Archives & Special Collections Noah Webster 250th

Skip to Main Content

An Exhibit Commemorating the 250th Anniversary

of

Noah Webster’s Birth

October 16, 1758

Amherst College Library

Archives and Special Collections Department

September 4, 2008 through January 4, 2009

Click here to view the Transcript of the Manuscript History of Amherst College, prepared by Noah Webster

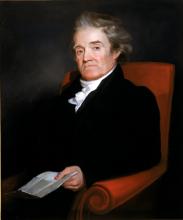

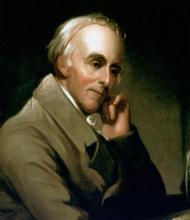

| Portrait of Noah Webster Morse, Samuel Finley Breese American (1791-1872) Noah Webster (1758-1843), 1823 oil on canvas canvas: 30 x 25 in.; 76.2 x 63.5 cm. Bequest of Waldo Hutchins, Jr. Loaned, courtesy of the Amherst College Mead Art Museum and the President’s Office |

In his biography of Noah Webster, Harlow Unger writes,

“In 1823, Yale honored its son by conferring an honorary doctor of laws degree on the great lexicographer. A few weeks later, as a sixty-fifth birthday gift to her father, his daughter Harriet commissioned a more recent Yale graduate, the celebrated portrait artist Samuel F. B. Morse, to paint Webster’s portrait. Morse was the son of Webster’s old friend Jedidiah Morse, author of the great American Geography, for which Webster had written a brief history of America.”

| Bust of Noah Webster Ives, Chauncey BradleyAmerican (1812-1894)Bust of Noah WebsterBronzeOverall: 26 ½ in; 67.31 cmGift of Theodore Bailey, Jr. in memory of Richmond Mayo-Smith (Class of 1909) Loaned, courtesy of the Amherst CollegeMead Art Museum |

Noah Webster was born on his father’s farm in West Hartford, CT. on October 16, 1758. Because of his love of study and books, his father decided to mortgage his house to send him to Yale. His education at Yale was temporarily interrupted when he and his brothers, as volunteer militiamen, marched under his father’s command to help prevent Burgoyne from linking forces with Clinton along the Hudson River.

Having graduated from Yale in 1778, Noah Webster studied law part-time and became a schoolmaster in Hartford, CT to support himself. As a schoolmaster, he encountered “the absolute impossibility of obtaining books,” overcrowded classrooms with 70 to 80 students of all ages, poor facilities, and inadequate heating. Webster decided to address these problems by opening his own school in 1781 and by developing a new system of education that would emphasize history, geography, political science, and arithmetic.

Webster came to the conclusion that speech was as essential to education as spelling, reading, and writing. Realizing that the variety of languages and dialects that were being spoken by the American people could lead to disunity, he decided to promote a new, common language for America. He thought that the pronunciation of words taught in the schools was “wretched,” and he hoped to alleviate this problem by eliminating “those distinctions of provincial dialects which are objects of reciprocal ridicule in the United States.” To remedy this problem, he decided to write a book of instruction for children in three parts: spelling, grammar, and readings from the works of American patriots. These were to be the first truly American textbooks for children.

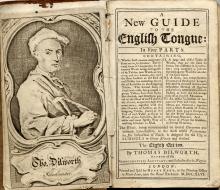

| The Dilworth Speller A New Guide to the English Tongue, in Five Parts by Thomas Dilworth. 8th edition. London, Printed and Sold by Henry Kent… 1746.

|

The Dilworth Speller was first published in 1740 by an English cleric and author of schoolbooks. This may be the earliest known perfect copy of the most important speller used in American schools prior to the publication of Webster’s speller. Dilworth directed children to pronounce every letter of words such as “sub-tle” and “o-ce-an.” He insisted that suffixes such as –cion, -sion, and –tion be pronounced as two syllables. The examples in his book advocated loyalty to the king and to England and listed only English towns and shires. It was a book written for English children. Webster remarked that “One half of the work is totally useless.” Yet, it was used in most American schools for lack of anything better.

