The Song of the Caravan

By Rebecca Binder '02

For centuries, the Silk Road tied Asia together and created an astonishing cultural exchange. But the exchange disappeared with the silk trade, and rich traditions were largely lost. Today, in a groundbreaking project, ethnomusicologist Ted Levin ’73 is reviving the cultural treasures of the Silk Road and using music to again tie all the countries of Asia together. |

I’m walking into downtown Amherst with Ted Levin '73, and I’m having trouble keeping up with him and simultaneously managing the breath to maintain conversation. One of Levin’s long strides easily engulfs two of mine. Levin seems accustomed to walking for utilitarian reasons: to get somewhere, to meet someone or to share something. His jaunty, purposeful steps seem suited to a bustling Uzbek city or an unforgiving Siberian outpost. It seems almost absurd to expect the gait that has relentlessly carried the ethnomusicologist through Europe, Asia and the vast, shrouded Central Asian corridor between the two to navigate the tame streets of a college town.

But my guilt is unnecessary; Levin is comfortable here. Over the past 30 years, he has moved in and out of academia, settling finally at Dartmouth College, where he is an associate professor of music and a well-respected authority in ethnomusicology. He also returned to Amherst in 1998 as a visiting associate professor in the music department. Where Levin pulls away from the pack of academics is in his contributions back to, and advocacy for, the musical cultures he studies. Levin ponders over how to categorize his work; he likes to describe himself as “an activist-scholar.” Since 1998 Levin has been a vital administrative force at the Silk Road Project, a wide-ranging multidisciplinary initiative spearheaded by celebrated cellist Yo-Yo Ma. The Silk Road Project explores cross-cultural influences among the lands comprising the Silk Road and the West. The effort takes its mission one step further, providing an opportunity for the music to find a place in contemporary culture.

|

“If you asked a dozen ethnomusicologists what ethnomusicology is, you’d get a dozen different answers,” Levin tells me. “It’s essentially the study of music in its relation to a cultural and a social context; as an aspect of culture.” We’ve reached our destination—a coffee shop in town—and mercifully, we’ve sat down. “People call me an ethnomusicologist,” Levin continued. “I’m not always comfortable with the ‘ology’ part of that, because I’m less interested in the scientific study of music than I am in the people angle, the social angle. So the work that I’ve done, starting when I was a student at Amherst, has really been that—it’s been an interest in music and exploring other kinds of musical thinking, some of which are very different from what we’re accustomed to here.”

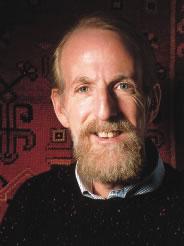

Physically, Levin is striking; his lanky body lends itself to a certain grace. He carries himself with an intelligent confidence that hints at both unpredictable adventure and staunch refinement; he seems equally capable of lecturing to a classroom of students and of exploring the corners of a distant city. To that, I would add a note on his eyes—they’re piercing blue—and a description of how he uses them: Levin captures the rare ability to look at several things at once. During our interview, as he focused on me, he was also taking stock of the cashier behind me and on what the customers next to us were drinking.

That quality must prove handy to his fieldwork. “Fieldwork is, to a large extent, hanging out with people,” Levin said. “It’s talking, and listening and watching. It’s observing.”

Levin began his fieldwork in Central Asia in 1977 while studying for a Ph.D. in music at Princeton University. He credits Amherst with germinating his interest. “When I came to Amherst I had already been interested in folk music, and I’d learned to play the banjo, the fiddle and some other instruments,” he recounted. “I had the good fortune to fall into the orbit of professor Henry Mishkin, who was then the chair of the music department. He was charmed by my interest in Celtic music, and he encouraged me to pursue it. And it was really thanks to his encouragement that I began to take this seriously,” Levin leaned towards me. “That it wasn’t just about being a banjo picker, that there was a way that you could study this music and look at its deeper implications.”

|

After graduating Amherst, Levin earned a Watson Fellowship, and spent a year traveling overland from Scotland and Ireland to India, sampling and studying music along the way. “I bought a car with my Watson money, and I drove across Europe to Ukraine and through the Caucasus Mountains on the Georgian Military Highway to Georgia and Armenia—it was nuts. But I loved it. I’m still following up the leads that I turned up that year,” he said. That was the first time I’d heard music from the Caucasus. And then I went to Afghanistan, and I spent a month there. That was my first view of Central Asia.”

“And that was the part of that whole swath between Ireland and India that somehow had the strongest tug on me,” he said. “It’s hard to explain—it wasn’t the music per se, although that was part of it. It was something to do with the geography. It’s beautiful. The wildness of the landscape, the ruggedness, the warmth and hospitality of the people; even the food somehow appealed to me.”

