends—Culton, McCray and Lenox—talk frequently to this day. Decades later, they have deepened their perspective on what Johnson meant to them. McCray says Johnson served as a sounding board for him about the coming-out process and compassionately did the same for others on campus.

Says McCray: “If you were befriended by her, you came to admire her and actually to see her as a prototype of where to go with your identity, how to embrace who you are and live your life.”

Says Lenox: “She was one of the most courageous persons I’ve ever come across. I mean, courageous to the point that it was intimidating. But once you got to know her, she was just an amazing person. So warm, so loving and so friendly.”

When I interviewed each of these Amherst friends, I loved sharing the following reveal, because it moved them so much: Johnson’s story lives on for today’s students. Khary Polk, associate professor of Black studies and sexuality, women’s and gender studies, discusses Johnson’s Amherst Student essay in his “Queer Theory and Practice” class. He also teaches a course called “Black Europe,” and last year, he covered Johnson in a talk he gave at Boston College about Black expatriates in Germany.

I asked Polk about how he contextualizes Johnson for his class on queer theory. He said, “It was important to find tangible ways to think about queerness historically, in the contemporary moment and even toward the future—and whether or not Amherst has a history that we can work to uncover.” When he and his students did a close read of Johnson’s essay, they were struck by how other men at the time assumed that a gay man would reject the idea of coeducation. “But Johnson says she would be comfortable with women on campus,” Polk says, “and I think that foreshadows her burgeoning gender identity.”

Johnson, as a trans woman, may have been unique in her time at the College. Had she attended today, she would have found peers. Amherst does not keep official figures, but the Queer Resource Center has had dozens of Amherst trans and nonbinary students take part recently in a lively group text chat. Over the past decade, Amherst has deepened its support of trans students. The College offers legal and financial assistance for the transition and name-change processes, for example, and the student health insurance plan covers hormone replacement therapy and gender affirmation surgery. Many trans and nonbinary students have participated in College support groups, the first one founded by Deardorff. And Moore Dorm includes the Sylvia Rivera Floor, a living space for LGBTQ+ students, named for the Stonewall trans icon. In short, community is being fortified here.

Johnson also tried to build community, both off campus and on. She attended some of the early Student Homophile League dances at UMass, for instance, plus social events at a fledgling gay commune in Northampton. In 1972, she helped organize Amherst’s first gay-friendly event, a “coming-out party,” at Valentine. She and her fellow hosts sent invitations “to people that they thought were gay,” recalls McCray, with a laugh. “It made people very, very nervous.” She also invited then-president John William Ward, who attended the party, as did several faculty members, “as an acknowledgement of support for those who were grappling with their sexuality,” says McCray. Johnson herself brought her boyfriend from UMass.

Johnson wrote in 1973 to “my closeted gay brothers and sisters” among the Amherst students and faculty: “I say, just remain there. ... You wouldn’t want to face it.”

During her senior year, she made a splash at the Sock Hop, Amherst’s biggest annual party. “She wore this purple floor-length gown with a single silver shoulder strap,” recalls Lenox. “She had on this ginormous Afro wig. The Student devoted an article to the Sock Hop afterward, and there was this throwaway line, something to the effect of, ‘Who was that stunning beauty in the Afro wig and the purple gown?’”

I asked, Were they kidding? Did they know this “stunning beauty” was their classmate? Lenox answered exultantly: “They didn’t know it was Tamara at all!” Such a choice detail. But I was frustratingly awash in details while missing most of the canvas and frame. In a magazine feature, the narrative often centers on someone’s career—but many careers were closed to trans folks in Johnson’s time. I knew she had worked at a music store in Munich, but not what she did, and not which store. I’d found her Amherst friends, but none from her post-college life in Europe, before or after her transition. The material was too thin. The stories of Black trans women have suffered so much erasure, and Professor Polk and I were fierce about reversing this trend. Yet doors just kept gusting shut.