The Grammatical Institute of the English Language

| Part I: The Speller A Grammatical Institute, of the English Language, Comprising, an Early, Concise, and Systematic Method of Education, Designed for the Use of English Schools in America. In Three Parts. Part I. Containing, a new and accurate Standard of Punctuation. By Noah Webster, A.M. Hartford: Printed by Hudson & Goodwin, for the author. [1783] A facsimile Edition by Connecticut Printers Incorporated for the Noah Webster House Foundation of which one hundred numbered deluxe copies have been bound with paper sides and leather backbone and reserved for the benefactors of the Foundation in 1968. This is No. 8 of 100 deluxe copies. |

The Speller

The Webster Speller was the first part of Webster’s three-part Grammatical Institute. All its words were commonly used and of practical value. He provided definitions, a guide to pronunciation, instructions on accent, tables of progressively more difficult words, and short tales for practice in pronunciation. He also included a section on the geography of the American states and “A Chronological Account of Remarkable Events in America.” Henry Steele Commager wrote, [Webster’s Blue-Backed Speller] caught on, at once; within a few years it all but monopolized the field; under its benign guidance generations of young Americans learned the same words, the same spellings, the same pronunciations; read the same stories; absorbed the same moral lessons. It was part of a larger program – a program for cultural as well as political independence from the Mother Country… The Speller, and after it the Grammar, the Reader, and the Dictionaries assured Webster a place among the Founding Fathers.”

| Part II: The Grammar A Grammatical Institute, of the English Language… Part II. Containing, a plain and comprehensive grammar…. By Noah Webster. The Fourth Edition, with many corrections and improvements, by the author. Boston, Printed by Isaiah Thomas and Ebenezer T. Andrews. 1796.

|

The Grammar

The second part of Webster’s Grammatical Institute was first published on March 2, 1784. Webster’s grammar was ground-breaking in that it did not base its rules for the English language on the rules of Latin. His American grammar eliminated the declensions of nouns (i.e. the nominative, objective, dative, and ablative cases.) Nouns preceding a verb were subjects; nouns following a verb or preposition were objects. He called a few verbs, such as to be, “auxiliary” verbs; the rest he categorized as transitive, intransitive, or passive. He eliminated the subjunctive mode.

Part III: The Reader

| Part III: The Reader An American Selection of lessons in Reading and Speaking: calculated to improve the minds and refine the taste of youth: and also to instruct them in geography, history and politics of the United States… Third edition, with many corrections and improvements by the author. Boston, Printed by Isaiah Thomas and Ebenezer T. Andrews, 1793, c1791.

|

The Reader

Webster finished the third part of his Grammatical Institute in 1784 and published it in February, 1785. In his preface he commented that there were many compilations of readings for colleges and academics, but that there were no readers for the American schools. He considered it a “capital fault” that the readers used in American schools “contain subjects wholly uninteresting to our youth; while the writings that marked the revolution, which are perhaps not inferior to the orations of Cicero and Demosthenes… lie neglected and forgotten.” This book was the first literary anthology for the children of the United States.

Copyright

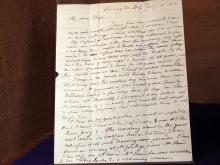

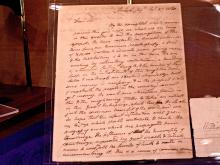

| Letter from Noah Webster to Eliza W. Jones, January 10, 1831. [2] p. Amherst College Library. |

Copyright

One of Webster’s chief worries about his Grammatical Institute was that it would be pirated by unscrupulous publishers. James Madison and Thomas Jefferson pointed out that the Articles of Confederation did not authorize Congress to enact copyright laws. Consequently, Webster had to seek copyright protection from each state. Finally, on May 31, 1790, President Washington signed the United States’ first general copyright act into law. Later, Webster lobbied for an extended copyright law. In this letter to Eliza W. Jones, he wrote that his “business in part was to use my influence to procure an extension of the law for securing copy-rights to authors.” He added that, “By this bill the term of copy-right is secured for 28 years, with the right of renewal … for 14 years more. If this should become law, I shall be much benefited.” The new federal copyright law was passed and remained in effect until 1909.

