|

College Student A thinks she’s fat, certainly fatter than College Student B, who seems to have the ideal body. Student B must work out all the time and eat nothing but salads and tofu, her admirer believes. But in reality, Student B exercises only a couple times a week, likes to pig out on burgers and fries and weighs 15 pounds more than Student A imagines. The two women never discuss these matters. In an effort to fit in, Student A starts skipping meals and develops an eating disorder. The stick-thin images propagated by the media only spur her on.

For years, Catherine Sanderson, associate professor of psychology, has been studying this phenomenon: college women who develop eating disorders because they misperceive the eating and exercise habits of their peers.

Her latest research on the topic, conducted with Jenny Wallier ’00 and Jan Stockdale of the London School of Economics and Darren Yopyk of UMass Amherst, focused on a younger demographic. An extension of Wallier’s Amherst thesis (and part of her master’s thesis at LSE), the study examined how high school girls in the United States and Great Britain feel about their bodies in relation to the perceptions they hold about their peers’ bodies. It also asked whether these often-faulty perceptions lead to eating disorders. In addition, Sanderson and her team looked at the role that culture plays in the equation: is the Student A/Student B scenario a universal phenomenon among adolescents, or is it endemic to American culture?

For the study, 272 girls (from two private, all-girls secondary schools in the United States and one private, all-girls secondary school in England) answered questions about their drive to be thin, their reasons for exercising and why they think others want to exercise. The study asked them to evaluate both their own bodies and their ideal body sizes, as well as the actual and ideal body sizes of the typical girl at their school.

The findings were on par with Sanderson’s earlier research about college students: both American and British high-school girls perceived their classmates to have smaller, thinner figures than their own; they perceived other girls to want smaller bodies than they wanted for themselves; they believed their peers were more likely to exercise to control their weight; and they saw their own figures as larger than their ideal figures.

The research, published in December in the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, found that such misperceptions not only begin in adolescence but are also culturally universal, at least in Western cultures. (Eventually, Sanderson would like to expand her research beyond the West.) Perhaps most important, the study showed that misperceptions among the young women contribute directly to the development of eating disorders.

What’s the solution? Sanderson and Wallier believe that speaking openly can help. “Saying to students, ‘You know what, you think you’re heavier than your classmates, but you’re not; you think other women want to be very thin, but they don’t; you think other women exercise all the time, but they don’t,’” says Sanderson. “There is tremendous pressure on women to try to meet these false norms, and it also makes them feel alienated from their culture. Simply knowing about [the misperceptions] helps women engage in behavior to try to combat them.”

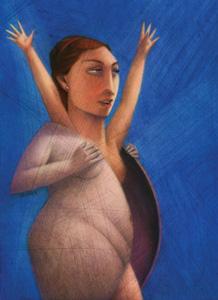

Illustration by Cathy Gendron, courtesy of thespot.com.