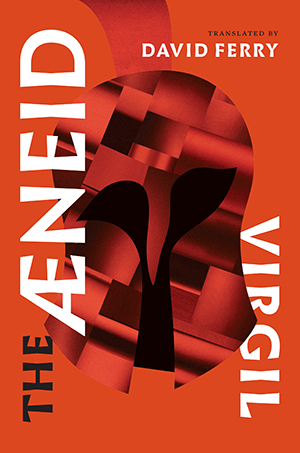

Now comes David Ferry ’46: a poet, and no ordinary poet. His new Aeneid is a miraculous resurrection of an ancient prophetic tale, richer than mere translation.

The Aeneid is perhaps discussed too much. It has been called the foundational epic of Rome, a panegyric to Caesar Augustus, propaganda in the Punic Wars and a screed against that nasty woman Cleopatra. Virgil’s Aeneid is a saga of refugees of war risking their lives on small boats in the Mediterranean; in 2017, that plain fact is an interpretation.

It contains multitudes, so the devil, or anyone else, can cite The Aeneid for his purpose. As they did with scripture, medieval Christian soothsayers opened their copies to random pages to foretell their Fate. By such bibliomancy, I could summon hard Truth written in cold steel, or breathtaking Beauty, on any page of Ferry’s Aeneid. But in horror or delight, every line of his majestic verse tastes metallic, the tang of melancholy.

When Aeneas encounters the shade of Dido in the mists of the underworld but can’t quite make her out: “... it was like seeing, / Or thinking you were seeing, the young moon rising / In the early days of its month, behind the clouds.”

In doubts and uncertainties before battle, Aeneas “was all at sea in his mind.” And I love Ferry’s masterly evocation of the fog of war, as his bloody adversary slips into a hypnagogic trance:

It’s as in sleep, in the quiet of the night,

Our languid eyelids close and in their dream

Won’t tell wherever we are nor where we’re going,

Or trying to go, nor can we get there where-

Ever where might be and who knows who it is

We maybe are, our legs gone weak, no way

To get there where? It was thus with Turnus.

Virgil’s Aeneid is difficult and beautiful; so is Ferry’s. Ferry breathes life into the Latin in a way that seems enchanted, as if he had collaborated with Virgil’s shade in Hades.

I love the gunmetal melancholy of Ferry’s verse. The episodes of The Aeneid are tragic: sons burying fathers, fathers burying their sons, good women done wrong, wars that might have been avoided, shipwreck and exile. If this is the founding mythos of an empire, it’s an empire that Virgil and Ferry both see coolly—the course of an empire for liberty, or an accidental empire, will not run smooth. It will prove difficult (in Ferry’s translation)

... to use your arts to be

The governor of the world, to bring it to peace,

Serenely maintained with order and with justice,

To spare the defeated and to bring an end

To war by vanquishing the proud.

This dreamtime ubiquity only makes sense, even if it’s hard to follow. Ferry’s Aeneid is an iteration of a poem written 2,000 years ago, by a poet recalling poems sung by nameless bards hundreds of years earlier than that, about events that already were ancient for Homer, and, for all that, it feels as if it had been commissioned for our troubled times.

The publisher’s blurb—wittingly?—offers a truly Virgilian prophecy: “This is an Aeneid our grandchildren will be reading.” Yes, but as a prophet warned Latinus, the king in Italy whom Aeneas overthrew to found Rome: “Strangers are coming here / To be your sons.” And your grandchildren.

Paul Statt is a Philadelphia-based writer.