Inspired, Levin returned to Central Asia in 1977 and spent a year doing fieldwork for his dissertation, focusing his efforts on the shash maqam, the indigenous art-music repertory of Islamic Central Asia. The name shash maqam means “six modes”; but the term “mode” is more than just the scale that the term suggests in European music. The maqams are complex collections of song cycles, closer to the Indian concept of ragas than the European concept of Aeolian and Dorian or major and minor modes. The lyrics to the songs come from generations of Sufi poets and contain multiple layers of meaning, ranging from yearning for lost love to yearning for contact with God. The singing is intensely emotional against spare, stately instrumentation. The shash maqamwas the traditional music of the Islamic courts and had survived for centuries in Central Asia, but after the region came under Soviet influence in the decades following the Russian Revolution, all that changed. Shash maqam was seen as music for the feudal aristocracy rather than as music for the people, and was viewed as contrary to the ideals of the new Soviet culture. The shash maqam was never outlawed, but under Stalinist rule, performing ensembles were disbanded and the repertory fell under the pall of official contempt.

Beginning in the late 1950s, the shash maqam underwent a revival, but when Levin began his fieldwork, he found something he hadn’t expected. “To be honest,” he told me, “my initial impressions were that the shash maqam was a big bore. And it took me a long time to figure out why that was the case.” What Levin realized was that the music itself was not boring; rather, the performance style, dictated by Soviet policies, had “squeezed all the life out of the music. It had become ossified as a result of this cultural policy that sought to make of it a kind of museum exhibition. I discovered the tradition was very much alive, but not in the form in which it was being performed.”

“And so my experience, and what I tried to do in all the years I’ve been back, was to try and get beneath the surface,” Levin continued. “Try to get to the roots of that and to try to find the life, the spirit of innovation that made it what it was, which was great music. And in the course of that I found my way to performers that were not part of those ensembles I had heard in the 1970s, because they were not playing in a form that was acceptable. They were like dervishes in music, and they played this music in a way that was entirely different. When I heard it, I knew why this was at one time good music: there’s a kind of spirituality in it that made it come alive.”

“I was the first outsider to come study it as a musicologist,” Levin told me. “It was interesting because it was so important as a national cultural symbol and also because it had links to kinds of classical music in the Islamic world that form an arc of what you might call a great tradition in music that extends all the way from Morocco to China.”

Levin’s consequent work translated into his 1997 book, The Hundred Thousand Fools of God: Musical Travels in Central Asia (and Queens, New York). In his book, Levin uses music as a medium for chronicling social, governmental and political forces in Central Asia and shows how the use of music as a moral haven has endured despite powerful pressures from religious, communist and nationalist groups. David Reck, Amherst professor of music and Asian languages and civilizations, reviewed The Hundred Thousand Fools of God for the Summer 1997 issue of Amherst, calling it “far and away the best ethnomusicological book that I have ever read.” Reck added, “Levin is not only a first-rate, world-class scholar, but a mover and shaker, a man of action who truly believes that music lives through its musicians and its performances, and that contact between cultures can lead to mutual understanding and admiration.”

Yo-Yo Ma was similarly impressed by The Hundred Thousand Fools of God and asked Levin for his help in developing the Silk Road Project. “Ted’s such an unusual person in that he’s not only a great scholar and writer, but also a generous person in his field,” Ma told me during a telephone interview. “When we met, he was so ready to help. He’s been working in the area for 25 years, and he’s built up a certain amount of currency. He’s really a very trusted person, and he’s very committed.” Over the past three years, Levin has taken a leave from Dartmouth to work as executive director and curatorial director of the Silk Road Project. “Yo-Yo was very interested in the idea of the Silk Road,” Levin said. “He read my book and got in touch with me and asked me to help him. I was tremendously flattered.” Levin explained the underlying goal: “It’s finding a way for that music to circulate, to become a global presence, to become a part of the free cultural marketplace as a resource for innovation and for creativity; also, to insure that it’s appreciated in its own right, and to show that it has something to offer.”

The Silk Road Project finds metaphor in its focus, the historical trade route. From approximately 200 B.C. to A.D. 1400—a span of 1,600 years—Central Asia served as a vital corridor that at its height stretched from the Mediterranean to Japan. The trade artery connected what at the time was almost the entire known world, and the bustling network of caravan routes that cut their way through modern-day Turkey, Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia and China, among others, played host to a flurry of cross-cultural exchange. The intensity of that exchange in central Asia arguably has gone unmatched since 1500, when the plodding camel caravans finally were eclipsed by faster sea routes. The Silk Road facilitated trade of luxury goods: In addition to silk, products like textiles, ivory, and furs made their way from one end of the world to the other. Groundbreaking technologies—mathematics, the magnetic compass, the printing press and gunpowder—slowly crossed the Silk Road. The Silk Road also provided a medium for the transfer of ideas, changing the path of history: the venue brought previously isolated civilizations together for the first time. Along with pottery and foodstuffs, people exchanged ideas, philosophies, religions, art, literature—and music, culminating in Central Asia’s layered history and complicated musical tradition.

|

At its core, the Silk Road Project enables composers and performers from Asia, Europe and North America to interact, regard each other and engage in a transfer of ideas across cultural boundaries. Central to the project are a series of Silk Road Partner City Festivals, produced in cooperation with a few dozen partner cities across Europe, Asia and North America. Ma and the Silk Road Ensemble, a collective of international musicians, perform a program of works authentic to the lands of the Silk Road and inspired by the Partner City Festivals. A striking aspect of the Silk Road Ensemble’s performances are the way in which they force the audience to re-evaluate its own musical culture as it is introduced to unfamiliar ones. “Audiences hear music from the Silk Road lands played in an older form, and then they hear it stylized by a composer,” Levin explained. “It’s up to them to be the critic and to figure out, does this work? Is this a direction that has possibilities?”

