Picture This

At the Mead, we like to say that our collection spans continents and centuries: here you can find more than 19,000 cultural artifacts from Africa, Asia and the Americas, as well as European and Russian art, representing thousands of years of history. In fact, our collection is a physical link with human history, or at least a portion of it. Some works demonstrate how people ate food or decorated drinking vessels, others reveal how artists grapple with the beauty and wonder of nature. Art helps students contemplate the picture of human activity through the ages, providing clues and context for grand historical events and offering glimpses of everyday lives. At its core, the Mead’s collection tells us about ourselves: where we’ve come from, how we’ve changed (or not) and where there’s room to improve.

Your Challenge:

Below are images of three objects in the Mead’s collection. Your job is to guess the time period in which each was created; the medium; and what it depicts (for #2 and #3) or what 19th-century French painting it references (#1). Send your answers to magazine@amherst.edu. Anyone who answers correctly will be entered to win one poster of a Mead artwork. Details about the three objects will appear in the next issue.

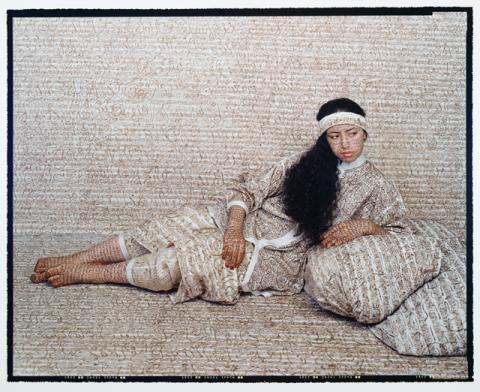

Object #1:

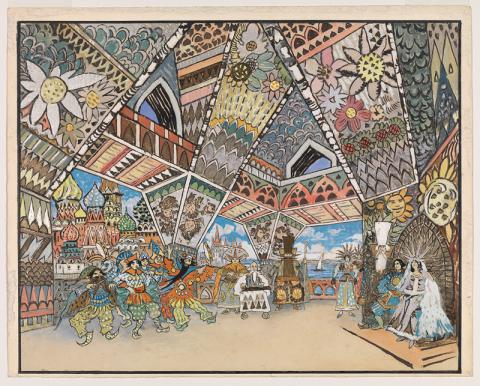

Object #2:

Object #3:

Last Quarter’s Answers

by Catherine Sanderson, Manwell Family Professor in Life Sciences (Psychology), who wrote the psychology contest

1. Why do Olympic bronze medalists show higher levels of happiness than Olympic silver medalists?

This finding is explained by counterfactual thinking, meaning people’s tendency to reflect differently on an outcome depending on how easily they can imagine a different outcome. Silver medalists can easily imagine doing just a bit better and winning a gold; bronze medalists can easily imagine doing just a bit worse and not winning a medal at all.

2. Why are people who get hugged regularly less likely to develop the common cold—even when they’ve all been directly exposed to a cold virus?

Hugging stimulates pressure receptors under the skin that trigger the release of oxytocin. Higher levels of oxytocin lead to decreases in heart rate, blood pressure and the stress hormones cortisol and norepinephrine. Higher levels of oxytocin also lead to improved immune function, which in turn increases the ability to fight off a cold.

3. Why do couples who meet online experience higher levels of marital satisfaction than couples who meet in more traditional ways?

Although research finds that couples who meet online have happier marriages and are less likely to get divorced, the specific factors that explain this finding are still under debate. One possibility is that couples who meet online are more motivated to get married (they’ve invested time, effort and money in finding a partner). Another is that they benefit from having access to a larger number of potential dating partners, which increases their likelihood of finding the right match.

4. Why are professional baseball players more likely to get hit by a pitch in August than in May?

Numerous studies demonstrate that as the temperature increases, so does the incidence of aggressive acts, including murder, rape, domestic violence and assault. In turn, batters are much more likely to get hit by a pitch on hot days (August) than on cooler ones (May), especially when more of the players on the pitcher’s own team had already been hit by the opposing pitcher (which suggests that retaliation is a driver for aggression).

5. Why do college students who take notes by hand perform better on exams than students who take notes using a laptop?

Research shows that students who take notes using a laptop tend to transcribe lectures verbatim rather than processing information and reframing it in their own words. When students hand-write, they are engaging in deeper learning and processing, which leads to better retention of the information.

Reader Answers

Thank you to all who entered the psychology contest. It was a pleasure to read all of your answers. Here are correct responses from three readers.

1. Why do Olympic bronze medalists show higher levels of happiness than Olympic silver medalists?

I am the only Amherst graduate who can personally answer your question, “Why do Olympic bronze medalists show higher levels of happiness than Olympic silver medalists?” I am an Olympic bronze medal winner—1972, Germany, sailing. The silver medalist could have a better chance to win the gold and dwells on what might have been. The bronze medal winner appreciates their achievement and what it symbolizes and is satisfied... despite the "what ifs." Often it was clear that the gold medal winner was going to win the gold, and the bronze medal winner was scrambling to win a medal. Often it’s not decided until the last of seven race, and the bronze medal winner is so appreciative of the results. On a personal note, I well remember standing on the medal stand being very appreciative and thankful, yet wistful, for what I was able to achieve. —Donald S. Cohan ’51

2. Why are people who get hugged regularly less likely to develop the common cold—even when they’ve all been directly exposed to a cold virus?

There's a lot to this one. Some of it goes all the way back to Bowlby and his primate research, which I remember reading about in my intro psych class with Robert Birney in 1964! Primates need physical contact, and overall, those that receive it are apt to be healthier than those that don't. As a specific application of the above, those who get hugged regularly, other things equal, are apt to have stronger immune systems than those who don't. I would hazard the guess that those hugged regularly are also likely to be happier in general than those not so blessed. And the regular exposure to cold viruses received through hugging would be apt to confer some kind of immunity to that virus after a while. —John Peirce ’67

3. Why do couples who meet online experience higher levels of marital satisfaction than couples who meet in more traditional ways?

Having met my husband in this manner, I should know, but am really just guessing . Possibly, corresponding online one can develop the relationship more analytically at first without emotion clouding the issue, and when the time comes to decide to marry or not, you have better judgment (using your mind versus your heart). —Ina King Arthur ’87

4. Why are professional baseball players more likely to get hit by a pitch in August than in May?

Editor's note: This question stumped all who submitted! The closest answer suggested that players are fresher in May weather than in August weather, when they are more likely to be tired and hot. The two most common guesses suggested that pitchers are more likely to take risks later in the season, because games matter more, and that "wear and tear" causes pitchers to lose accuracy as the season goes on.

5. Why do college students who take notes by hand perform better on exams than students who take notes using a laptop?

Not too long ago I was talking about this to a friend who has a daughter still in school. Those who take notes on a laptop will try to take them verbatim, without sorting out the wheat from the chaff, on the assumption that is possible or nearly possible to take down everything the lecturer says. Those taking notes longhand don't even try to take down everything; that would be impossible. Instead, as soon as the lecture starts, they start thinking about what are the more important aspects of the lecture, and what are the less important aspects. At the end of the day (or lecture) they are a couple of steps ahead of their seemingly more industrious colleagues, who tried to take down everything. Their notes have added value, because the students have already begun to identify for themselves the more important aspects of the subject. Being less voluminous, the longhand notes can also be more quickly perused. All of this was a given to those of us who grew up and went to college before computers. More raw information doesn't necessarily lead to more usable knowledge; in fact, quite the opposite in many cases! —John Peirce ’67