Other Publications

| Sketches of American Policy … By Noah Webster. Hartford, Printed by Hudson and Goodwin, 1785. Facsimile edition, edited with introduction and bibliographical note by Harry R. Warfel. New York, Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints, 1937. |

The first three of Webster’s Sketches are based on Rousseau’s Contrat Social. The fourth and most important sketch presents an argument for reorganization of the national government that may have influenced Washington, Madison, and others who prepared the Constitution after reading Webster’s book. Madison, however, refused to acknowledge special significance to his reading of Webster’s Sketches. Harry R. Warfel suggests that “Webster was not the inventor but the penman, the annalist, the journalist, setting down opinions more or less commonly held.”

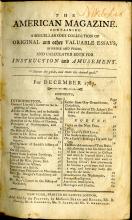

Benjamin Franklin suggested that Webster found his own magazine similar to ones that already were being published in Boston, New Haven and Philadelphia. Webster chose to found it in New York City because it lacked a magazine of commentary and literature. He wrote in the magazine’s introduction that he was “determined to collect as many original essays as possible; and particularly such as relate to this country…” In essays Webster wrote for the magazine, he called for universal public education, female education, and the abolition of slavery. The American Magazine was published for just one year.

| The Effects of Slavery on Morals and Industry. By Noah Webster. Hartford, Printed by Hudson and Goodwin, 1793.

|

Webster was an early and ardent abolitionist. He supported Benjamin Rush when Rush was attacked for urging a constitutional amendment to emancipate the slaves. Having seen slavery in the South on his travels, he was instrumental in the founding of the Connecticut Society for the Abolition of Slavery and gave the principal speech at its first annual meeting in May 1793. This essay was published later that year as a pamphlet.

| The Prompter; or a commentary on common sayings and subjects, which are full of common sense, the best sense in the world. Boston, Printed by I. Thomas and E. T. Andrews, 1793. |

The Prompter was a compilation of 28 popular essays published originally in the Connecticut Courant. Because of its wide appeal, it was published in more than one hundred editions during a 60-year period.

| A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases, with the principal phenomena of the physical world, which precede and accompany them and observations deduced from the facts stated. In two volumes. By Noah Webster. Hartford: Printed by Hudson & Goodwin, 1799. |

Webster’s biographer, Harlow Unger, states that “Webster’s two-volume work – 712 pages – was the world’s first study of epidemic diseases and became the standard text on the subject in medical schools around the world for much of the nineteenth century… On the cause of the fever, Webster himself concluded that electricity produced “carbonic gas vapors” in the air, which, when inhaled, led to influenza and catarrh, which he said were the precursors of yellow fever.”

| History of the United States; to which is prefixed a brief historical account of our [English] Ancestors, from the dispersion at Babel, to their migration to America and of the conquest of South America by the Spaniards. By Noah Webster. New Haven: Published by Durrie & Peck; Louisville, KY.: Wilcox, Dickerman, & Co., 1832. |

Webster’s History of the United States begins with an account of the creation and continues through the conquest of England and the peopling of America. It includes the history of American settlements, the Indian wars, the Revolutionary War, and the formation of the Constitution of the United States. Its use was wide-spread.

| The Holy Bible, containing the Old and New Testaments, in the Common Version. With amendments of the language, by Noah Webster. New Haven: Published by Durrie & Peck, 1833. |

In his edition of the Bible, Webster substituted new words and phrases for those that were obsolete, corrected errors in grammar, and inserted euphemisms for words and phrases that he considered to be offensive (e.g. lewdness or lewd deeds for fornication.) Unfortunately, the public had no interest in Webster’s Bible, and it became quite rare.

