Interview by Katherine Duke '05

Ben Lieber has been dean of students at Amherst since 1984 and will move on to a new position at the college in 2010. This year, he brought decades of perspective—and a brand-new beard—to his final First-Year Orientation. He spoke recently about his experiences:

Ben Lieber in 2009 in his office in Converse Hall |

On the history of college orientations

It’s actually a very interesting study in social history, I suspect. The practice back when I was in college, which was in the late ‘60s, and I’m sure well before that, was to have a very truncated orientation—maybe a speech by the president and a speech by the dean, and then you were sort of thrown into things, and it was sink or swim. Particularly as a result of the social and political turmoil of the ‘70s and the early ‘80s, colleges came to be seen as much more complicated, heterogeneous places, where a lot of social and political issues were playing out in ways that hadn’t necessarily been the case in previous generations. And I think colleges felt the need to begin addressing those issues, so orientation programs expanded correspondingly. The fact, for instance, that Amherst began admitting women in the late 1970s raised the need for the college to address gender issues that simply hadn’t been present previously. Same thing with racial issues, issues of sexual orientation. As this world became more diverse and more complicated, so too did orientation programs, and I think it reached the stage where, for virtually any issue that one could think of, the immediate impulse was, “Well, we need to address it somehow in orientation.”

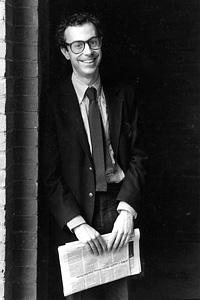

Ben Lieber outside of Fayerweather Hall, 1985 |

On conversations

There were a series of years, particularly those early years when Dean [Onawumi Jean] Moss [associate dean of students from 1985 to 2006] was first here, when a lot of these issues really were pretty fraught. She conducted a session during Orientation every year called “Conversations on Being at Amherst.” At a time when a lot of students found it difficult and awkward to talk about things like race and their own backgrounds and their own conceptions and misconceptions, those were, very, very important and moving conversations. It was a product, I think, of Dean Moss’s skill and sensitivity in running them, but it was also a sign of one of the best things about Amherst College, which is the goodwill that students bring to it. It’s a place where students, whatever their backgrounds, come hoping to engage closely with their fellow students. I think the scale and the size of the college enable that. Compared to four years of living and interacting with each other, and compared to the actual educations that students get, Orientation is trivial. We place a lot of symbolic weight on Orientation that it really can’t carry, because it is such a small portion of a student’s time here. Nonetheless, there are occasional moments that really are striking, such as those “Conversations.”

On students and their parents

The people who are coming to college now are, in many cases, the children of parents who went through these [long, issue-focused] orientations themselves. I think today’s students come to places like Amherst expecting to come to a much more diverse and complicated world, and many of them have grown up thinking about these issues in ways that previous generations maybe didn’t have to before they got to college. So I find this generation of students actually very, very open to these issues. Similarly, I think parents are much less anxious about these issues. It’s a cliché at this point to say that many of them [are] hyper-involved in their sons’ or their daughters’ lives. But they’re less worried about, “Is the college going to be talking too much to my son or daughter about sex?” or “Is my son or daughter going to have problems with a roommate because they’re of a different racial background?” I think there’s an expectation that the world has changed, changed for the better, and that it’s important for students to participate in that. To the extent that students and their parents are coming in more and more anxious, it is about questions of academic success and academic pressure and “How do I choose my future, in academic terms?” The result is that the Orientation Committee has placed an even greater emphasis on academic issues—and especially issues of academic support—than may have been the case a decade or 15 years ago.

On his duties

Orientation really is run by the Orientation Committee, which is chaired by the dean of new students, Allen Hart, Class of ’82 and professor of psychology. Many of my duties basically involve showing up. I do give a speech to the freshman class—kind of a welcome speech—along with several other people, including the director of admissions, the dean of new students, the president, the president of the student government and the dean of the faculty. Then the dean of new students and I do a session involving both academic and social behavior on campus, introducing the students to the rules and regulations and having them sign the Honor Code, which we’ve been doing for the last five years now. Otherwise, a lot of what I do is mingle and meet the freshmen and just start getting to know them.

On making a fool of himself

Both my worst and my best memories involve the multiple ways that upperclass students have figured out to have me humiliate myself during Orientation. That generally involves the RCs [Resident Counselors] and the RC Show, which is a custom that predates my arrival here: it started in the late 1970s. ([Before that], I think there were other means of humiliation, usually by taking the dean of students captive, but those were different times.) A dean named Kathy Deignan, who supervised the RCs, invented the idea of doing the RC Show as a kind of bonding experience between the RCs and the freshman class, and it’s just a terrific custom. There have been quite a few years when I’ve been urged to participate in at least one sketch and didn’t have the good judgment to decline. The only way I’ve been able to survive in this job as long as I have is by blocking out all those memories immediately after they occur.

On the Class of 2013

It’s a terrific group of freshmen. It’s a very large class, actually, but they seem incredibly enthusiastic, incredibly diverse, extraordinarily friendly. One of the clichés about the academic world is that those of us who spend our lives here get older, and the students stay the same age. And I have to say, they’re seeming incredibly young to me now—substantially younger than my own children, both of whom graduated from college in the early 2000s. I have gone from, in my early years, feeling at some moments akin to an older brother of students, to feeling very, very paternal, at a time when students were roughly the same age as my kids. I’m glad not to have to reach the stage of feeling grandpaternal to them.

His advice to incoming students

I think my strongest piece of advice is to retain the sense of enthusiasm and optimism that they enter with. The opportunities are extraordinary for them. It’s very easy, over time, particularly because of the economic and career pressures that face this generation, to get caught up in a mechanistic view of education that, in the long run, I think is counterproductive. If—and I think many students do—they can retain the sense of wonder and enthusiasm and sheer potential enjoyment that they come to college with over the course of four years, they’ll do just fine.

His advice to the next dean of students

In general, I think my best advice is heavy doses of medication.