by Bill Sweet

This year Chile marked the 40th anniversary of the death of poet-statesman-Nobel Prizewinner Pablo Neruda with celebrations of his work and the exhumation of his body.

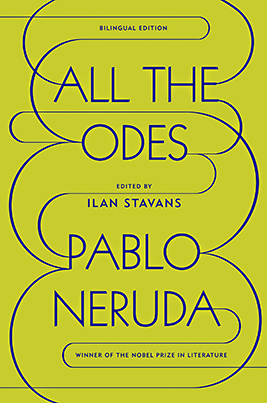

Just in time for the former —and having nothing to do with the latter, he assures us— Ilan Stavans, Lewis-Sebring Professor in Latin American and Latino Culture, is now celebrating the publication of a new volume of Neruda translations, All the Odes.

All the Odes is just what the name suggests: a collection of all 225 odes that Neruda wrote in his lifetime, composed on a weekly basis beginning in his late 40s. A follow-up to 2004’s The Poetry of Pablo Neruda, which Stavans also translated and edited, All the Odes marked a return to Neruda’s beloved, compelling and sometimes challenging work.

This is the first time that all of Neruda’s odes appear together in one volume.

“He wrote them as they emerged, and he would throw them in different collections,” Stavans said. The poems appear in the original Spanish, alongside English translations composed by Stavans and 17 other translators. Stavans gathered existing translations of some of the odes, and in some cases commissioned new translations.

Neruda is deceptively easy to translate, he said.

“He gives the impression that [the writing] is not complicated, but then you realize that every single word is placed strategically, and it becomes very complicated.”

It never would have occurred to Neruda to put together such a collection.

“A bit like Whitman, he was a writer of the moment,” Stavans said. “He would have 20 poems, and they would make a book, and then he would send it to the press. It wasn't like he organized a book around a particular topic or theme.”

For Neruda, poetry was just one element in a very public life. Neruda was a teenager when he first earned fame as a poet. But he also served as a diplomat and a senator for Chile’s Communist Party, and he was an adviser to President Salvador Allende.

“He saw himself as a prophet. He thought that his poetry channeled the emotions and the desires and the hopes of the people. In some of the columns he says that he's not speaking for himself alone, he is speaking for the entire nation, or for the entire continent, or for all of humankind,” Stavans said.

“Poets often are private people who see themselves looking at society from the outside, where this guy saw himself at the center of society,” he added.

The odes were often an attempt to step away from some of the grander topics.

“He wanted this to be a celebration of ordinary objects that surround us in real life: a pencil, your glasses, your socks, happiness, the onion, the watermelon, the movie theater.”

Weighing in at a massive 862 pages, All the Odes is “meant to be read like a dictionary, or like an encyclopedia,” Stavans said. “You go to whatever word of the day is your favorite word or the topic you’re exploring in the encyclopedia.”

“I think this is a manual for living,” he said. “What is it that makes us all enjoy the details of life? You open it up, and you realize there is an ode to the lover's hands, and you say, oh my God, yes! That could be my lover, too. Or an ode to french fries, just the sizzling of the potatoes in the oil just makes you see the french fries in a different way.”

Of course, when an editor sets out to publish all of anything, there’s the chance there will be some stinkers. Arguably, Neruda wasn’t always at his top form: in the case of some of his political poems, his values may not mesh with current sensibilities.

“There are some horrible odes here,” Stavans said, including some that heap praise on Lenin and Stalin.

“There is an ode to the trains in China,” he said. “But if you are going to put together all the odes, you have to put together all the odes. Even those ones you should not write home about. Some of them are of astonishing beauty, and others are not. He had a very pamphleteering, kind of cheap propaganda side,” Stavans said.

Neruda’s political entanglements resulted in his having to live in exile for years, and when he died, shortly after the 1973 coup that brought the dictator Augusto Pinochet to power, thousands of mourners defied the junta’s curfew and filled the streets in honor of Neruda.

Although Neruda’s relatives, friends and the Pablo Neruda Foundation (which manages his estate) all support the official story that Neruda succumbed to cancer in September 1973, a judge overseeing probes into hundreds of Pinochet-era deaths found sufficient cause to exhume Neruda’s body this year. Neruda's driver, Manuel Araya, alleges that doctors poisoned the poet.

In April, Neruda’s remains were unearthed, serenaded by classical musicians.

Regardless of what the exhumers determine about his death, Neruda’s poetry is deathless.

“He is endlessly beloved by young people. There is something very youthful in him, very much the vibrancy when it comes to celebrating newness and originality,” he said. “I really think that there are some of these odes, that if you read them at a crucial time in your life, they really are medicine. They can change you, they can make you see things differently. They’re just beautiful.”

Extra: read Philadelphia Inquirer columnist John Timpane's review here.