Noah Webster and the Founding of Amherst College

| Old Academy. Amherst, Mass. [Photograph] Lovell Photo. |

In September 1812 Webster moved from New Haven, CT to Amherst, MA. He was upset by the conditions of the school in Amherst. The following year Webster helped raise funds for an academy “where their sons could be fitted for college and their daughters taught the higher branches of education.” As president of the board of trustees, Webster opened the Amherst Academy in 1815 to 90 girls and more than 100 boys. The Rev. Nahum Gould wrote about the Academy as follows: “None need leave on account of pecuniary embarrassments. Tuition was free to any pious student who was preparing for the gospel ministry. Board was one dollar a week, and if this could not be afforded, there were families ready to take students for little services which they might render in their leisure hours.” The great success of the Academy encouraged the trustees to begin a fund-raising effort “for the gratuitous instruction of indigent young men of promising talents and hopeful piety, who shall manifest a desire to obtain a liberal education with a sole view to Christian ministry.” This was the basis for the founding of Amherst College.

| Printed Letter from Noah Webster, John Fiske, and Rufus Graves, by order of the Board of Trustees, Amherst, Sept. 11, 1818, to the settled ministers of the gospel, within the three counties of Hampshire, Hampden and Franklin, and of the towns in the western part of the county of Worcester.

|

This letter invites the ministers of the area, attended by lay-delegates, to “meet in convention with the subscribers to the [Amherst College] fund, at the church in the West Parish in Amherst” on Tuesday, September 29, 1818, at nine A. M. to deliberate on the need to establish a charitable institution in Amherst.

| Letter from Noah Webster, Amherst, MA, to William Leffingwell, New Haven, CT,. Sept. 27, 1820. Amherst College Library. |

Webster’s letter to William Leffingwell reports “we have collected in small subscriptions from our common people chiefly, a sum of $50,000 dollars [equivalent to $1,000,000 today] to educate pious young men.” He writes further “…we do hope that this infant institution will grow up to a size which shall contribute to check the progress of errors which are propagated from Cambridge. The influence of the University of Cambridge [Harvard], supported by great wealth and talents, seems to call on all the friends of truth to write in circumscribing it. This is a cause of common concern.”

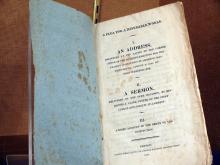

| A Plea for a Miserable World. I. An Address Delivered at the Laying of the Corner Stone of the Building Erecting for the Charity Institution in Amherst, Massachusetts, August 9, 1820, by Noah Webster, esq. II. A Sermon, Delivered on the Same Occasion, by Rev. Daniel A. Clark… III. A Brief Account of the Origin of the institution. Boston: Printed by Ezra Lincoln, 1820. |

Webster gave the principal address at the corner stone laying ceremony for the first Amherst College building, South Dormitory. In his address he stated, “Let us then take courage! The design is unquestionably good, and its success must be certain. Small efforts combined and continued, cannot fail to produce the desired effect, and realize the hopes of its founders. Prudence and integrity will subdue opposition, and invite co-operation; perseverance will bring to our aid new accessions of strength, and a thousand small streams of charity from unexpected sources, will flow into the common current of benevolence…” At the end of the exercises, Webster was elected as the second president of the Amherst College Board of Trustees.

| A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language. By Noah Webster. From Sidney’s Press. For Hudson & Goodwin, Hartford, and Increase Cooke & Co., book-sellers, New Haven, 1806. |

In 1804, Webster began work on a small dictionary based on an English dictionary written by John Entick. Webster’s Compendious Dictionary, which he considered to be a supplement to his previously published speller, contained more than 40,000 words, including approximately 5,000 new words that he gleaned from writings by American authors. It also eliminated English words no longer used by Americans. To his critics’ surprise, Webster proposed spelling changes for just a few words. Some caught on; others were ignored.

| A Dictionary of the English Language; compiled for the use of common schools in the United States. By Noah Webster. From Sidney’s Press, N. Haven. Printed for John and David West, Boston…, 1807. |

This abridged version of the Compendious Dictionary contained about 30,000 words. It sold for just $1.00. Webster tested his pronunciation rules by checking to see if his children could understand them.

| An American Dictionary of the English Language… in two volumes. By Noah Webster. New York: Published by S. Converse. Printed by Hezekiah Howe – New Haven, 1828. |

