Coming Together at the Seams

By Josh Fischel ’00

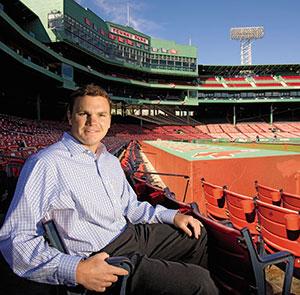

Ben Cherington ’96 works at the epicenter of one of the fiercest rivalries in all of sport, in arguably the most rabid baseball town in America. Here is how a former Amherst pitcher became an integral piece of the Red Sox machine.

One advantage to working for the Boston Red Sox is that when you go to the office after a particularly brutal loss, there are no Yankees fans waiting by the water cooler to taunt you. The downside is, the loss might have been because of something you did.

A sunny day at the end of August last year found the Red Sox finishing off a horrendous month of baseball. The team had gone 9-21—including a five-game sweep at home at the hands of those rival New York Yankees—and had endured a sky-is-falling spate of injuries: pitcher Curt Schilling, catcher Jason Varitek, shortstop Alex Gonzalez and outfielders Trot Nixon, Wily Mo Pena and Manny Ramirez were all out. David Ortiz, the designated hitter, was in the hospital for heart palpitations. Later that day, pitcher Jon Lester would be diagnosed with lymphoma.

Ben Cherington ’96 was maintaining a brave face while sitting two rows behind the dugout on the first-base side of LeLacheur Park in Lowell, Mass., home of the Spinners, one of Boston’s single-A affiliates. Cherington was watching four players kneeling in a line between second and third base, taking grounders hit to them by a coach kneeling near the pitcher’s mound. Two more players were lofting a football across the outfield. Later, there would be batting practice, though no one managed to tag the giant carton of Hood milk perched above the wall in dead center, 400 feet straight out. Everyone on the field seemed young, but more than that, they seemed merely life-size, a few layers of baseball away from iconic status.

Cherington was there to watch the pre-game routine: “We want to see that the players are practicing with a purpose.” He also used the time to talk informally with players, and to catch up with coaches and staff, for whom he seemed to have a real affection.

Cherington, a varsity pitcher at Amherst, joined the Red Sox organization in 1998 as a scout, and eventually became director of player development, overseeing players from the time they signed through their years in the minor leagues. Then, in October 2005, after general manager Theo Epstein unexpectedly walked away from the club, the Red Sox named Cherington as co-general manager, along with Jed Hoyer, a 1996 Wesleyan graduate. Forty-four days later, Epstein returned in more or less the same capacity, and Cherington was reassigned to the position of vice president and director of player personnel, a job that now puts him in charge of domestic and international scouting as well as player development.

Beyond front office upheaval, there has been plenty of recent ado on Yawkey Way in Boston. In 2004, the team won its first World Series since 1918. Following that magical season, there was the inevitable shift away from the championship roster, due to age, expiring contracts, free agency and the need to improve. Pitchers Pedro Martinez and Derek Lowe left, as did shortstop Orlando Cabrera and outfielder Dave Roberts, among others. By the next off-season, that transition had shifted into a dismantling. Other than Jason Varitek, no infield starters from 2005 were with the team in 2006. Just before Cherington’s promotion to GM, but after Epstein’s departure, the club acquired starting pitcher Josh Beckett and third baseman Mike Lowell. Before Christmas in 2005, two weeks after Cherington and Hoyer became co-general managers, center fielder Johnny Damon signed with the Yankees in a move that seemed to surprise the front office as much as it did Red Sox Nation. Damon had been the exuberant face of the team and had once told a reporter that he could never see himself playing for the Yankees. Now that New York had taken Boston’s most marketable player, grumbling began.

Coupled with reports that co-owner Larry Lucchino was meddling in baseball operations, the loss of Damon led some journalists and bloggers to question just who was running the show in Epstein’s absence. Persnickety Boston Globe columnist Dan Shaughnessy wrote that Cherington and Hoyer “can spin this any way they want, but Sox fans can’t escape the conclusion that there’s chaos at the top.” At that year’s winter meetings, a frantic period of signing and trading, the Red Sox were represented by not only Cherington and Hoyer but also the “Gang of Four,” which included veteran officials Craig Shipley and Bill Lajoie. The team made two good trades, acquiring second baseman Mark Loretta and center fielder Coco Crisp, but still the public sensed uncertainty in the leadership.

Seth Mnookin, author of Feeding the Monster, a behind-the-scenes look at the Red Sox, insisted, in an e-mail interview for this article, that “Cherington and Hoyer are extremely well-respected within the organization. When they were named co-GMs—and the original plan was to name them interim GMs, but somehow that got left off their titles—they both knew that Theo would be coming back to the organization; indeed, they’d been in almost constant contact with him.” Cherington backs up that assertion: “I don’t think either of us would have taken that job if we didn’t see the momentum building toward Theo coming back. As much as both of us want to be a GM, that wasn’t the time and place to do it.”

