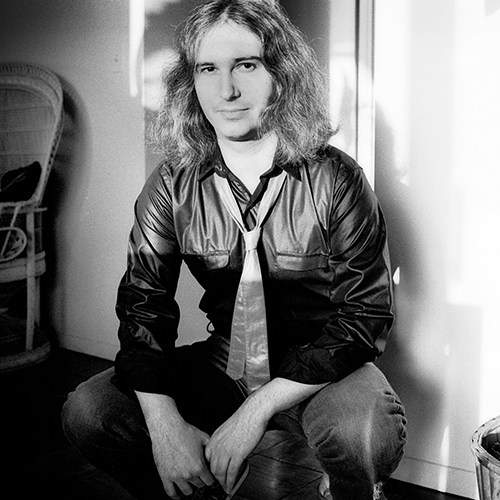

Steinman in 1981, four years after Bat Out of Hell and two before “Total Eclipse of the Heart.”

The passing of operatic rock composer, producer, arranger and playwright Jim Steinman ’69 this spring was especially poignant for those who knew him at Amherst and witnessed the unleashing of his irrepressible, boundary-breaking creative talent.

Rolling back the clock, I met Jim on my first day at Amherst in 1965. He was a skinny, introverted, overwrought kid from Hewlett, N.Y. Reclusive in his single room, he studied compulsively, perpetually clad in unwashed white jeans, a black belt and a deodorant-soaked white shirt.

In the early months, Jim was an unknown hermit in Stearns Hall. He first became a conversation piece with an astoundingly high mark on a world history exam. In hindsight, this was Jim’s 12-week studying phase.

Shortly, Jim began silently appearing around midnight in the doorway of the room I shared with the redoubtable Dennis Aftergut ’69. Dennis and I had gone to school together in the Midwest. I was an earnest student council president, in training for college wrestling. Dennis was a superb scholar with regular sleeping habits. To our consternation, the wraith of Hewlett would drift into our room on little cat feet, slump into our overstuffed green chair, and commence mumbling about literature, drama and opera until all hours.

Gradually, Jim’s mumbles transformed into surging midnightly monologues. Discourses on the meaning of life, or lack thereof. Absurdist impressions of professors and classmates. And eventually, howling, erudite, hilarious, acidic, manic riffs on everything—punctuated by Jim’s prestissimo percussion on the battered chair.

Soon our room became an after-hours Steinman Cabaret, starring a magnetic genius who emerged from his bat cave at night.

After scarcely appearing in classrooms for three years, Jim petitioned to spend his senior year on independent study, creating a rock musical as his thesis project. Legendarily, before ruling on his proposal, the faculty committee confronted Jim about his grades: “Please explain how, as a freshman, you ‘achieved’ 37 in physics and 19 in calculus.” Without hesitation, Jim shot back: “I was always better in science than math!”

Thus Dream Engine was born. The musical was Jim’s unique, Wagnerian brand of rock. It seized the audience with the penetrating, disturbing voice of an emerging artist as a young man, proclaiming the angst, turbulence and apocalyptic utopianism of the late 1960s. Startling imagery. Brilliant wordplay. Searing soliloquies. And propulsive, ear-drumming anthems.

Before the final performance, at Mount Holyoke, police interventions were threatened after word spread about the Dionysian nude scene. The cast opted for barely less revealing costuming. At intermission, New York producer Joseph Papp signed Steinman to a contract.

Our personal cultural counterpoint continued in early 1977, during my stint in the U.S. attorney general’s office with crusty constitutionalist Griffin Bell. Jim hailed me to the Kennedy Center for his Neverland performance in which Dream Engine’s tribe became the Lost Boys, and the roof-raising music was professionalized.

Later that year, Jim’s brilliance burst forth on a much larger stage. He and his huge voice Meat Loaf gave birth to global multiplatinum amazement with Bat Out of Hell, one of the biggest-selling debut albums ever. That commenced decades of public vibrating to his soaring music and profoundly witty, sardonic lyrics—with comic flip turns on tropes of language, lust and love. Memorably, Jim’s epic Paradise by the Dashboard Light featured Phil Rizzuto’s play-by-play of desire, outdone only by the velocity of Steinman’s irresistible refrains: “I swore that I would love you to the end of time! / So now I’m praying for the end of time / To hurry up and arrive....”

The cycle repeated in 1996. Jim dragged me from the intensity of Janet Reno’s office to the front row at Whistle Down the Wind at the Warner Theatre—a snake-handling revival musical, with Jim’s mesmerizing lyrics and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s music, including a future Olympics opening ceremony anthem.

The rest is history. The Dream Engine spirit was repackaged 50 years later as Jim Steinman’s Bat Out of Hell: The Musical, a raging stage show in London and New York. And Jim, a chart-topping Grammy winner and four-time nominee, was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, having sold more than 150 million albums recorded by Meat Loaf, Barbra Streisand, Celine Dion, Bonnie Tyler, Jim himself and many more.

Altogether, not bad for an introvert with a 37 in physics.

As Jim wrote in Bat Out of Hell: “I think somebody somewhere must be tolling a bell.”

Photograph by Gary Gershoff/Getty Images