What inspired you to write this book?

I was in school, studying work by poets who were writing about real-world issues and who were doing qualitative research to inform their poetry. My professor opened my eyes by saying, “You don’t have to go to a library to do research; people are archives, too.” That got me thinking about my parents. When I was growing up, they would tell stories about their past in Burma. I wanted to access those stories before it was too late. So I invited my mother to continue her storytelling. I recorded our conversation—I think while I was massaging her feet—and translated it into Burmese, which was difficult, because I don’t actually write in Burmese, and I have no formal education in it. I took very little creative license: I directly transcribed and translated my mother’s words, then artfully arranged them into a narrative. The next semester, I read W.G. Sebald’s novel Austerlitz, which almost reads like documentary poetics or investigative reporting. I thought: What if I inserted myself into my mother’s stories, as a person to whom the stories are being told? I started writing, not word for word what my parents said, not word for word their stories, but my memories of growing up listening to them. That’s how the project began.

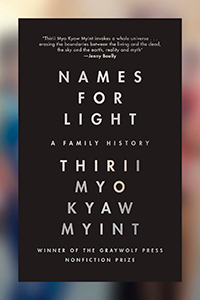

How did you choose Names for Light as the title?

The book ends in the present, or as close to the present as possible, after I have moved to Amherst, when I’m at MASS MoCA, at an exhibit on light. Earlier in the book, there is a revelation when I finally learn the name of my brother who passed away when he was a baby: His name meant “light.” For me, these two moments inform the title deeply. But I chose the title because so much of the book is about naming: naming of places, naming of people, the ways in which names change over time, based on whomever is in power. It felt right that the title would be a kind of paradox—that we’re trying to give names to light, which is something nobody can hold, nobody can see in the exact same way. That felt like what I was doing with the whole project.

Can you talk about how you balanced historical and political con-text with your parents’ stories?

You’re getting at the heart of my struggles in writing this book: I felt burdened with the responsibility of educating my readers about the historical context of my family history. In early drafts, I incorporated my external research and reading on the political events that impacted my family. But I quickly realized that I’m not a historian of Burmese history, and in the end, I included context only when my parents told it to me. I fact-checked what they told me, and

offered my commentary on it, but I did not include secondary sources. This has made the book quite different, perhaps, from what some people may expect it is. If you’re trying to learn about the history of Burma, this is not the book for you. If you’re trying to learn about the country’s recent politics, this is not the book for you, because it does not provide that information. Some readers may be disappointed in that. But I’m hoping people can still learn something from what’s in the book.

Your answer reminds me of a question that came up in our Asian American literature course: Do we need to educate or give cultural context to our readers? Should we?

Many of the writers who visited our class talked about how, earlier in their careers, they felt that same burden. As time passed, they started to feel differently. They realized that there are libraries, there is the internet. People can do their own research and find their own context.

How did you know when the book was complete?

Jem, I’m sorry to disappoint, but I still don’t feel done. I’m preparing for a reading tonight, and I was looking through the book trying to find a passage to read. I found myself editing as I went, thinking, “Oh, I shouldn’t have written that sentence.” So, for me, the work of writing and editing is never done. What is done is the publishing process: It is a time capsule, the moment when the project was halted and made into a book. But is the project itself ever done? I should hope not, because I think that would mean I wouldn’t want to write anymore. The thing that keeps me going, that makes me want to keep writing, is the feeling that I’m not done, that I have more to say, more to revise and more to explore.

Do you have advice for younger writers?

I honestly feel that younger writers should be the ones giving me advice, because I want to stay relevant. Advice I would give to myself when I was younger, starting out, is to not compare myself to anybody. Obviously, it is very difficult to accomplish that. I have heard writers say that rejection can be motivating, and envy can be motivating, that feeling the need to prove oneself to others can be motivating. But, for me, that sort of writing—writing that’s coming from a place of insecurity—never feels good. It may become polished, it may become prizewinning, but it’s not nurturing for the soul. I don’t think it’s a good place for art to grow from.

This reminds me of the saying, “Comparison is the thief of joy.”

It’s so easy to support other writers, to shout out people and to focus on the good. I don’t use social media anymore, but when I did, I surrounded myself with writers I admired and respected. I did not allow myself to hate-follow anyone or to stalk anyone who wasn’t a true friend or colleague. It was good for my mental health, because, actually, it’s just as easy to draw inspiration from other people as it is to feel insecure because of other people.

I agree! Amherst has phenomenal writers, so I always want to read more of my friends’ and classmates’ writing. The discussions from our Asian American literature course were also amazing: Every class, I just wanted to listen and absorb everything that was said.

I was so impressed by the ways in which you all came together as a community to support one another. I haven’t felt a sense of competition in Amherst classes at all; everyone is very affirming of each other’s opinions and ideas. There seems to be a sense of collaboration and excitement to be working together. For me, that’s been motivating and inspiring.

Jem Park ’22, an English and statistics major, served as president of the Asian American Writers’ Group on campus and as department head of creative writing and arts for The Stream Magazine. She’s still searching for future plans, but in the meantime, she enjoys taking walks on local trails and reading at cafés.

Photographs by Leah Fasten