When I spoke with Cherington in Lowell, his voice was even and his expression serene. He answered my questions neatly and politely. That may be the result of professional media training—or his marriage to ESPN reporter Wendi Nix—but more likely it’s just his nature. Amherst baseball coach Bill Thurston remembers that even as a college student, Cherington was reserved; he seemed older than his years. “He doesn’t try to get in the limelight at all, and he doesn’t volunteer a lot,” Thurston says. The coach recalls a team trip to Florida, when Cherington roomed with the assistant coach. “After three days,” Thurston says, “my assistant coach asked me, ‘How old is Ben—35?’ He was 22 at the time.”

This attribute is particularly notable given the youth of Boston’s baseball operations staff: Cherington is 32. Hoyer and Epstein are each 33; vice president and international scout Craig Shipley is just a decade older. Mike Hazen, director of player development, is 31. The front office seems to realize that the average age of its staff can make it susceptible to criticism. Last fall, when New England Cable News reporter Jim Braude interviewed Theo Epstein, I noticed that Epstein and Cherington take a similar approach to answering questions: they’re practiced, a little tense, serious. Braude asked, “Can we talk about me for a minute here? What do you think is gonna come first: are the seats [at Fenway] gonna get large enough for my girth, or am I gonna have enough self-discipline to make sure that my girth contracts so that I can fit in the seat?” The camera showed Epstein pursing his lips. “I have no idea,” he replied. “I’m very uncomfortable with you talking about your girth.” As young executives, perhaps Epstein and Cherington are wary of coming across as clownish or juvenile. Instead, Braude ended up looking awkward: the older man trying to prove he could be hip with the kids.

The average age of baseball executives has gotten dramatically lower over the past several years. Eight American League general managers were born in 1964 or later. Cherington attributes the trend chiefly to the job’s heavy time demand. “There are budgeting, payroll issues, different contractual issues—a lot that perhaps GMs didn’t have to deal with 30 years ago,” he says. The hours do seem to be endless: Epstein and Hoyer spent one Thanksgiving, for example, wooing Curt Schilling at his home in Phoenix. At one time there were more retired players in baseball front offices. “If you’re a major league player,” Cherington says, “and you’ve had a successful career—in today’s game, you’ve probably done pretty well financially, too—the prospect of going back and spending 15 hours a day in an office at a very reduced salary may not be that appealing. Guys like me who grew up loving the game and not being good enough to play in the major leagues, we want to figure out a way to stay involved, and are willing to do anything to do that.”

Cherington earned credibility by asking questions and being deferential. “One thing about working with major league players: if you played through college, you might as well have played through Little League,” he says. “You’re either a professional athlete or you’re not.”

Cherington arrived at Amherst from Lebanon High School in Lebanon, N.H., where his coach, Chuck Hunnewell, remembers him as “our number-one pitcher at Lebanon, our number-one stopper in American Legion.” Cherington continued to pitch during his first two years at Amherst, until he hurt his shoulder in the winter of his junior year. What he had thought was tendonitis turned out to be a labrum tear. “The surgery didn’t take,” says Thurston, “so he pitched in pain during his junior year until we shut him down.” Instead of playing, Cherington became a pitching coach his senior year. He stayed on as a pitching coach for a year after his graduation while pursuing a master’s degree in sports management at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. During that time, Thurston gave Cherington’s name to Dan Duquette ’80, then general manager of the Red Sox, who was looking to fill an opening in player development.

Amherst alumni have been influencing baseball management since the illustrious career of Harry Dalton ’50, who is credited with assembling the Baltimore Orioles team that won the World Series title in 1970. “He’s the one that got Duquette started,” Thurston says. Dalton served as general manager of the Orioles, the Los Angeles Angels and the Milwaukee Brewers. He died in 2006, and a new top for the Amherst field is being laid in his name.

Amherst has arguably had more success in graduating its players to front-office and scouting positions than onto the field. Dave Jauss ’80 is a bench coach for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Tom Bourque ’80 is a scout with the Chicago Cubs. Neal Huntington ’91 is assistant general manager for the Cleveland Indians. John Couture ’92 works with the Indians as a sports psychologist. And Duquette preceded Epstein as Boston’s general manager. At least 16 former Amherst players are now working in Major League Baseball. Several of them coached under Thurston, with the help of Hitchcock Fellowships, before they found footholds in professional baseball. The pipeline continues to function: Duncan Webb ’04 served as a pitching coach at Amherst. His fluency in Spanish and knowledge of the game led Cherington, on Thurston’s recommendation, to send Webb to coach at a Red Sox academy in the Dominican Republic; Webb now works full-time in player development for Boston.