Webster’s biographer, Harlow Unger, reports that in preparation for his great American Dictionary, Webster “restudied his college Greek, Latin, and Hebrew; perfected his French and German; and then studied Danish, Anglo-Saxon, Welsh, Old Irish, Persian, and seven Asiatic and Assyrian-based languages.” He began his work on the great dictionary in New Haven in 1808 and continued it in Amherst from 1812-1822. After consulting most of the available American library resources, Webster traveled to France and England to complete his research by consulting early etymology dictionaries at Paris, Cambridge and Oxford. In January 1825, Webster wrote, “When I had come to the last word, I was seized with a trembling which made it somewhat difficult to hold my pen steady for writing. The cause seems to have been the thought that I might not then live to finish the work, or the thought that I was so near the end of my labors. But I summoned strength to finish the last word, and then walking about the room a few minutes I recovered.” The American Dictionary contained 70,000 words and sold for $20. Congress, state legislatures, and the courts adopted it as their official standard. With its publication, Webster became known as the father of the American language.

| A Dictionary for Primary Schools. By Noah Webster. New York: Published by N. & J. White, …Stereotyped at E. White’s. New Haven: Durrie & Peck, 1833. |

Webster published this school dictionary to accompany his speller. It used the spelling he had established in his American Dictionary of 1828. A copy in the Huntington Library belonged to Abraham Lincoln.

| An American Dictionary of the English Language; first edition in octavo… in two volumes. By Noah Webster. Amherst, Mass. Published by J. S. and C. Adams…, 1844. |

Newton F. McKeon and Katharine C. Cowles report that this edition was made up from unsold sheets of the 1841 edition. The publisher most likely printed only the title pages for the copies that were bound. McKeon contends that “this modest job was the only contribution which Amherst presses made to the bibliography of Webster’s Dictionary.”

| McGuffey’s Newly Revised Eclectic Second Reader: containing progressive lessons in reading and Spelling. Revised and improved. By Wm. H. McGuffey. Permanent stereotype edition. New York: Clark, Austin, and Smith, Cincinnati: W. B. Smith and Co. [1848] |

The popular McGuffey Readers, while replacing Webster’s Reader, assured the continuing success of his Spellers by using only Webster’s orthography. Children had to learn to read, write, and spell with Webster’s speller before they moved on to McGuffey Readers.

| An American Dictionary of the English Language… By Noah Webster. Revised and enlarged by Chauncey A. Goodrich. Springfield, Mass.: Published by George and Charles Merriam, 1854. |

George and Charles Merriam bought the exclusive rights to publish Webster’s dictionary and hired Webster’s son-in-law, Chauncey Goodrich, to edit an enlarged and improved edition. This edition first appeared in 1847. The G. and C. Merriam Company presented this copy of this edition to the Amherst College Library in 1854.

| An American Dictionary of the English Language. By Noah Webster. Thoroughly revised, and greatly enlarged and improved. By Chauncey A. Goodrich… and Noah Porter… 2 vols. Cambridge: Printed at the Riverside Press for G. & C. Merriam, Publishers, Springfield, Mass., 1865. |

In 1859, the G. & C. Merriam Company hired the German philologist, C. A. F. Mahn to rewrite and convert Webster’s dictionary into an edition that contained more than 140,000 words as well as hundreds of illustrations to accompany the word definitions. In 1864, the Merriam Brothers appointed Noah Porter, who was later to become the President of Yale, to serve as editor in chief of this new, two-volume, unabridged edition of the dictionary. After his retirement from Yale in 1871, Porter returned to the Merriam Company to edit the Webster’s International Dictionary of the English Language, of 1890.

| Lock of Noah Webster's hair. In Noah Webster’s time, it was not unusual to preserve a loved one’s lock of hair. When Rebecca Greenleaf initially refused Webster’s proposal of marriage and was about to return to her home in Boston, in June, 1787, Webster wrote to her, “Without you the world is all alike to me; and with you any part will be agreeable. As a pledge of my sincerity, accept a lock of hair, and keep it no longer than I deserve to be remembered. You must go, and I must be separated from all that is dear to me; but you will be attended by guardian angels and the best wishes of your sincere and respectful admirer.”

