Many Amherst collaborations begin in college. This one was 40 years in the making.

Photographer Stephen Petegorsky ’75 and writer Naila Moreira ’00 met about five years ago, when Moreira invited Petegorsky to join a photography panel at Forbes Library in Northampton, where she was a writer-in-residence. Soon, he contributed a photograph to the cover of her 2017 poetry chapbook Water Street (Finishing Line Press). While visiting his studio, she saw his photos of preserved animal specimens.

“They were arresting; they were haunting,” recalls Moreira, who teaches at Smith. “His photos are big, metaphorically speaking. They offered a portal I was eager to go through.”

Clearstories

Photographs by Stephen Petegorsky ’75

Poems by Naila Moreira ’00

Terrain.org

That Northampton studio visit was the spark for Clearstories, a virtual exhibition in which Moreira’s poetry speaks to Petegorsky’s photographs, and vice versa.

“I was delighted when I learned Stephen and I share an alma mater,” Moreira says. “At Amherst, I studied geology as my major back when the specimens of the Beneski Museum were still housed in Pratt. I spent many an hour gazing at the skeletons, shells and stones. This project shares a flavor of that happy time.”

Here, they talk about Clearstories and offer two photo-poem combinations, both published with their permission.

Image

By Stephen Petegorsky ’75

Growing up in New York City, I was fascinated by the dioramas in the American Museum of Natural History. There, the science and art of taxidermy fueled my curiosity to no end.

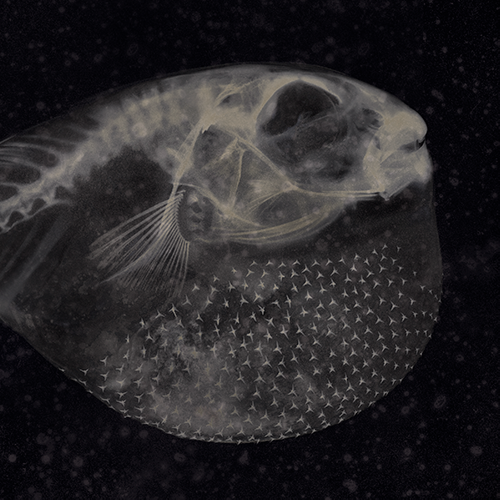

More than 20 years ago, a curator friend at the Wistariahurst museum in Holyoke, Mass., showed me hundreds of taxidermy specimens. The pathos was abundant; I was transported back to my childhood. I knew that I wanted to photograph them, and did so for two years.

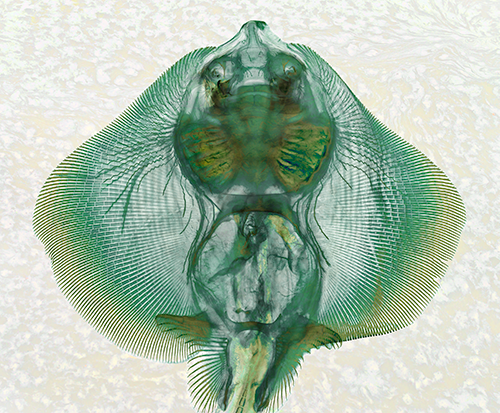

I kept my eyes open for other collections. When I found one at UMass, the curator also showed me things I had never heard of before: cleared and stained specimens. Small containers held what looked like reverse X-rays. Fish, birds, small mammals and reptiles had been placed in an enzyme solution that made the tissue transparent, and stains were applied to make bones and cartilage darker colors of red and blue. Once again I knew that I wanted to photograph them.

In architecture, a clerestory is a high section of a wall that contains windows above eye level. The purpose is to let in more light. As with taxidermy, the cleared and stained specimens allow me to see things about animals that I could not otherwise observe. They are beautiful and haunting. It is as though they are trying to tell me a story or to sing a song. These photographs are the visual impressions of what I hear.

Image

By Naila Moreira ’00

Stephen’s Clearstories images remind me of contemporary projects to photographically catalogue all animal life before it’s lost to extinction, such as National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore’s “Photo Ark” of more than 11,000 animals. By focusing on skeletons instead of living animals, Clearstories provides a grim mirror to these efforts in a provocative reminder of death.

However, environmental threat isn’t the only thing I see in these photos. In the interplay between life and death, animal and human, lie seeds of human mythmaking throughout time. Each animal’s anatomy serves also as a window into its own natural history and ecological niche.

Science art has burgeoned in recent years as a way to bridge the distance between the human psyche and our growing body of scientific knowledge. By pairing poems with photos, I aim to suggest resonances, lengthen engagement and deepen satisfaction by creating a ping-pong effect of ideas and relationships between image and text.

By imagining the animals of Clearstories simultaneously as archetypes of our deepest fears and hopes, and as mysteries of existence whose independent lives we can never fully reach or own, I seek to evoke both the wonder and the familiarity of these beings who share our earth.