by William Sweet

“Global Valley” sounds like a contradiction, but the course, taught by Professors Lisa Brooks and Karen Sánchez-Eppler, delivers an ambitious amount of historical and cultural knowledge from sites barely a half-hour drive from campus.

“What would you do if you had to pick one thing to focus on in an introductory American studies course?” said Sánchez-Eppler. “A number of [faculty] had been doing more place-based research, and we had a lot of success with our New York City course, which involved a field trip to New York, and people loved it. So we thought: How about if we did here?”

The course starts with an overview of the geology, flora and fauna of the region and jumps into the history of early European settlement and interactions with Native Americans. A field trip this fall took students to Deerfield, Mass., to learn about the 1704 raid on the settlement and the changing perspectives on the “Deerfield Massacre” over the years. Kevin M. Sweeney, professor of American Studies and History, who has written about the raid, walked the village with students, discussing both Deerfield’s history and the history of how it came to be preserved and memorialized.

Students examining relics from Old Deerfield,

seen through a hole made in a door during the 1704 raid.

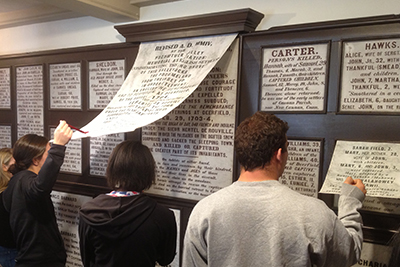

Among their stops students visited the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association’s Memorial Hall Museum, which displays a series of memorial plaques that were covered with new descriptions a decade ago. For example, one plaque reads Mary, adopted by an Indian, was named Walahowey. She married a savage, and became one; it’s now covered with a cloth that reads She married a Kanien’kehaka and adopted the culture, customs and language of her new community in Kahnawake. Students later read the public responses—including death threats—that erupted when the museum made these changes.

History in Deerfield. revised.

The course surveys subsequent benchmarks in Western Massachusetts’ history: preacher Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) and the Great Awakening in Northampton, Shays’ Rebellion of the 1780s, abolitionist Sojourner Truth’s time with a Utopian group in Florence. It also delves into the arts, as students explore the Emily Dickinson Museum, as well as the Hudson River School paintings by Thomas Cole at the Mead Art Museum.

The course looks at the industrial legacy of the region, and the role of racial, sex and gender politics in the Valley.

“I have never taken a class that incorporates the place and history being studied so well into the course assignments,” said Nicole Clay ’14.

Christopher Tamasi ’15 said he was surprised to find such a rich amount of history to explore in the region just beyond campus. “I grew up in a small suburb just south of Boston, so trips to Plymouth Plantation and other historical sites in the area were common, but my knowledge of the English settlement never reached far enough west into the Connecticut River Valley,” he said.

In particular, he appreciated learning the range of perspectives about colonial interactions with the Indians. “When the history of English settlement is discussed, the Native perspective is often left out the picture,” he said. “We have embraced all historical accounts in this class, which has allowed students to formulate their own opinions.”

The course grew out of practical considerations and a desire to foster community engagement.

“For a very long time we had a tradition of changing our introductory American studies every year or every other year, to keep doing things that were topical, either responding to the present moment or to research that individual faculty were engaged in,” said Sánchez-Eppler. “Designing a new one every other year was exciting and interesting, and it produced lots of great collaboration with colleagues, but it was also exhausting and frustrating. Each time you were basically beginning to understand what the course was about and how to do it when it was over and onto something else.” Faculty ultimately decided to create a perennial introductory course, allowing for greater depth and perspective from year to year.

One of this semester’s first projects involved a visit to Amherst College’s Archives and Special Collections, where students transcribed letters by local resident Elizabeth Whiting Phelps Huntington (1779–1847). The letters are part of a collection from the Porter-Phelps-Huntington House Museum in Hadley, Mass., on extended loan at the college. According to archivist Peter Nelson, the collection is one of the largest in the Archives, comprising more than 100 feet of files and 270 years of history. He said that the transcriptions will be entered as part of a digital archive available to researchers.

Transcribing letters of Elizabeth Whiting Phelps Huntington.

“It’s quite unusual to have such a continuous and rich and interconnected set of family papers—and not just family papers: the place has many, many objects,” Sánchez-Eppler said. “The work of social history is to try and understand the ordinary lives, and usually the evidence of our ordinary lives comes up being fragmented and scattered and really ephemeral. The Porter, Phelps and Huntington families stayed in that house from when they built it in the 1750s until 1968, when it was turned into a museum. There was no need to throw anything away, since nobody was moving.”

Working with Nelson, the class transcribed a selection of letters never before seen by the public. In them, Huntington writes to her 11 children, several of whom moved away during her lifetime.

Students later took to the streets of nearby Holyoke to study the Industrial Revolution and waves of immigration. They retraced the steps of past census-takers, to see how the city changed with the rise and fall of its paper mills.

“A lot of our students do community-based volunteer work in Holyoke,” Sánchez-Eppler said. “We hope that taking this course means that students who go off to work in the community will know a little bit more about its history.”