“There are some things that Coach Thurston knows, particularly about pitching and the biomechanics of the pitching delivery, that are as good as any pitching coach in professional baseball,” Cherington says. The Red Sox have incorporated some of Thurston’s teachings, too. “The standard he sets is something that rubbed off on me,” Cherington says, “and is something that we try to replicate here.”

Besides the networking and the teaching, Thurston attributes Amherst’s strong presence in the ranks of baseball management to his program’s focus both on the concepts of the game and on instruction. He recruits kids who love to play but who aren’t necessarily the most proficient.

That is Thurston’s luxury, but it is certainly not Cherington’s. Drafting and developing professional players who simply love the game will not win you many championships. The scouts whom Cherington hires to scour high school and college games must evaluate players based not only on statistics but also on observation—how an outfielder breaks for a fly ball, for example. “One of the ways we’re trying to exploit the market,” Cherington says, “is by figuring out a way to blend the use of traditional evaluation with the use of performance indicators in the most efficient way.”

The approach of looking at non-traditional statistics (on-base percentage, for instance, instead of batting average) became widely known through Moneyball, a 2001 book about the Oakland A’s. “It’s hard to argue with the success they’ve had on a pretty consistent basis” and on a relatively tight budget, Cherington says. Still, Cherington is careful not to lump the Red Sox’s strategy together with Oakland’s. In Moneyball, Oakland GM Billy Beane largely drafted players out of college, partly because he thought their numbers were more likely to be indicative of professional success; the Red Sox did the same in 2003 and 2004, but “the last two drafts have been more of a mix. We don’t set out to take college or high school players,” explains Cherington. “We set out to take the best player at the time we’re picking.”

Regardless of tactical shifts, the Red Sox have had strong drafts for the past several years. Baseball America ranked the team’s 2006 picks the best of any team: “After depleting their system through call-ups and trades, the Red Sox took a big step toward restocking it with this draft.” Recent results from minor league call-ups, however, have been mixed. Last season, several of the most highly touted prospects in the Red Sox farm system, including relievers Craig Hansen and Manny Delcarmen and infielder Dustin Pedroia, struggled in the major leagues. “Until they’re in that environment of Boston,” Cherington says, “playing for a major league team, playing in front of 45,000, playing in meaningful games, you just don’t know how they’re gonna react.”

If there’s no way to predict a minor league player’s success in the bigs, there is, at least, a system in place to support his growth. John Couture, the sports psychologist with the Cleveland Indians, says that “most organizations have some form of player development in the mental domain. A few, such as us and the Red Sox, have professionals on staff to implement a system of mental training or development.” The Indians’ system is scientifically based, but when coaches are determining whether to move up a minor league player, the decision seems to lean on individual observation. Still, baseball is a business, and “sometimes, the player’s talent is needed before his mental skills have been fully developed,” Couture says.

Another part of the business is deciding whether to fill a major league opening with minor league talent or with a tested veteran. In the off-season following the 2004 World Series win, the Red Sox had a hole at shortstop. Hanley Ramirez, who was playing for the Sox in the minors, “wasn’t quite ready for the big leagues,” Cherington says, “but he wasn’t far away, either.” When the Sox signed Edgar Renteria to a four-year contract, Cherington explained to Ramirez that the team had a more immediate need than Ramirez could provide, and that Renteria was the best player available. “We spend a lot of time talking to our minor league players about what they can control and what they can’t control,” Cherington says.

As it happens, Renteria was traded away the following off-season, and Ramirez was shipped off in the Josh Beckett deal to the Florida Marlins, where Ramirez became last season’s National League Rookie of the Year. That sort of thing must be frustrating to a manager in charge of player development, but Cherington shows little seller’s remorse. “We’ve traded some good players,” he acknowledges. “We knew those guys were going to be good players. We want to see them do well. We ultimately want to see the Red Sox do well, too.”

Cherington’s calm even-handedness concerned me a little. He works at the epicenter of one of the fiercest rivalries in all of sport, in arguably the most rabid baseball town in America. He was raised a Red Sox fan. Of the 1986 World Series, in which Boston was a single out away from defeating the New York Mets before Red Sox first baseman Bill Buckner allowed a grounder to dribble agonizingly between his legs, Cherington says, “The day after Game 6 was the only day my parents let me skip school without being sick.” Yet he maintains an objective, politic demeanor about the Yankees: “I have a great respect for the rivalry, and there’s probably not a team I’d rather beat more, but I don’t have any contempt for them, because a lot of the players on their team, we respect. That extends to the front office—it’s hard not to respect Brian Cashman. He’s a great guy, he works extremely hard, he’s fair to deal with, he’s honest.”

