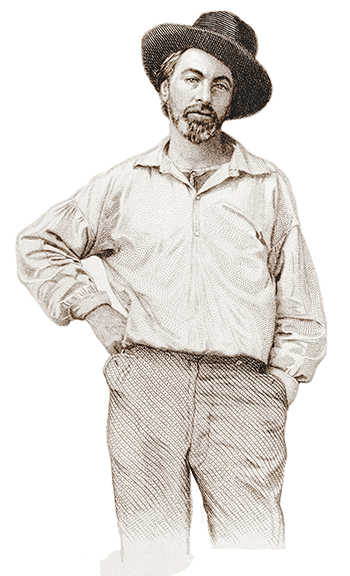

Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” is a celebration of egalitarian democracy. Throughout the 52 sections of his vast and sprawling poem, which he includes in Leaves of Grass, Whitman presents himself as the American embodiment of the Common Man. In fact, the frontispiece to Leaves of Grass shows Whitman in self-aware brazen protest—an oversize hat on his cocked head, his workshirt open at the neck, a scruffy pair of pants upon which his right hand is rather aggressively placed on his hip. He is unashamed to be exactly who he is and determined to do exactly as he pleases. As he says in Section 20, “I wear my hat as I please indoors or out.” My students take all of this in stride. They know about visual evidence.

It takes considerable prompting on my part, however, before they realize that the brash young man who is the dominant character of “Song of Myself” is actually composed of two quite different selves: an individual self and what might be termed a universal self.

The poem begins with a bold assertion of Whitman’s unique individual identity—“I celebrate myself, and sing myself”—but it moves swiftly to an assertion of universality: “For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.” In Section 24, Whitman’s two identities appear, with no sense of discomfort, in a single sentence: He is a unique individual, “of Manhattan the son,” and he is also a “kosmos,” encompassing many other Americans. As he proclaims in Section 51, “I contain multitudes.” The poem’s narrative structure is the continual back-and-forth between these two identities, between Whitman’s individual and universal selves.

My students require a bit of prompting to take that part in, but they manage.

Section 6 is, however, is the stumbling block. The back-and-forth between individual and universal celebrants of American democracy is suddenly interrupted by a mysterious assertion: “And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.” How’s that? How can Whitman persuade us to concur with this boldly counterintuitive statement?

The answer is deceptively simple. We are all a part of nature, and to nature we return. Section 52 ends with elegiac lines whose epiphanic images come as close as any poetry to persuading us that death is indeed an entirely natural and perhaps even a “lucky” phenomenon.

I depart as air, I shake my white locks at the runaway sun.

I effuse my flesh in eddies, and drift it in lacy jags.

I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love,

If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles.

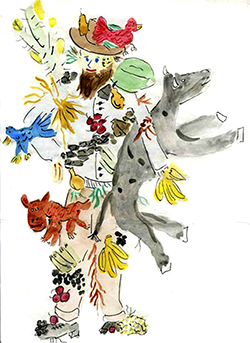

Not only do my students “get it,” they seem genuinely moved by these lines. En route to this solemnity, however, there are some more bumps in the road. Although few of the poem’s countless critics choose to emphasize its humor, “Song of Myself” is quite often very funny. And for my students, these comic moments pose a real problem, as in Section 31, which, I assert, is a comic version of Whitman’s idea that we are all a part of nature.

I find I incorporate gneiss, coal, long-threaded moss,

fruits, grains, esculant roots,

And am stucco’d with quadrupeds and birds all over.

The students answer: “Yes.” And so I do. Here it is. →

My students “get it.” They look up to the image and then down again to the words on the page. They laugh.

I like to think that my venture into visual art has helped my students to visualize the images of Section 52 and thereby to respond emotionally as well as intellectually to Whitman’s counterintuitive prophetic assertion that “to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.” I like also to think that I have become, for at least a minute or two, a successful teacher of poetry.

Guttmann is Amherst’s Emily C. Jordan Folger Professor of English and American Studies, Emeritus.