Blazing the Trail

Lewis on the front page of the Boston Journal on March 1, 1911, in an article announcing his nomination as an assistant attorney general. |

By Evan J. Albright

The son of former slaves, William Henry Lewis, Class of 1892, broke down racial barriers in football, politics and law. Today, his life story is surprisingly relevant.

Massachusetts inaugurated its first African-American governor early this year. The path that took Deval Patrick, the state’s new chief executive, to a corner office on Beacon Hill is the same one that another African-American—William Henry Lewis, Class of 1892—had blazed almost a century earlier. Both Patrick and Lewis sought education in Massachusetts to escape poverty. Each earned a Harvard law degree. Each became an assistant attorney general of the United States, and each went on to find success in the private sector. Patrick has made history in the Bay State, and it was Lewis who helped set the stage.

Lewis’s life has all the classic elements of the Horatio Alger stories popular in his youth: a poor and disadvantaged child, through pluck and luck, finds success and fame. During much of his lifetime, Lewis was one of the most well-known blacks in the United States. He achieved early distinction in football, a sport he discovered at Amherst. He was the first of his race to be named All-American in football, and he received the honor twice. Long after he quit playing, sportswriters would list him as the best roving center in the history of the game.

When President William Howard Taft chose Lewis to be assistant attorney general of the United States, it was the highest federal post ever attained by an African-American. Lewis also became an early advocate for civil rights. His story is quintessentially American, yet he is neglected by scholars today, all but forgotten to history.

Lewis was born during Reconstruction in 1868 in Berkley, Va., a village of African-Americans and whites wedged between Portsmouth and Norfolk. Both of his parents had been slaves, the offspring of white, slave-owning fathers and African-American slave mothers. His father, Ashley Henry Lewis, had been a manumitted slave from North Carolina when he joined the Union Army during the Civil War. Not long after mustering out in Norfolk, he met and married a woman named Josephine Baker. When William was born, Ashley worked as a laborer along the docks of Berkley, later moving the family to Portsmouth, where he became a Baptist minister.

At the age of 15, William was accepted to Virginia’s first college for African-Americans, the Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute, which brought him under the aegis of the institution’s president, John Mercer Langston. Through the efforts of Langston, an African-American abolitionist and lawyer, Lewis was accepted to Amherst in the fall of 1888.

African-American students were few in northern colleges, but the Amherst Class of 1892 had three. Besides Lewis, one was a classmate at Virginia Normal, William Tecumseh Sherman Jackson. The other was George Washington Forbes, a Mississippi native. (See A Slice of History.)

At Virginia Normal, exercise had been limited to the occasional march around the front of the main building. Amherst, however, placed as great an emphasis on development of the body as it did on development of the mind. The college required Lewis to participate in athletics even though he reportedly had never played an organized sport in his life.

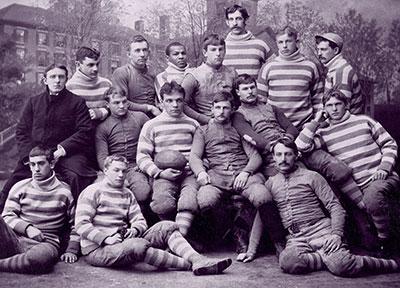

Amherst’s football team in 1891. Holding the ball is William Henry Lewis, Class of 1892. At the time, he and classmate William Tecumseh Sherman Jackson (top row, third from left) were the only African-Americans to play football at a predominantly white college. |

Football was almost exclusively white. In the United States, no other football team at a predominantly white college had African-American players. In Lewis’s sophomore year, Amherst trainer Robert Winston broke the racial barrier by insisting that Sherman Jackson join the varsity team as halfback. By the time Lewis joined at roving center, Jackson had become the star player. The New York Times, in its coverage of an October 1889 game against Yale, singled out Jackson’s performance. The Yale players also singled out Jackson, repeatedly slugging him when he carried the ball. Amherst lost, 42-0, but that was to be expected. Schools like Yale played smaller colleges as tune-ups. For Amherst, success against the bigger opponent had to do with the degree of the loss.

In Lewis’s junior year, Amherst caught Harvard’s defense by surprise and scored a touchdown in the first few minutes of the game. Embarrassed, the Crimson racked up 74 unanswered points, but the damage had been done. Later that year, Amherst stunned Yale by holding the Elis to only 10 points.

