Interview by Peter Rooney

Ilan Stavans, described by his father in his most recent book as “muy prolífico,” is certainly living up to that billing this month.

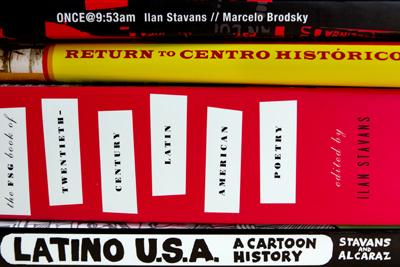

Return to Centro Histórico: A Mexican Jew Looks for His Roots (Rutgers), a photo-laden personal exploration of Mexico City’s downtown area, has just been published, along with the 15th anniversary edition of Latino USA: A Cartoon History (Basic Books), updated with a new chapter. Not to be overlooked is the paperback release of The FSG Book of Twentieth-Century Latin American Poetry (FSG), a compilation of verse in Spanish and English, with Stavans as editor and Amherst College poet Richard Wilbur among the translators. Stavans also is preparing an exhibition about his fotonovela Once@9:53am, an account of a devastating 1994 terrorist attack against the Jewish Community Center in Buenos Aires that killed 85 and left hundreds injured. That exhibit opens Sunday, April 29, at The National Yiddish Book Center (1021 West Street in Amherst).

|

Stavans, the Lewis-Sebring Professor of Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College, offered his thoughts on these recent projects as well as a number of other topics, including the evolving diversity of the Latino student body at Amherst and his predictions about Latino life in the United States. An edited transcript of the interview follows below.

Each of your projects could sustain an hour-long conversation, and they all are coming together in the next month or two. How did this come to be?

It‘s just serendipity that all of these projects have converged. These are projects that have been in the making for some time. The book that deals with returning to downtown Mexico City started as a magazine article two to three years ago. After it was published in Moment, there was interest from the publisher to turn it into a book. And the other projects have been coalescing in one way or another as well.

You dedicate Latino USA: A Cartoon History to your students at Amherst. Amherst College is more diverse than ever and includes about 200 Latinos out of a student body of about 1,800. From your perspective as a faculty member, what are some of the opportunities and challenges facing Latino students at Amherst?

When I first arrived at Amherst in the early ’90s there was already an attempt to diversify the student body, and I have been a happy witness to this transformation. It is not only that there are more Latinos at Amherst, but there are many other ethnic minorities and class minorities from other groups. Some fears [from] members of the faculty that this would decrease our rigor as an institution, that it would water down the tradition of excellence we have upheld for such a long time, have proven to be wrong. We are a much stronger, avant-garde and cutting-edge place today.

It is not an easy task to have a diverse Latino population at Amherst. As an institution, we still have much to learn. Latinos are a very heterogeneous and complex group. This is a minority that is not defined by race, language or a particular geographic location. Because we have those 200 or so Latinos coming from different walks of life, there are issues of education that need to be paid attention to. The fact that that someone comes from a protected, elite school and makes it to Amherst is different than a Latino from a public school who makes it here. That first meeting here between two [such] individuals can be as much of shock as meeting non-Latinos.

There is also a group of Latinos that I think is very important to acknowledge here: undocumented [immigrant] students. This is a population nationally of 5 to 7 million people who are of student age, and almost every higher education institution in this country has undocumented students. It is a fine line to walk—whether we want to call attention to this or not, as a college. It reminds me of the dilemma that a person who is gay has in coming out of the closet. These children grew up here; they are ours. We are at the cutting edge here when it comes to diversity, and with what we have accomplished in the last several years, we have a responsibility to reflect and explore this issue as well.

A stack of Ilan Stavans' latest projects

|

Can you offer any insight on what a typical day is like for you, in terms of juggling all the projects that you’re involved with?

I sometimes dodge the question by saying, “Who, me? I’m just doing what I’m supposed to do.” Sometimes I think, “In doing so many things, am I doing them with less attention, less concentration, less talent?” And my answer is, ”No.” There are some of us who spend our lives building one house, and others who spend life moving from one house to another and feeling those habitats are ours.

I think each of us has, maybe, written on [our] foreheads how many words we are going to be able to utter in a lifetime and how many words we are going to write. Maybe somebody up there screwed up the numbers and gave me more than my fair share.

As for my average day: I sleep my regular hours, 7 to 8 hours every night. You’ll see me in the gym. I go running. I have lunch with students or friends or my lovely wife. My weekends are with my kids or with friends watching movies or watching fútbol—soccer.

