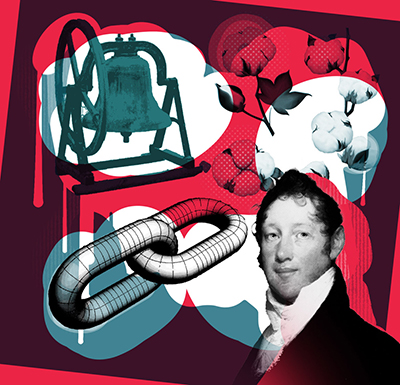

This statement was the foundational point of my senior thesis in American studies in 2022. My thesis research began with a man I first learned about through a campaign by Amherst’s Black Student Union. Israel Trask, an Amherst trustee from 1821 until his death in 1835, was born in Massachusetts but had gone to Mississippi and Louisiana to amass a fortune through enslaving more than 250 men, women and children—a fortune he later used to assist in the founding of the College I had come to love. In a way, his geographical path mirrored my own as I navigated between North and South, between Amherst and my home state of South Carolina.

In addition to his role in the College’s founding, Trask left $300 to Amherst in his will. It was collected by the College’s treasurer, Edward Dickinson, Emily Dickinson’s father. Years earlier, Trask and Emily’s maternal grandfather, Joel Norcross, had crossed paths in their contributions to Monson Academy, a nearby prep school.

I left those connections as a single, unresolved footnote in my thesis; they weren’t my focus. Instead, I traveled across the South and interviewed Nicka Sewell-Smith, a descendant of people enslaved by Trask. I investigated the ties between Trask and the College. I sought to highlight the lives of the enslaved people he brought to Massachusetts.

Dickinson and Norcross faded into the shadows. After all, could the Belle of Amherst really be connected to the economy of enslavement?

Anna Smith ’22 works for the podcast The Slave Is Gone, about the Apple TV+ show Dickinson.

But something kept pulling me back to that question, even months after I graduated. So when my thesis adviser, Professor Karen Sánchez-Eppler, contacted me about an opportunity to do research for The Slave Is Gone, a podcast about the Apple TV+ show Dickinson, I jumped at the chance. There is a scene in the first season of the TV show where Emily and friends are discussing the impending Civil War. “It would be economically devastating for everyone,” one character says, wearing a cotton nightgown.

This fall, I became a researcher for the podcast, which is hosted by the poets Jericho Brown and Brionne Janae. My first task was to identify any economic ties to slavery in Emily’s family. I learned that Norcross had purchased Trask’s Brimfield, Mass., cotton factory from him in 1816. Then I found out that Emily’s paternal grandfather, Samuel Fowler Dickinson, was a partner in the Amherst Cotton Factory. Here, the cotton came from South Carolina—my home state.

What is clear is that the family’s wealth was intimately connected to the lives of enslaved individuals. It is also clear that Amherst College was financially supported by not just one but multiple people who supported the economy of enslavement, all while educating Black students such as Edward Jones, class of 1826.

Today, in my ongoing research for the podcast, I continue to seek out information, not only about the Dickinsons and their peers but also about the people who made their lifestyles and poetic endeavors possible. My aim is not to suggest that we stop celebrating Dickinson’s poetry because her family accumulated wealth from enslaved labor, but rather to shed light on that fact and understand her life in the context of it. Trask and the Dickinsons navigated a world of contradictions. Now, in my first job after college, connections and contradictions have become my specialty.

Illustration by Andy Martin

Photo by Patrick Montero