Could family members help fill in gaps? Unlike the relatives of many trans men and women, the Johnsons had accepted Tamara, though there was a rocky adjustment period, says Culton, who describes her father as “very traditional.” But there was nuance here: “Her father was just extraordinary,” says McCray. “After her transition, he was very protective, and wanted to make sure that she was safe,” and insisted on picking her up and dropping her off when she was back in New York. McCray adds: “Tamara told me that he said to her, ‘You are a beautiful woman.’” Both her parents have died, and Johnson is such a common name that it was devilish to locate her siblings. I left an explanatory voice mail for someone who may have been her brother, but he never called back.

In the 1990s, Johnson’s Amherst friends had met her partner, a German musician named Florian, several times, when the couple visited her family and friends in the U.S. They were happy to see that he made her happy. Johnson had sent McCray a letter after her transition, as the relationship with Florian bloomed: “Strength and support are all along my path,” she wrote. “And I am rejoicing in life’s beauty.” But no one knew how to reach Florian now. I found a website for someone who seemed to be him, but the listed phone number didn’t work. I tracked down some possible former bandmates, plus the manager of a club where they played. My emails were in English and, through Google translate, German. Each lead fizzled out.

Man muss die Dinge nehmen, wie sie kommen, goes the German proverb. “You have to take things the way they come.” I couldn’t find Florian, nor any European friend, co-worker or boss, nothing—but Polk had a thought. He put me in touch with a friend of his based in Munich, a New York University historian named Sasha Disko, who has written about, among other topics, gender shifts during the Weimar Republic. She was intrepid: She walked to the street address on the musician’s website. Nothing there. She guessed that the music store was probably the hundred-year-old Bauer & Hieber branch and talked, in person, to a clerk at their front desk. No help. Disko suggested I write the store manager—and finally we got a source, a former employee the manager recommended.

This retired Bavarian woman, Annemarie Wimmer, agreed to speak to Disko in German, and I drew up a list of questions. It turns out that Wimmer was Johnson’s best friend at work—and, for a long time, the only one there who knew about her plans to transition.

One day in the late 1970s, inside a brick building on Munich’s Landschaftstraße adorned with a large musical clef symbol, Wimmer, a salesperson, left her post upstairs and headed to the basement. That’s where Johnson labored as a warehouse clerk, sorting, selecting and ordering sheet music. The friends often had little chats here, and on this day Wimmer felt dejected: “I remember I was saying that I was so sick of being a woman and that it would be so much easier being a man. Tamara looked at me and said: ‘That’s not how I feel.’” And then Johnson told Wimmer about her plan.

Wimmer witnessed that plan unfold. “Tamara had to go through a whole battery of tests, psychological and physical,” she says. “She had to go to so many doctor’s appointments, over years! And then she had the procedure at the hospital Klinikum Großhadern.

Johnson had packed up her apartment beforehand, McCray told me; her friends moved everything to a new apartment so that she could start fresh, after she left the hospital, in a different neighborhood. Wimmer visited Johnson at the hospital after the surgery: “She was just glowing! She was so happy. I will never forget how happy she was.”

Wimmer was not part of the LGBTQ scene in Munich and didn’t know much about that part of Johnson’s life. But the two shared a love of Maria Callas and went together to concerts by Diana Ross and Gladys Knight & the Pips. Johnson kept a harp in her tiny apartment and, on Sundays, played organ at an American church in Schwabing. “Her piano playing was phenomenal,” says Wimmer. “She could hear a song once and play it by ear in the right key.” Wimmer also marvels at her friend’s ear for languages: Johnson had picked up Bavarian and loved to show it off for the woman she called her bayrisches Mädel, her Bavarian friend. Says Wimmer: “You see, Tamara was such a linguistic genius she could even speak in dialect!”

A word about Johnson’s job status: A 2021 McKinsey report reveals that American transgender adults are twice as likely as cis adults to be unemployed. They make a third less income than cisgender adults, with more than half of trans adults saying they are uncomfortable being out at work. Take these recent stats and shoot back 40 years to when the American Psychiatric Association labeled trans people as having a disorder, and you can see what Johnson was up against in trying to make a living, even if Germany was more socially liberal.

Says Wimmer: “I always thought, ‘What is she doing down there in the basement? She’s too intelligent for her job.’ She was a great worker and didn’t just do her job but really thought about things and how to do them better.”