His teammates elected Lewis captain for his senior year at Amherst, making him the first African-American to lead a predominantly white football squad. In the 1890s, the captain called the plays and directed the battle on the field. Coaches were not permitted to interfere once play began. Under Lewis’s leadership, the Amherst squad ended the season tied with Williams. The two teams agreed to play one final game for the right to be called league champion.

The 1891 football squad was considered the best in Amherst history, yet the team entered the championship game as the underdog. The players met Williams on Pratt Field, where a series of frosts had turned the ground into a sloppy mess. The game ended in a scoreless tie. Even so, according to football historian William Edwards, Lewis displayed “one of the greatest exhibitions of grit ever seen in a football game.” Lewis “was all over the field on the defense,” Edwards wrote. “When the game was over he was carried off, but refused to leave the field until the final whistle.”

Lewis’s race did not appear to affect his popularity or standing among his classmates at Amherst; they elected him to the Student Senate in his junior year. When Lewis and two others from Amherst attended an annual football convention in 1891, Lewis won election as vice president of the organization. Senior year, his classmates elected Lewis to give the class oration. Lewis’s speech focused on what he termed “the Amherst Idea,” in which men, regardless of background, were equal in the body politic. “The Amherst Idea,” he said, “of liberty, fraternity and equality in the state, of purity, honesty and honor in politics, carried into life, is a panacea for every national ill.”

When the Springfield Republican pronounced on its editorial page that there was no “color line” at Amherst, the Amherst Record retorted that not only was there no color line, it also wasn’t news: “The fact that the college this year graduated three students who had Negro blood in their veins, that they took part in all the class exercises including the senior promenade, and that they were accompanied by young ladies of their own race hardly calls for the extended comment that it has received from the press,” the Amherst paper wrote. “Such comment may, however, be useful in letting the world at large know that the color of a man’s skin has no bearing whatever on the part he may take in the student or social life at Amherst College.”

Lewis, no doubt, could not have agreed more. “Here is no snobbery, no caste, no invidious social distinctions,” he said in his oration. “Every man is a fellow, a member of the true college fraternity.”

Several African-Americans traveled from Boston to attend the graduation. One was W. E. B. Du Bois, a Harvard doctoral candidate who would become the nation’s most prominent African-American scholar. Joining Du Bois was Elizabeth Baker, a young woman from Cambridge, Mass. Du Bois was suitably impressed with Lewis, but Baker was smitten. Baker and Lewis began a courtship, which undoubtedly influenced Lewis’s decision to go to law school at Harvard, only a few blocks from her home. The two married the year after his law school graduation.

At Harvard, eligibility rules of the day allowed Lewis to play football. The exposure of playing in the Ivy League brought him to the attention of Caspar Whitney, who compiled the annual All-America teams. He chose Lewis for the honor in 1892 and 1893. In his final game at Harvard, Lewis’s teammates elected him captain, and he led the Crimson to a stunning victory over a much superior University of Pennsylvania.

Lewis’s 1896 book on college football was one of the first about the sport. |

In 1898, Lewis taught the Amherst team how to play like the powerhouse Penn, which used a unique “guard’s back” formation. As a result, Amherst became, in a way, the Harvard practice squad. Playing against Amherst that year, Harvard adjusted its defense to counter the “guard’s back” strategy. Later, when Harvard played Penn, the practice against Amherst paid off. Harvard went undefeated that year for first time in more than a decade.

Among those who followed Lewis’s Harvard football career with great interest was a young politician named Theodore Roosevelt. Over time, the two men became friends. When Roosevelt was vice president, Lewis visited him in Albany, N.Y. Later, Lewis spent time at the new president’s Oyster Bay residence on Long Island, N.Y. Soon, thanks to Roosevelt, Lewis would again make history, this time off the field.

In 1899 Lewis won election to the Cambridge Common Council from a district that was primarily white. In 1901, Cambridge sent him to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, where he served one year before losing reelection. Then President Roosevelt appointed Lewis as an assistant U.S. attorney for Boston, another first for an African-American.