The FSG Book of Twentieth-Century Latin American Poetry was released in paperback this month, coinciding with National Poetry Month. What was the impetus behind this project?

We often recognize that Latin America has been an engine of extraordinary fiction—great novels, wonderful short stories—as well as great nonfiction books that deal with the magic and the exotic. But this recognition has come at the expense of another extraordinary facet of Latin American literature: poetry. Although Latin American poetry is less well known, the truth is that Latin America is much more than an exporter of fiction. It also is a machine of creating poems where politics and society come together and the exploration of our role in the universe is indulged. I wanted to create a portable library that would allow people to grasp some of the great poetic efforts that have been created over time.

In Return to Centro Histórico, you note that one in 5,000 Mexicans is Jewish, that there are perhaps about 35,000 Jews in Mexico and that [their] typical career paths are medicine, education and business. You also observe that many Mexican Jews are apolitical. Why is that, and does this describe you as well?

No, it doesn’t describe me. I am Mexican, and I’m very thankful for what the country gave my grandparents and parents. I left to come to the United States, but that doesn’t mean I have diminished my love for Mexico.

The Mexican Jewish community is small, insular and inward-looking. It has protected itself by not engaging in larger aspects of Mexican life. Only those who see themselves—and here’s where I fit—as rebels, or children who go against the parameters of their parents, have gotten involved in politics and the arts.

It seems that, in many parts of modern society, religion is not a core part of people’s identity. Yet it became part of yours as you entered young adulthood. How did that process take place? How important was religion to you during your childhood, and how important is it today?

My parents were not really Orthodox Jews. We kept the big holidays, but we were not religious. We lit Shabbat candles every Friday night, and our house was kosher, but if we went outside, we didn’t have to keep kosher. For us, culture was a form of religion. The fact that we [spoke] Yiddish and our ancestors were survivors or relatives of those who perished in the Holocaust meant that we had a duty to be Jewish, not religiously but culturally. We needed to prove to those who had tried to kill us that we had endured and survived and there was something inside us that we wanted to keep.

When I discovered religion in my youth, it was more an intellectual than a spiritual endeavor. I was very interested in the mechanics of how theology was built. How did we reach the conceptions of God [such] that we have differences between Catholicism, Protestantism, Judaism and Islam, from an intellectual perspective? I’m a believer, though a skeptical believer: I believe in God, with many doubts.

The Once@9:53am exhibit explores the circumstances of the bombing of the Jewish Cultural center, through the story of a photojournalist who happens to be in that neighborhood the morning of the bombing. It also explores anti-Semitism in Argentina. What is your sense of the prevalence and intensity of anti-Semitism in Latin American countries, perhaps compared to other regions of the world?

Nazi anti-Semitism is very different than Arab anti-Semitism, which is different from American anti-Semitism and European anti-Semitism. That’s why I think it’s time to talk about Hispanic anti-Semitism on its own terms. Going back to the Inquisition, the Catholic Church was manipulating information about Jews as Christ-killers and witnesses of the plight of Jesus. In Latin America, anti-Semitism is also combined with the hostility, mostly in left-wing circles, against the existence of the state of Israel, so anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism sometimes get conflated. What happened in Argentina in 1994 was an anti-Zionist attack that really passes as an anti-Semitic attack. It was against the Jewish Community Center, but it was motivated by forces that came from Hezbollah and Iran. Rather than going against Israel, they go against a community In Latin America that is ill-prepared in terms of security.

The Latino cartoon history book portrays many episodes and highlights of Latino impact and achievement in U.S. history, politics and culture, and the 15th anniversary edition brings things up to date with a new chapter. What do you predict will be the next chapter in Latino USA? A Latino president, perhaps?

[U.S. Latinos number] 50 million people, but I don’t think we can have a Latino president very soon. I hope I’m wrong, but the Latino community remains fractured culturally, politically and economically. That doesn’t mean a vice presidential candidate can’t be chosen. As the election approaches, it would be wise but challenging for the Republican candidate to choose a Latino running mate, because the immediate question would be, “What type of Latino—a Cuban, a Mexican or somebody else?”

Overall, I foresee a couple decades ahead of us in which Latinos finally enter the middle class in big numbers. If that happens, the whole country is going to better off. If it doesn’t happen, it will be bad for the whole country, because we will have a ghettoized Latino class with little access to education, and we will pay for that with riots, protests, increased crime and so on. It’s in the best interest of us all to make room for Latinos.

Bottom photo by Rob Mattson