And then it appears, finally. “At the same time,” Cherington admits, “I would say there’s less camaraderie between the front offices than there might be between us and other front offices. When we’re at the winter meetings, you don’t really see Sox executives hanging out with Yankee executives.”

Rivalries are funny things, and Cherington and I share three of them. We’re on the same side of two—Sox-Yankees and Amherst-Williams—but he went to Lebanon High in western New Hampshire, while I attended Hanover High School in the next town to the north. “There are a lot of similarities between Amherst and Williams,” Cherington contends. “It’s a bunch of smart people going to school on pretty campuses. You go to an Amherst-Williams football game and there are many generations of people on both sides who are so passionate. Although it’s intense, it’s collegial in a way—people care about it, but it’s not life and death.”

Our high school rivalry is different. It’s fierce because it’s so tied to identity. “I remember thinking of Hanover as sort of the elite,” Cherington says. “We’re the blue-collar guys going off and trying to beat the white-collar boys from Hanover, riding around in their Mercedes. These guys have more than us, they’re the rich town, they get everything they want, but we’re going to beat them on the field.” Hanover folks tend to see the disparity between the two towns as one of enlightenment versus dimness. Hanover is home to Dartmouth College; Lebanon to strip malls. A few years ago, Hanover fans started mockingly wearing orange hunting hats to Hanover-Lebanon soccer games. The practice has since stopped, and the rivalry has become healthier, but only because it got kind of ugly first.

The Sox-Yankees rivalry is also distinct. It’s geographic, too, but, more than that, it’s a struggle between the perennial underdog and the habitual powerhouse. When the Yankees win, Boston fans gripe that Yankees owner George Steinbrenner bought another championship, and that the championship can’t mean as much to New York. The Yankees have 26 World Series rings—after a while, it must become kind of rote. “It cuts right to the core with a lot of people, and it goes on for six months,” Cherington says. “Even when we’re not playing the Yankees during the regular season, fans and the media are always looking ahead to the Yankees series. If we do play them in the playoffs, that only adds to the intensity. So the big difference is that it’s omnipresent. With Lebanon-Hanover, we’re playing each other, but it’s in different sports, the teams are different, we only play each other a couple times. Amherst-Williams, same thing. Yankees-Red Sox is always on the forefront of people’s minds, from the time the season starts to the time it ends.”

School teams, of course, have frequent turnover on their rosters, but they don’t have widespread free agency. Players do not defect from Hanover to Lebanon or from Amherst to Williams. Professional free agency can complicate matters. What happens when your favorite player stops playing for your favorite team? Just who are we rooting for when we root for a professional team? Cherington offers, “I think we’re rooting for the collective hard work of players and staff and coaches and trainers and everyone, for there to be a tangible result. That was the feeling in the clubhouse after we won Game 7 in New York a couple years ago, that it was less about, ‘Thank God we beat the Evil Empire.’ It really felt more about, ‘There are all these people in here, players specifically and most importantly, who’ve worked so hard and battled so much, and put so much on the line, and what a great feeling to see it come together in success.’”

But some players have landed in Boston through the draft or in a trade or free-agent signing, not because they’ve always been Red Sox fans. Has free agency lessened the significance of the rivalry among players? Cherington doesn’t think so. “Walking around the clubhouse before a Yankees game, even in April,” he says, is not at all the same as “walking in there before a Devil Rays game.” Still, explaining to a new player what it’s like to grow up a Red Sox fan—the late summer fade, the love-hate relationship with Fenway, the perfection of Pedro, the frustration of those single moments that stole victory from us—must seem at times like trying to draw honor in Pictionary, or like trying to describe what colors are to a blind man.

John Couture allows that for the players, “the rivalries occur between teams that are fighting for the same playoff spot, or between pitchers and hitters who face each other often.” Match-ups in baseball are much more individual than those in other team sports, so it’s easy to dwell on each encounter and the resulting statistics as a measure of self-worth. The introspection could drive a player crazy. “As long as the player understands that each pitch is just that, and his routine stays the same, then he will thrive on the rivalry,” Couture believes.

Today, as Cherington helps the Red Sox in another season, hoping it will end more happily than last year’s, he allows himself some levity. Asked whether it is more satisfying to beat the Yankees because George Steinbrenner went to Williams, Cherington offers a smile—a small one. “It’s definitely not part of the pursuit,” he says, “but it’s probably a little more icing on the cake."

Josh Fischel ’00 received a master’s degree from the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan in the spring. He has written for The Believer and Bean Soup.

Photos: Samuel Masinter '04