Sports, Illustrated

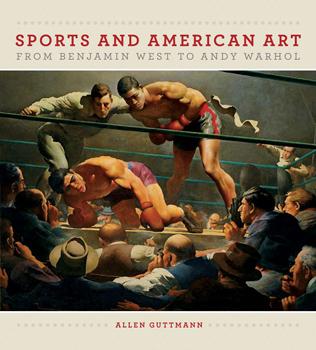

Sports and American Art from Benjamin West to Andy Warhol, by Allen Guttmann, the Emily C. Jordan Folger Professor of English and American Studies (University of Massachusetts Press)

Reviewed by Elizabeth E. Barker

|

[Art] The volume’s modest size—a pleasing, squarish 8 by 9 inches—belies its monumental erudition. Packed into its 277 pages are four interwoven narratives, each of which might conceivably have stood alone: a lucid and succinct history of the United States; a more detailed and equally masterful history of American sports; a brief history of American art; and an examination of dozens of specific American paintings, prints and sculptures depicting sports. Together, the four narratives map a wide terrain that has hitherto been little explored and that now, thanks to this volume, seems likely to become a site for more frequent scholarly consideration.

It is an ambitious project. But Allen Guttmann is the right man for the job. As an English and American studies professor at Amherst, he has explored the history of sports both in his teaching and in previous publications, including Sports: The First Five Millennia and From Ritual to Record: The Nature of Modern Sports.

In Sports and American Art, Guttmann traverses four centuries of American history, considering the imported pastimes of the Colonial era (such as cricket); the entrepreneurs who shaped distinctly American sports in the young republic (including “pedestrian” races); the rationally organized, urban-centered games of the industrial revolution (such as basketball); and the democratization and globalization of sports (such as tennis) in the modern era. He concludes with an eye to extreme “postmodern” sports (such as snowboarding).

Guttman lingers, appropriately, on the great American painters of athletes: Homer, Eakins and Bellows. He also introduces lesser-known works, including James Henry Daugherty’s revelatory, Futurist-style Three Base Hit.

Not surprisingly, given Amherst’s pioneering commitment to physical education, Guttman also mentions the college. We learn that in the 1890s, Amherst had two African-American players on its football team, played the touring African-American Cuban Giants in baseball and became an early member of an intercollegiate basketball league less than a decade after the game’s invention.

Guttmann doesn’t mince words: he describes a portrait by Gilbert Stuart, for example, as “cloyingly saccharine.” But he doesn’t waste or misplace words, either. His prose is direct, engaging, conversational and often very funny. He moves deftly across historical periods, providing enough information to make his points, but he never belabors the text with unnecessary details.

As a result, the book combines deceptively simple statements about long historical periods with a series of tantalizing tidbits, too numerous to list here, but too irresistible to omit altogether. Who knew that Puritans played soccer barefoot on the beaches of Massachusetts in the 1680s? Or that lawn tennis was first played on an hourglass-shaped court in the 1870s—and called (thankfully, only by its inventor) “Sphairistikè”? Or that girls’ high school basketball grew more popular than high school and college football in Iowa in the 1920s?

Sports and American Art eludes easy categorization. It is not a work of art history. Such a text would place the art in the foreground and use it as a window through which to view each era’s social, cultural and political landscape. Guttmann takes a different approach. He places society, sport and art history as the successive lenses, layered one before another, through which to view each work of art. Positioned that way, each art object appears like letters on an eye chart viewed through the superimposed lenses of an optometrist’s diagnostic headset: clearer and more legible, yet also slightly more distant. It is a revealing vision, captured in a book I found hard to put down.

Barker is director and chief curator of Amherst’s Mead Art Museum.