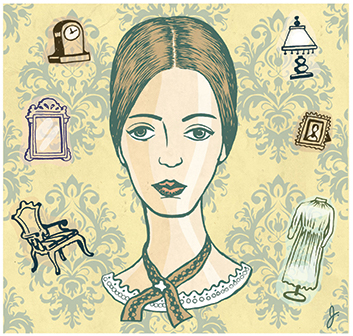

The 10-episode series Dickinson, from AppleTV+, takes a bold and comical look at the experiences of a teenage Emily Dickinson. But how does it play in the poet’s hometown?

The first season dropped on Nov. 1 with the launch of Apple’s new streaming service. The show centers on the young Emily, played by Hailee Steinfeld. But this isn’t a stiff 19th-century parlor drama. In the premiere, Emily takes a nighttime carriage ride with Death (Wiz Khalifa), and in a later episode, the Dickinson children throw a wild house party, during which she takes opium and dances with a human-sized bee. Twerking happens.

Reality Check

The Plot

In Episode 2, Emily Dickinson and Susan Gilbert don men’s clothes, transforming into “Lysander Periwinkle” and “Sir Tybalt Butterfly” to sneak into a men-only lecture by Amherst’s third president, Professor Edward Hitchcock. “Hey, do up my tie,” Dickinson asks Gilbert. Professor Karen Sánchez-Eppler corrects the record here: “The basic plot structure of this episode is wrong. Women could attend Hitchcock’s lectures.”

Days ahead of the poet’s 189th birthday in November, I watched the show with Karen Sánchez-Eppler, the L. Stanton Williams 1941 Professor of American Studies and English, who teaches a course on Dickinson, and Jane Wald, executive director of the Emily Dickinson Museum. Joining us were museum workers Madeline Clyne ’18, Brenna Macaray ’21 and Anna Plummer ’20.

We picked the second episode, “I Have Never Seen ‘Volcanoes,’” for the prominent part the College plays in the plot. “Women are forbidden at Amherst, so Emily and Sue get creative to attend a lecture,” goes the episode synopsis. Donning men’s clothes, Dickinson and her soon-to-be sister-in-law Susan Gilbert sneak into a lecture by Edward Hitchcock, a geology professor and the third Amherst president.

Throughout the show, historical inaccuracies run side-by-side with details that only Amherst eyes are likely to catch.

With the six of us gathered in a classroom in Chapin Hall, I turn on the computer projector. It doesn’t take long for Sánchez-Eppler to make a correction: “The basic plot structure of this episode is wrong,” she points out. “Women could attend Hitchcock’s lectures.”

In the accurate column: The classroom displays drawings by Orra White Hitchcock, who made large-scale scientific illustrations—“works of art in their own right,” according to a recent article in Smithsonian magazine—for her husband’s lectures.

In the partially accurate column: The lecture hall looks like a mashup of Johnson Chapel and the Octagon.

In the likely column, from a scene outside the lecture hall: “I actually think the two young men in their shirtsleeves boxing seems pretty right,” says Sánchez-Eppler.