One of Lewis’s early cases as assistant U.S. attorney concerned a minor instance of political corruption in which two up-and-coming Irish politicians from Boston’s Ward 17 had taken the postal service test for two of their constituents. Lewis knew one of the men—James Michael Curley—having served with him in the state legislature. Lewis handled much of the legwork for the case. At Curley’s trial, the jury deliberated for only 90 minutes before returning a guilty verdict. The conviction added to Curley’s notoriety but had little impact on his future political career; while serving his sentence in the Charles Street Jail he was elected to the Boston Common Council. He went on to be mayor of Boston and, eventually, governor of the state. It seems that Curley held no permanent grudge: he was an honorary pallbearer at Lewis’s funeral.

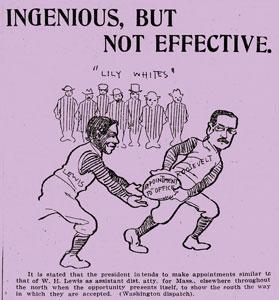

A newspaper offers comment on President Theodore Roosevelt’s appointment of Lewis as an assistant U.S. attorney for Boston. |

Within days after Lewis’s appointment, a notice arrived from the American Bar Association, which had recently made Lewis a member. Because the assistant attorney general had not told the ABA nominating committee his race—probably because no one had asked—the association asked him to resign. Lewis refused. U.S. Attorney General George Wickersham threatened to resign from the ABA if Lewis was expelled. In August, the association voted to retain Lewis and two other African-American lawyers, but with the caveat that all future applicants for membership must state their race.

In 1913, Woodrow Wilson became the first Southern president since Reconstruction. One of his first acts was to segregate federal employees based on race. Within days of Wilson’s inauguration, he also fired William Henry Lewis. Jim Crow, the systematic denial of rights to African-Americans, was migrating north, working its way into the fabric of the entire country. More than 20 years earlier, in fact, Lewis had learned that even Amherst, despite its commitment to equality, was susceptible to the sway of the South.

Lewis’s class at Amherst included two white students from the South. Seymour Herbert Ransom and John Hiram Grant hailed from North Carolina, and between the two of them can be found the story of Reconstruction. Ransom was the son of a distinguished Confederate general and nephew of a U.S. senator. The Ransom family before the Civil War owned a plantation and slaves. Grant, on the other hand, was the son of a carpetbagger who had migrated south from Connecticut after the Civil War and had won appointment to a series of federal posts.

Ransom and Grant were, in their own ways, indicative of a trend that was sweeping the country. The South, formerly perceived as the aggressor in the Civil War, was now finding acceptance as the victim, even in the North.

In the October 1890 edition of the Amherst Literary Monthly, John Kollock, Class of 1892 and son of a Union soldier, wrote a sketch that perpetuated many of the stereotypes about slavery from the “Lost Cause” point of view. The Lost Cause perspective, popular after the Civil War, romanticized the Antebellum South and held that secession from the North had been morally correct because the war was over states’ rights rather than slavery. In Kollack’s sketch, a slave boy sacrifices his life to mail a letter for his master.

Grant won the Lester Prize for his essay, “A Southern View of Reconstruction.” The essay asks Northerners to feel what the South must have felt: “Suppose that you and your ancestors had sustained the same relations as had the Southerner toward the Negro; and he had suddenly in his ignorance and inexperience been given control of your legislatures to make your laws. Imagine such legislation enforced by military rule.”

In December 1890, a student-run lecture series brought the Rev. Thomas Dixon Jr. to Amherst to speak on the topic of “The Negro in the American South.” Dixon, originally from South Carolina, had become one of the most popular preachers in the country. His nondenominational congregation numbered in the thousands in New York City, and he gave speeches around the country to packed houses. More than any other American he codified the Lost Cause into the American psyche.

The 40th reunion of the Class of 1892. Lewis is in the back row, far right. |

Dixon turned his novels into a play, and D. W. Griffith made Dixon’s play and novels into a film, The Birth of a Nation. Released in 1915, the movie glorified the Ku Klux Klan and revolutionized the film industry; it became one of the most popular movies ever made.

When the producers of the movie announced it would open in Boston, a group of African-American leaders, including Lewis, took action. Their strategy was to give the Boston mayor the power to ban entertainment that incited race hatred. Lewis led an effort to lobby for a censorship bill.

The bill met fierce opposition. At one point it nearly died in the Massachusetts Senate, but one of Lewis’s classmates from Amherst, Calvin Coolidge, then president of the state senate, saved the bill at the 11th hour.