|

In Noah Webster’s time, it was not unusual to preserve a loved one’s lock of hair. When Rebecca Greenleaf initially refused Webster’s proposal of marriage and was about to return to her home in Boston, in June, 1787, Webster wrote to her, “Without you the world is all alike to me; and with you any part will be agreeable. As a pledge of my sincerity, accept a lock of hair, and keep it no longer than I deserve to be remembered. You must go, and I must be separated from all that is dear to me; but you will be attended by guardian angels and the best wishes of your sincere and respectful admirer.”

| Silhouette of Rebecca Greenleaf Webster. |

Rebecca Webster’s granddaughter, Emily Ellsworth Fowler Ford, provides the following description of her grandmother, Rebecca Greenleaf, shortly after her marriage to Noah Webster. “At this time she was very pretty, with bright, dark eyes and hair, and straight small features. She was little of stature, and of light weight, but was very erect and graceful.”

Circle of Noah Webster's Friends and Associates

|

George Washington – Washington asked Webster to come to Mount Vernon as a tutor for his grandchildren. Webster replied that “books & business will ever be my principal pleasure. I must write – it is a happiness I cannot sacrifice.”

|

| James Madison – Madison read and admired Webster’s Sketches of American Policy. The ideas Webster set forth in his Sketches are thought to have had some influence on the writing of the Constitution of the United States. |

| Benjamin Franklin – Webster and Franklin were both interested in spelling reform. In 1786, Franklin wrote to Webster, “Our Ideas are so nearly similar, that I make no doubt of our easily agreeing on the Plan, and you may depend on the best Support I may be able to give it as Part of your Institute. |

| Alexander Hamilton – In 1793. Hamilton, John Jay, and others funded the establishment of a pro-government, anti-Citizen Genet, newspaper in New York City that would rally support for the president. They selected Noah Webster as the editor for the paper, the American Minerva. |

| John Jay – Jay was the President of the Continental Congress, Ambassador to Spain and France, a co-author of the Federalist Papers, Jay was one of the principal subscribers to Webster’s and the first Supreme Court Chief Justice.American Dictionary. |

Courtesy of the Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States (Artist Casimer Stapko after Gilbert Stuart)

| Benjamin Rush – Rush was a prominent Pennsylvania physician, writer, and educator who signed the Declaration of Independence and attended the Continental Congress. Rush helped Webster by providing information on yellow fever for Webster’s Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases. |

| Samuel Adams – Adams was an influential political writer who helped gather support for rebellion against the British. In 1784 he supported Webster’s stand against the Middletown Convention which sought to undermine the authority of Congress. |

| Marquis de Lafayette – Lafayette was the French hero of the American Revolutionary War. When he visited Hartford on his triumphal tour of the United States in 1784, Webster was among the people who dined with him. |

| Daniel Webster – Daniel Webster was Noah Webster’s cousin. Daniel Webster was best known as a Senator, but also as Secretary of State and as a Representative from Massachusetts’ 1st district. He sponsored Noah Webster’s proposed copyright bill in the Senate in 1831. |

| Isaiah Thomas – Thomas, publisher of The Massachusetts Spy (1770-1802), was considered the official patriot printer. He served as one of Webster’s printers and booksellers. |

Books Given by Noah Webster to the

Amherst College Library

Adair, James, ca. 1709-1783. The history of the American Indians; particularly those nations adjoining to the Missisippi [!] East and West Florida, Georgia, South and North Carolina, and Virginia… London: E. and C. Dilly, 1775.

Appianus, of Alexandria. Historia Romana, Latin and Greek. [Genevae]: Excudebat Henricus Stephanus, Anno M. D. XCII [1592]

Barton, Benjamin Smith, 1766-1815. Elements of botany, or, Outlines of the natural history of vegetables: illustrated by thirty plates. Philadelphia: Printed for the author, 1803.

Berkeley, George, 1685-1753. Alciphron, or The minute philosopher. 4th ed. New Haven, From Sidney’s Press, for Increase Cooke & Co., 1803

Clarke, Francis L. and William Dunlap, 1766-1839. The life of the most noble Arthur, Marquis and Earl of Wellington…New York: Printed and published by Van Winkle and Wiley, 1814.

