Abiodun, who is from the Yorubaland region of Africa, explained that while the camera was adept at photographing his wife, who is of European descent, his image always, as he wrote, “looked like a black silhouette.” He adds, “My image was framed literally, metaphorically, and aesthetically by this ‘point and shoot’ camera—a supposedly accurate technological instrument that seemed to work for just about everybody but me.”

In his book, Abiodun also emphasizes that it is necessary to understand a culture’s language to analyze its art, something he believes few have done in the field of African art.

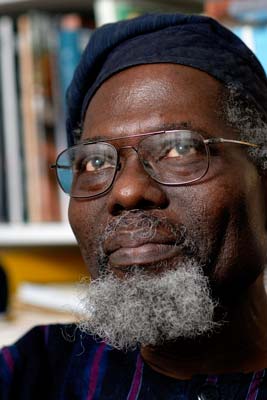

Abiodun, the John C. Newton Professor of the History of Art and Black Studies, has authored more than 40 books and articles on African art, and he has led a number of African art organizations. In 2011, he received the Leadership Award of the Arts Council of the African Studies Association.

Abiodun spoke to Office of Communications intern Nate Gordon about his new book.

Why did you write this book?

As an art historian who is also a Yoruba culture bearer, I’ve always thought that Yoruba language and culture should be critical methodological tools in the study and understanding of Yoruba art. [Scholars] work hardest at expressing African meanings in colonial languages, which is a less-than-subtle indication of the privileged status of those languages over African languages. This supposed superiority of colonial languages over African languages has effectively discouraged African scholars from incorporating their mother tongue into their research. There’s no reason why the bar for academic excellence in African art studies should be lower than what’s acceptable in western art historical studies.

How do you hope your book changes African art and the study of art in general?

All too often, the question is asked, “Why do African cultures not have terms, or not have words or concepts for art, for aesthetics, for style, and so on?” Scholars use imagined stereotypes to justify their avoidance of African languages. So, I’m hoping this will get scholars moving. If you don’t study a language or a culture, you will never know if [that culture] has words for something. … If a community of scholars finds it offensive or finds it impractical or finds it unnecessary to use an indigenous language in understanding African art, does this mean the colonial legacy still lives on?

What was your process of putting this book together?

[Because] I had a traditional education I was able to participate in festivals, rituals, where art forms were used. Also, the fact that I taught at the Yoruba university, the University of Ife, was very important [because] I actually taught Yoruba art in Yoruba language. Not in English, not in French. Yoruba art in Yoruba language. So, this is a culmination of all these experiences.

How do you think the average American views African art?

The average American view is incomplete because they look at it, very much, from the eyes of Picasso [and other famous western artists]. The whole thing goes back to the colonial mentality, which punishes an indigenous scholar for introducing an indigenous language into the study of art. It should not be that way.