The omnicrises of the past 12-plus months have so profoundly dampened American spirits that I think of our collective gloom as “2020-induced dysphoria.” Even the world of film, a fantasyscape for many, could not evade the thrashes of the last year: As more studios delayed releasing big, populist tentpoles, viewers continuously lost out on the chance to enjoy fun action flicks and low-stakes comedies that might have helped offset some of the woes of pandemic isolation. Thus, many of the movies that did debut in 2020 were the types one could only describe as “misery porn”—smaller but heavier features that navigated topics such as abuse, genocide, injustice and dementia, among other pounding horrors. Only a masochist could marathon them.

Yet, Chloé Zhao’s neo-Western drama Nomadland, about a widow who loses her livelihood and becomes a van-dwelling drifter, also happens to be the most life-affirming film of 2020. Far from exploitative, the film avoids mawkish and sensationalist tropes, instead relying on the breathtaking naturalism of its setting (and largely nonprofessional supporting cast) to tell the story of an aging woman finding solace on the open road. It won two Golden Globes and is an Oscar nominee for best picture.

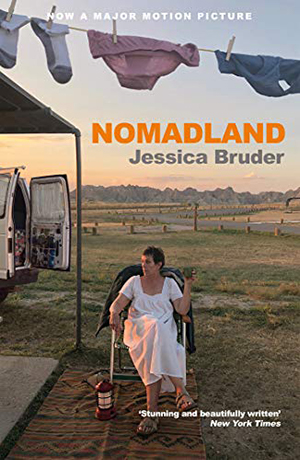

Nomadland

A film by Chloé Zhao

Based on the book by Jessica Bruder ’00

Searchlight Pictures

The film is adapted from journalist Jessica Bruder ’00’s 2017 nonfiction book of the same name, which chronicles the subculture of largely white, older Americans who traverse the U.S. seeking gig work. (It was the June 2018 feature for the Amherst Reads book club.) The film version dramatizes and specificizes its source material, focusing on an invented protagonist inspired by these post-Great Recession survivalists. Zhao’s resolutely independent Fern (Frances McDormand) bears the grit and stoicism of a 19th-century pioneer shielded only by a covered wagon.

Fern has lost it all. Her husband, to illness. Her house, to economic devastation. Her job and community, to the caprices of capitalism. In 2011, following the dissolution of the Nevada mining town where she lived, Fern purchases a second-hand van and modifies the interior to serve as her new residence. (Bruder took the same approach for research purposes, christening her van “Halen” before following her subjects across the Western states.) We observe Fern retooling nearly every inch of the vehicle for maximum storage and functionality: Each possession must now carry a pragmatic purpose beyond a mere sentimental one. Shorn of vanity, she crops her hair and bundles herself in denim, flannel and canvas. McDormand exudes as much tender vulnerability as she does taciturn self-sufficiency while nurturing Fern’s nascent calluses.

Fern sets off across the American West, securing seasonal work as an Amazon warehouse laborer and a campgrounds coordinator, among other laborious short-term roles. (In her book, Bruder documents former retirees who pick fruit, fry hamburgers and guard oil fields, all for low wages.) Fern communes with fellow nomads, sharing supplies and survival strategies. She sleeps at rest stops and in parking lots. Her friendships are deeply felt, but fleeting, as no one ever migrates along the same routes. Most of these secondary characters are played by real-life wanderers, including Bruder’s interviewees Linda May and Swankie. Fern eventually develops a cagey affection for David (David Strathairn, Williams ’70), a hound dog of a man who retreated into nomadism to escape past shames.

Nomadland thrives via its microcosmic details and its macrocosmic beauties. Zhao (Mount Holyoke ’05) homes in on the minutiae of Fern’s everyday life, her camera and editing technique eagerly nibbling at the everyday objects that make this space a home, like an all-purpose bucket or a set of treasured heirloom dishes. But, for as deeply as she immerses us in Fern’s condensed habitat, Zhao also widely exposes us to the all-encompassing hugeness of the American landscape. Fern crosses looming rock towers and oceanic grass plains and infinite mauve skies.

In one of the most memorable sequences, the lens captures her illuminated under an ombré sunset as she breathes in the solitude and enormity of the desert around her. For a moment, she looks as sly as the goddess Diana herself. Fern doesn’t pity herself or lament her misfortunes. Instead, she revels in her liberation. We learn later in the film that she was never destined to stay in one place, that she bristles at stagnation. She’s not homeless but “houseless.” For others, putting down roots leads to growth. For Fern, roots lead to rot.

Bahr is a film and TV critic.