Death is the only inevitable event in life. And yet, nothing is more heartbreaking than the death of a young person who has just come into their own and barely begun living. Nothing feels more unfair to me. And so, reading the first few chapters of Dustin Thao 18’s young adult novel You’ve Reached Sam was difficult. The story begins with Julie’s memories of the three years she spent with her boyfriend Sam, who has recently died in a car crash, two months before their high school graduation. So closely does Thao make us feel Julie’s devastation at the loss of Sam that I put aside the book for a week, unable to face this mundane tragedy of our lives. This is definitely a book that will make you cry.

Julie is spiraling. She has missed so much school and is so far behind that she may not be allowed to graduate. In fact, she has hardly left her bed since the accident, not even to attend Sam’s funeral. She blames herself for his death, and some of his friends do too. After all, it was she who Sam was driving to pick up at a bus stop when he died.

Julie’s guilt sends her running through the rain to visit his grave, but she doesn’t even know exactly where he is buried in the cemetery. Alone in the dark and desperate for forgiveness, she calls his phone number. Why? She doesn’t know. But her heart stills when someone picks up, and it’s Sam on the line.

Thao’s novel is a journey through the grief of a young person with an already tumultuous life: Julie’s parents are separated, she is displaced from her native Seattle, and she is suffering a deep crisis of identity. My first thought was that talking to and clinging to a dead boyfriend could not be good for the mental health of such a teen, but this is not really a novel about resurrecting the dead.

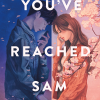

You’ve Reached Sam

By Dustin Thao ’18

Wednesday Books

Rather, it is a novel about learning how to balance remembering and cherishing our dead and letting them go. Julie struggles: she pushes people away, and her obsession with talking to Sam makes her unable to see how much she is hurting her living friends and family.

What I most admire about this novel is how Thao has managed to write a book that does not strain too hard at creating big, pivotal events. It is organized like grief, actually, with intense bursts of anger, guilt and sadness nestled within scenes of the everyday: going to school, doing homework, meeting with friends, worrying about college admissions. There is a gentle stillness here, and an invitation to recognize that recovery after a death is slow, simmering work.

Teens will engage strongly with this story, because it features themes that will resonate: the struggle between trying to fit in and being true to oneself, the discovery that one’s parents are fallible and human, high school bullying, self-discovery and the quest for identity, the big college decision, and examinations of friendship and romance. Adults, however, may find the book too soaked in angst and some plot points underdeveloped. For

example, while Julie’s mother is presented as paranoid, this never quite complicates the story. The story also sits so heavily with Julie’s grief that some scenes feel repetitive, and she hardly makes decisions or has agency. But the book was not written for adults and therefore does not need to cater to adult literary needs. It is crafted tenderly and thoughtfully. I believe it will move its audience.

Onjerika won the 2018 Caine Prize for African Writing, was shortlisted for the 2020 Bristol Prize and was a 2020 Best of the Net nominee. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Black Warrior Review, The Adroit Journal, Granta, The Johannesburg Review of Books, Fireside Quarterly, Wasafiri, New Daughters of Africa and elsewhere. She founded and teaches at the Nairobi Writing Academy.

Illustration by Hanna Barczyk