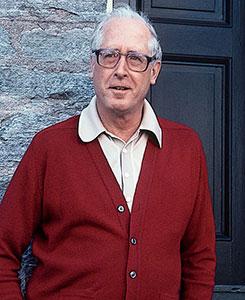

In his teaching and writing, Theodore Greene ’43, professor emeritus of history and American studies, relished the storytelling as much as the story. |

Theodore P. Greene ’43, the history and American studies professor who in a long Amherst career personified many of the traditional-but-progressive, best features of the college, died of cancer Jan. 15. Greene, who lived in Amherst, was 85.

“He embodied the best traditions of Amherst but was always open to change,” N. Gordon Levin, the Dwight Morrow Professor of History and American Studies, recalled in a tribute. “He took great interest in helping to shape change, and guide it, and it’s difficult to imagine some major decisions without Ted having a role.”

Greene was proud, especially, of his role in the 1974 decision to make Amherst coeducational. He is also remembered as an outstanding teacher, lecturer and historian. Frederic L. Cheyette, professor emeritus of history, describes Greene as a “stout-hearted defender of the real values of the college.”

Born in New York City, Greene spent his early years in New Britain, Conn., and attended Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, graduating first in his class. Although this distinction won him admission to Harvard, he chose instead to enter Amherst, following long family tradition. After graduating from Amherst, he served in the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II in Denver, Colo., where he met his future wife, Mary Jane “Jary” England. Greene pursued graduate studies at Columbia University before returning to Amherst in 1952.

Over the next 37 years, he taught courses in American colonial, social, intellectual, frontier and diplomatic history. He retired in 1989 as the Winthrop H. Smith Professor of History and American Studies, Emeritus.

A reserved New Englander, anything but flashy, Greene set high standards for his own scholarship and the work of students. Between 1955 and 1969 Greene edited three “Problems in American Civilization” paperbacks produced by the college’s pioneering American studies program. These were American Imperialism in 1898, Wilson at Versailles and Roger Williams and the Massachusetts Magistrates. Greene wrote another book, America’s Heroes, and edited two local history books, Essays on Amherst’s History and 250 Years at First Church in Amherst, 1793-1989.

In his teaching and writing, Greene relished the storytelling as much as the story; the stories he most enjoyed telling concerned the history of Amherst, both college and town. Often he noted parallels between the past and present. He observed in the late 1960s, for instance, that disruptions by student radicals were nothing new. “When Baptists [in Amherst] refused to allow an abolitionist to speak in their church,” he said, “some student members of the Anti-Slavery Society attempted to disrupt Baptist services by firing off a cannon. Unfortunately the cannon exploded, and one student lost a hand.” Greene was often called upon to write or lecture for anniversaries and other special occasions. He delighted readers and audiences with his flair for apt quotations and lively anecdotes.

In 1974, Greene chaired one of the committees studying coeducation at Amherst, and wrote a 76-page final report of its findings. The conclusion bore the unmistakable stamp of Greene’s Yankee practicality: “The question is not whether a significant college like Amherst can with justice continue to exclude women,” he wrote. “The question is whether Amherst can remain as significant and vital a college in the future if it does not admit women.” Greene described an earlier transitional period, the 1950s and early 1960s: “As a few more blacks, many more Jews and gradually more Catholics appeared within these walls, as prep-school admissions dropped to 30 percent while public schools rose to 70 percent, the possibilities for a new kind of Amherst community began to emerge.

“But all these new sons of Amherst found themselves simply with a ticket of admission to the old Amherst ethos, to the world of fraternities which now prided themselves for accepting blacks, to a required core curriculum which embodied the best of the liberal White Protestant traditions.”

As Hugh Hawkins, the Anson D. Morse Professor of History and American Studies, Emeritus, remarked at Greene’s funeral service on Feb. 3, “No one was more ready to see when the old ways didn’t fit the new students.” Hawkins also recalled that John William Ward once told the Amherst Student that Greene was the person who had most influenced him in his years as president of the college—“that Ted knew more about where the college came from and where it ought to be heading than anyone else.”

To Greene, the college’s history was almost a family chronicle: he and his brother, Thayer Greene ’50, were third-generation alumni whose father was the Rev. Theodore Ainsworth Greene ’13 and whose grandfathers were both in the Class of 1882. Ten other family members also went to Amherst.

Beyond the campus, Greene served in 1962-63 as president of the New England American Studies Association. He demonstrated for civil rights legislation in the 1960s and against the Vietnam War in the 1970s. He was active in securing integrated, low-income public housing for the town of Amherst. He enjoyed world travel—and trips to Fenway Park to see the Boston Red Sox. And he took care of the family’s ancestral home in Jaffrey, N.H.

Besides his wife and brother, Greene is survived by two daughters, Jennifer Greene and Dorothy LeBlevec; a son, Stephen; four grandchildren; and a great-grandchild.

Photo: Frank Ward