Interest in the project and its mission picked up quickly. In June, the Silk Road Project and the Smithsonian Institution’s Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage coproduced the 2002 Smithsonian Folklife Festival, “The Silk Road: Connecting Cultures, Creating Trust.” The festival, held on the Washington Mall, was the first Smithsonian Folklife Festival dedicated to a single theme. The exhibition showcased music, art, food and crafts from 25 Silk Road countries, and drew 1.3 million visitors. Levin served as co-curator of the festival, and called it the culmination of his work. “I think everyone who came to that festival was touched,” he remembered. “We were doing this work long before September 11th, but there was a kind of urgency about it that wasn’t there before. People understood, as Yo-Yo said, that we could no longer afford not to know who our neighbors were, to know the cultures of Central Asia, and that was also the attitude of the State Department; they gave us a lot of support. I think it was also that feeling of breaking through the unfortunate stereotypes that were beginning to grow in this country about the Islamic world, and trying to give people a face-to-face experience.”

“Ted always works with the people he’s advocating for in mind,” said Ma, who summed up Levin’s contribution in one word: enormous. “He just wants to be as helpful as he can.” Levin left full-time work on the Silk Road Project in August. Since then he has continued to advise Ma and his colleagues as they plan a concert tour of Central Asia scheduled for April 2003. At the same time he has joined forces with the Silk Road Project’s major sponsor and key creative partner, the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, which has launched its own program, the Aga Khan Music Initiative in Central Asia. Levin is senior project consultant for the venture. A grassroots program to support musical tradition-bearers striving to transmit their knowledge to the next generation will be initiated in the Central Asian republics with the hope of reinvigorating indigenous musical cultures, Levin explained. “After the Soviet Union broke up, the system that had been in place there—and had worked quite successfully at bringing people together and creating a system of interchange—broke apart, and now there’s a very strong need to create points of contact for audiences and people interested in the arts. So our mission now is to help build a sustainable basis for this kind of music in Central Asia itself.”

Concurrent with his ongoing work in Central Asia, Levin has accepted a grant from the Ford Foundation to support work on the book he had begun when Ma recruited him for the Silk Road Project three years ago. “I believed I would wake up early in the morning and work on the book,” he chuckled, “but every waking moment was devoted to the project. I’ve been on leave from Dartmouth, and I have one more year of leave before I go back there.” The book is tentatively titled Where Rivers and Mountains Sing: Sound, Music and Nomadism in Tuva and Beyond. Levin’s focus is Tuva, a remote region in southern Siberia’s Altai mountain range, and its remarkable throat singers, who practice a technique where one singer can sing several notes at once. Levin brought Tuvan throat singers to Amherst during their first tour in 1993, and describes Tuva as “a musical Olduvai Gorge.”

“At root I’m writing about my idea that this music provides a window onto arguably the very origins of music, when it was used as a way of calling spirits, as a way of working with animals,” Levin said. “I got to know these musicians, and what I discovered was another world, a sort of music without performance, music as a way of communicating with nature, just a person standing there singing to a river, to a cliff, to a bird, and seeing what comes back. Tuvans are reverb freaks; they love to sit and hear the sound, the singing that comes back out of the steppe. So that’s led me to a radical new way of thinking about music.”

In a September 1999 article for Scientific American, Levin wrote that throat singing is tied to the Tuvans’ ancient notion of animism: the idea that natural objects and occurrences have souls or are connected to spirits. “And there again, there’s an understanding of music that’s totally different from the way we understand it here,” he told me. “It’s a way of communicating with spirits. They’re not very interested in melody, and not even so much in rhythm as they are in timbre. They imitate the sounds in the natural world, and thus, place themselves in the spirits of particular places and beings: of mountains, of rivers and animals. It’s music not as art, but as technology.”

In the end, Levin loves his work as much for the doors it has opened for him as for the results of his research and efforts. “Getting to know musicians and ways of musical thought in other parts of the world,” he said, “has for me provided a window into other cultures, other languages and other societies. It’s given me an opening into parts of the world that often are not always terribly open to outsiders, and I’m grateful for that.” He thought for a minute, and then continued. “I don’t really believe the cliché that music is an international language; I think it’s many languages. But when you learn a musical language, just as when you learn a different verbal language, it gives you entrée into a different world, and that has been the joy of doing this work.”

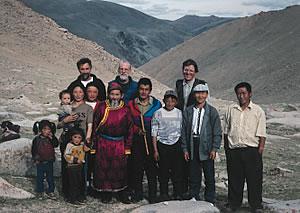

Photo of Narantsogt and his family: David Harrison

Photos of Qahhar Rahimov, landscape: Ted Levin

Photo of Ted Levin: Frank Ward