By Peter Rooney

As more African-Americans are realizing they have German roots, and as Germans expand the notion of what it means to be German, a new academic discipline dedicated to examining the Black German experience recently had its third International Conference at Amherst College.

Christian Rogowski, professor of German. See high-resolution photo.

Christian Rogowski, a professor of German at Amherst College, together with Sara Lennox of U Mass, helped organize this year’s conference of the Black German Heritage & Research Association Convention, which was held August 8 to Saturday, August 10.

“The conference is unique,” Rogowski said, “because it brings together researchers who work on issues of ethnicity and racial diversity and the situation of blacks in Germany with people who themselves fall into that category, people with hyphenated identities such as Afro-German, African-American German or Black German.”

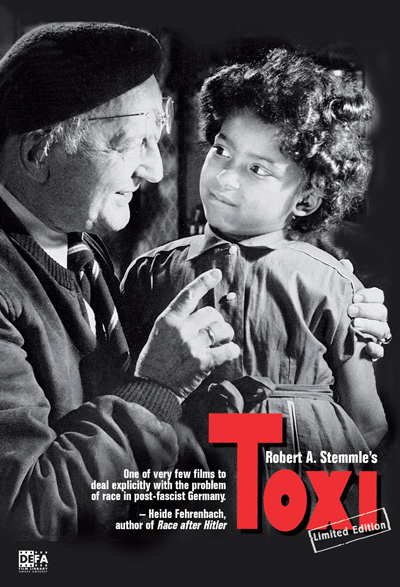

One highlight of the conference was a screening of the film “Toxi”, recently released on DVD by the DEFA Library of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The German movie from 1952 about an African-American girl who is born to a German mother after World War II, shows the impact that birth has on the girl, her family and the community that surrounds her. Angelica Fenner of the University of Toronto moderated a discussion about it.

DVD cover of the film Toxi. See high-resolution image.

Courtesy of the DEFA Film Library, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

“The film addresses the question that arose in the early 1950s about what to do with racially mixed children when they entered school,” Rogowski said “There was very little controversy when these children were with their families, but once they entered the public sphere that’s when things changed. The film is fascinating because it tries to generate sympathy for the predicament of the racially mixed child, but still advocates adoption. It ends with the (African-American) father coming and taking her ‘back’ to her supposed ‘home.’”

The field of Black Studies has gathered significant momentum from people who in researching their family histories have discovered that they were adopted as well, and that their birth mothers were German and their fathers were African-American G.I.s stationed in Germany, Rogowski said.

“In human terms, there are very moving stories that emerge from this field,” Rogowski said. “That’s something that has attracted me to it, this mix of academic research and this human dimension.”

Rogowski’s research focuses on German culture during the Weimar Republic, which preceded Hitler’s rise to power and offered a surprisingly accepting environment for African-American performers who had been subjected to segregation and institutionalized racism in the United States.

“There was a real fascination with American culture, for things like jazz and tap dance,” Rogowski said. “There were opportunities for African-American performers to work in an environment where there wasn’t systemic racism. Of course, you had racism in human interactions, but there was no Jim Crow legislation. In the 1920s in Germany, Blacks could go into restaurants and on trains without discrimination. Many performers experienced this as liberating.”

Although the Black Studies conference is only in its third year, the field itself traces its academic roots to the early 1980s, when American-Caribbean poet Audre Lorde was teaching a seminar course at the Freie Universität Berlin, and observed that several of her students were Germans of part-African heritage.

“A watershed publication called Farbe bekennen (translated in 1993 as Showing our Colors) emerged from that seminar and that really represents the beginning of a serious engagement with Black German Studies,” Rogowski said.

Current estimates for the number of Black Germans range from 300,000 to 500,000, in a country with a total population of about 82 million, and a growing number of Germans who claim heritage from other countries such as Turkey and Poland as well, Rogowski said.

“What Germany is now going through is a realization that it has become de facto multi-cultural, and clinging to a notion of designating identity by way of kinship becomes more problematic,” Rogowski said. “That means that Germany is shifting toward a more mainstream notion of politically defined citizenship.”