Connecticut. Acts and laws of the State of Connecticut, in America. Hartford: Printed by Hudson & Goodwin, 1805.

Derham, William1657-1735. Physico-theology: or, A demonstration of the being and attributes of God, from His works of creation… A new edition; with additional notes. London: A. Strahan, 1798.

Douglass, William, ca. 1700-1752. A summary, historical and political, of the first planting, progressive improvements, and present state of the British settlements in North-America. 2 vols. Boston, New-England, Printed: London, re-printed for: R. Baldwin, 1755.

Everett, Edward, 1794-1865. Orations and speeches on various occasions. 1st ed. Boston: C.C. Little and J. Brown, 1836.

Faber, George Stanley, 1773-1854. A dissertation on the mysteries of the Cabiri: or, The great gods of Phenicia, Samothrace, Egypt, Troas, Greece, Italy, and Crete: being an attempt to deduce the several orgies of Isis, Ceres, Mithras, Bacchus, Rhea, Adonis, and Hecate, from a union of the rites commemorative of the deluge with the adoration of the hosts of heaven. 2 vols. Oxford: At the University press for the author, and sold by F. and C. Rivington, 1803.

Franklin, Benjamin, 1706-1790. Political, miscellaneous, and philosophical pieces… London: Printed for J. Johnson, 1779.

Gillies, John, 1747-1836. The history of ancient Greece… 4th ed. London: Printed by A. Strahan for T. Cadell, Jun., and W. Davies, 1801.

Horsley, Samuel, 1733-1806. Sermons. New York: Printed and sold by T. and J. Swords, 1811.

Junius, Franciscus. 1589-1677. Etymologicum Anglicanum… Oxonii: e theatro Sheldoniano, 1743.

Massillon, Jean-Baptiste, 1663-1742. Sermons. Complete in two volumes. Brooklyn: Printed by T. Kirk, for John Conrad, and Co. Booksellers, Chestnut-Street, Philadelphia, 1803.

Münscher, Wilhelm, 1766-1814. Elements of dogmatic history; translated…by James Murdock. New Haven: A. H. Maltby, 1830.

Pausanias. The description of Greece. Tr. From the Greek, with notes, in which much of the mythology of the Greeks is unfolded from a theory which has been for many ages unknown. 3 vols. London: Printed for R. Faulder, 1794.

Pausanias. Pausaniae Graeciae description accurate… Lipsiae: Apud Thomam Fritsch, 1796.

Pennant, Thomas, 1726-1798. Arctic zoology. 2 vols. in 3. London: R. Faulder, 1792.

Vetus Testamentum Graecum. Londini: Excudebar Rogerus Daniel Prostat autern venale, 1653.

Robertson, William, 1721-1793. An historical discquisition concerning the knowledge which the ancients had of India; and the progress of trade with that country prior to the discovery of the passage to it by the Cape of Good Hope… Philadelphia: Printed by William Young, bookseller, 1792.

Skinner, Stephen, 1623-1667. Etymologicon linguae anglicanae… Londoni: typis T. Roycroft, & prostant venales apud H. Brome, 1671.

Smith, William, 1728-1793. The history of the province of New-York, from the first discovery to the year M.DCC.XXXII… London, Printed for Thomas Wilcox, 1757.

Stone, William L. (William Leete), 1792-1844. Letters on masonry and anti-masonry, addressed to the Hon. John Quincy Adams. New York: O. Halsted, 1832.

This exhibit was prepared by Willis Bridegam, Librarian of the College, emeritus, with the assistance of Marian Walker, Mariah Sakrejda-Leavitt, Margaret Dakin, Susan Sheridan, and Stephen Fisher. The Library is grateful to President Anthony Marx and Elizabeth Barker, Director and Chief Curator of the Mead Art Museum, for the loan of the Samuel Morse portrait of Noah Webster and the Chauncey Bradley Ives Bust of Noah Webster.

9/17/08