You could argue that management preferred to keep Johnson in the basement, hidden from the public. But there are subtleties to this story. Germany was perhaps more accepting of trans people than America, seeing as it was the first country to offer gender affirmation surgery, thanks to the surgeon Magnus Hirschfeld, who founded Berlin’s Institute of Sex Research in 1919. (It was burned down by the Nazis.) And Wimmer indicates that this Bauer & Hieber branch had a culture of tolerance. There were a number of Black employees besides Johnson, and the manager was a decent man. As Wimmer recalls: “Mr. Muthmann assembled all the store employees and informed them of Tamara’s decision and told them that she had his complete support and that he never wanted to hear any bad talk about Tamara or have her complain that she didn’t feel accepted.”

But offensive comments came her way nonetheless—and the person who drew the line at Amherst did so here, too. Says Wimmer, “Tamara wouldn’t allow people to tease her or insult her; she could defend herself. She admonished or warned people, but she never got loud, yelled or cursed. She was very optimistic, charming, very charismatic. She was well-respected and liked and was very self-confident. She was very courageous. And she was so nice that you just had to like her. She was both a very interesting person and a very interested person. And if you had problems or heartaches, she was a great listener. She was really like a ray of sunshine.”

When I delicately asked her Amherst friends how Johnson died, they at first declined to tell me. “I can’t talk about it,” said McCray, choking up. “I truly want to make sure that her legacy is one of celebration.” All three friends used the phrase “chronic illness,” but when that term is applied to a gay or trans person in the 1980s and 1990s, you can’t help but wonder if it’s a euphemism for AIDS. In fact, Wimmer speculates that Johnson contracted AIDS from her surgeries, but she has no proof.

Several days after I spoke to McCray, Lenox and Culton, they decided to go on the record about the circumstances of Johnson’s death and that Culton would deliver the news.

He told me that she was chronically ill and so made the decision to end her life.

The principal reason had to do with Florian, says Culton. “She was trying to not put him through an agonizing and drawn-out illness. Because it was only a matter of time.”

Mindful of the “tragic trans” trope, I wrestled with how to share this truth, to pay tribute without diminishing her. Honestly, this whole reporting experience had become personal, and not just for me. In the process of our research, Khary Polk, Sasha Disko and I—two professors and a journalist—had come to care so much about this trailblazing woman whom every single person I talked to called “courageous.” The three of us formed a sort of support group, chasing leads together, troubleshooting as obstacle after obstacle presented itself. It was like we owed Johnson. We owed it to her to fuse our skills with our commitment, making it a mission, doing the best we could with what we had.

And isn’t that what Tamara Johnson did, too? What she could do was limited, given the times she lived in. What she had—her character, her strength, her vision for her future—was profound. And her best was something to behold. She consistently lived her life in the way she chose, no matter how hard it was, right through to the end. So her manner of death was as unswerving as her life.

In our email chain, Disko wished we could find Johnson’s gravesite, if she had one. “Because I would bring flowers and light a candle and sing her a song,” she wrote. “Or rather, I’d sing a song with her.”

It was a beautiful funeral service, recalls Wimmer—so full of people, with gospel singers there to perform in homage. “The mood was one of both sorrow and hope. We were all crushed that she had died, but it was also a celebration of her life.”

I may never have found Florian, but McCray sent me a copy of his eulogy. It soars. Florian said that Johnson was a truly spiritual person, brave, singular. He spoke of “her strength to confront honestly and continuously all the weaknesses inherent in mankind, therefore letting the weaknesses become strengths.” And he spoke of “her ability to look behind those unimportant things as religion, race, as well as sex” to discover the core of a human being.

Florian also quoted his mother, who, in the raw weeks after Johnson died, tried to comfort her son with these words: “A phenomenon like Tamara can only be a gift for a certain time.”

And then he tried to get at the quintessence of Tamara Johnson, who journeyed from Queens to Amherst to Paris to Munich to follow her remarkable life’s music and become the person she was. “The humanity of Tamara,” he said, “was characterized by two of the most positive human qualities: clarity and love, both in their purest forms.”

*This sentence has been changed from the original to correct the name of the classmate who also studied in France that year.

Katharine Whittemore is Amherst magazine’s senior editor.