As luck would have it, Boston’s mayor had a reputation for banning anything that struck him as the least bit offensive. The Birth of a Nation seemed a perfect place for him to exercise his newfound power. Unfortunately, the mayor was James Michael Curley, and when the vote was cast, Curley sided with the movie producers. The movie played in Boston for six months. Curley’s biographer, Jack Beatty, assumed the mayor had a financial stake in the movie. But just as likely it was payback for William Lewis putting him in jail.

By 1924, the Ku Klux Klan had witnessed a rebirth, thanks in part to the success of The Birth of a Nation. Now a political power to be reckoned with, the Klan exerted its control at the Republican National Convention and over Republican politics. That year, Coolidge was the Republican presidential candidate. Despite Lewis’s repeated appeals, Coolidge lived up to his nickname, “Silent Cal,” and declined to publicly denounce the Klan.

Lewis made what must have been the hardest political decision of his life. “If I consulted my own selfish interests, if I thought of today only, and not of tomorrow, and those who are to come after me, I could probably get more out of the Republican organization than any colored man in America,” he said. Lewis had been a loyal Republican for his entire life, but he endorsed for president the only candidate who had stood up to the Klan, Democrat John Davis.

Lewis issued a scathing attack on the Republican Party that ran some 15 pages. “I am opposing the Republican administration not only because of broken promises, and political cowardice; I am opposing it because of a reversal of its whole attitude toward people of color.” Lewis wrote that he would take his chances with Davis. Lewis’s words were spread across the country, including on the front page of The New York Times.

|

Coolidge easily won election in 1924, and it is doubtful Lewis’s stand had any measurable impact. At the time, most African-Americans in the United States were disenfranchised from the voting process. However, Lewis was at the front of a trend that converted the majority of African-Americans, who had voted Republican since Emancipation, to the Democratic Party. By 1936, the majority had switched, and today, an overwhelming margin of African-Americans vote Democratic. Deval Patrick, the new governor of Massachusetts, won on the Democratic ticket.

Lewis practiced law for the rest of his life. In 1930, he became the first African-American to argue a case before the U.S. Supreme Court alone and win. In the early 1940s he appeared before the Massachusetts Senate to defend Daniel Coakley, a member of the Governor’s Council who became the first Massachusetts public official to be impeached in almost a century. Lewis appeared again before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1944, defending a man who had been convicted of violating the Emergency Price Control Act during World War II. Lewis lost the case; the decision was written by Chief Justice Harlan Stone, Class of 1894, whom Lewis had coached at Amherst some 50 years earlier.

In the final month of his life, Lewis again made headlines, this time for defending a real estate broker charged with bribing several members of the city council in Revere, Mass. The Revere Bribery Case, as it came to be known, was splashed across the front pages of Boston newspapers every day in the late fall of 1948. The case had such a high profile that the attorney general of the Commonwealth, Clarence Barnes, prosecuted the trial personally. One of the men who received the bribe, a Revere city councilor named Leonard Ginsburg, had turned state’s witness. It looked like an open-and-shut case.

Those alive today who attended the trial remember the same thing—Lewis’s brilliant closing argument. “The whole of this case is Ginsburg—Leonard Ginsburg—and nothing else,” Lewis told the jury, speaking slowly and deliberately, according to the Boston Post. “When I saw Leonard Ginsburg on that witness stand, I wondered where I had seen that face before. Then I remembered. I remember a famous painting by Leonardo—a man standing with his hand out—Judas!”

The newspapers called Lewis’s performance dramatic and impressive. Lewis’s remarks also impressed the jury: the 12 men acquitted Lewis’s client and all his co-defendants.

A few weeks later, on New Year’s Eve, Lewis was preparing a motion to appeal the rape conviction of three Pittsfield, Mass., men before the U.S. Supreme Court. The men had been convicted of kidnapping and brutally raping a 15-year-old girl. They were arrested, tried and convicted in less than three weeks and sentenced to the longest term in the region’s history. They never had a lawyer. Lewis had taken their case in 1947 and had managed to reduce their sentence. He was working on the latest appeal when he suffered a fatal heart attack in his Back Bay apartment, sitting in a chair, looking out over Commonwealth Avenue. He was 80.

See also: A Slice of History »

Evan “Josh” Albright is a writer on Cape Cod. He discovered William Henry Lewis 15 years ago while researching his first book, Cape Cod Confidential.

Images: Amherst College Archives & Special Collections