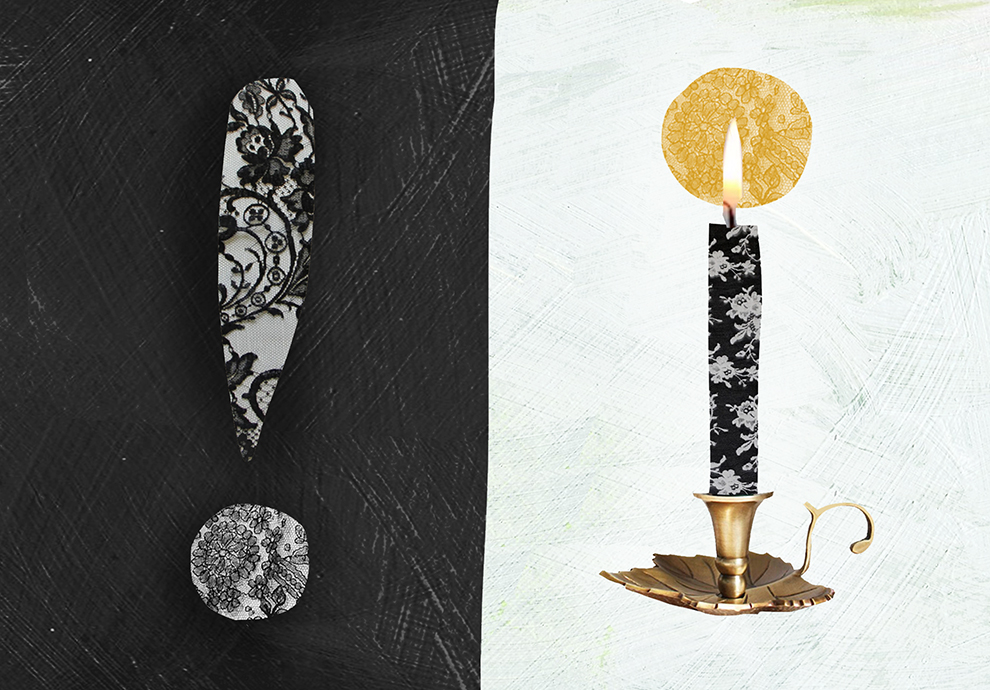

What’s up with Emily Dickinson’s exclamation points? As part of the Emily Dickinson Museum’s annual Tell It Slant poetry festival, some 150 people from around the world gathered to learn about the meaning behind the mark—which appears in Dickinson’s work 384 times. The virtual session was led by Moriel Rothman-Zecher, a poet, novelist and essayist, who shared takeaways from his upcoming article on the subject in the American Poetry Review.

In modern literature

Do we admire it today, though? Not so much, said Rothman-Zecher, who broke down its reception into four categories. Dialogic was the first: Exclamation points may be more acceptable in dialogue, to convey vocal excitement. Yet they have been maligned (the second category) for being excessive in poetry and prose. Rothman-Zecher cited theorist Theodore Adorno, who deemed exclamation points “a desperate written gesture that yearns in vain to transcend language.”

To convey sarcasm

For the third category, Rothman-Zecher quoted poets who’ve wrought sarcasm or irony out of the !, such Diane Seuss in this sonnet: “… He said and I quote ‘To be absent from the body is to be present / with the Lord!’ What does that look like exactly we cried. Are there chairs? Are there / lambs to tend? Because you know how we get when there are no lambs to tend!”

A slip of the pen

Rothman-Zecher said some scholars think that ! began as a slip of a pen. Medieval scribes would end certain sentences with the Latin Io, which signals joy or delight, but, at some point, the I was mistakenly placed over the o. Alternate theory: During the Renaissance, the Italian poet Iacopo Alpoleio da Urbisaglia rightly or wrongly declared himself the inventor of the exclamation point, which he dubbed punctus admirativus. In English: “mark of admiration.”

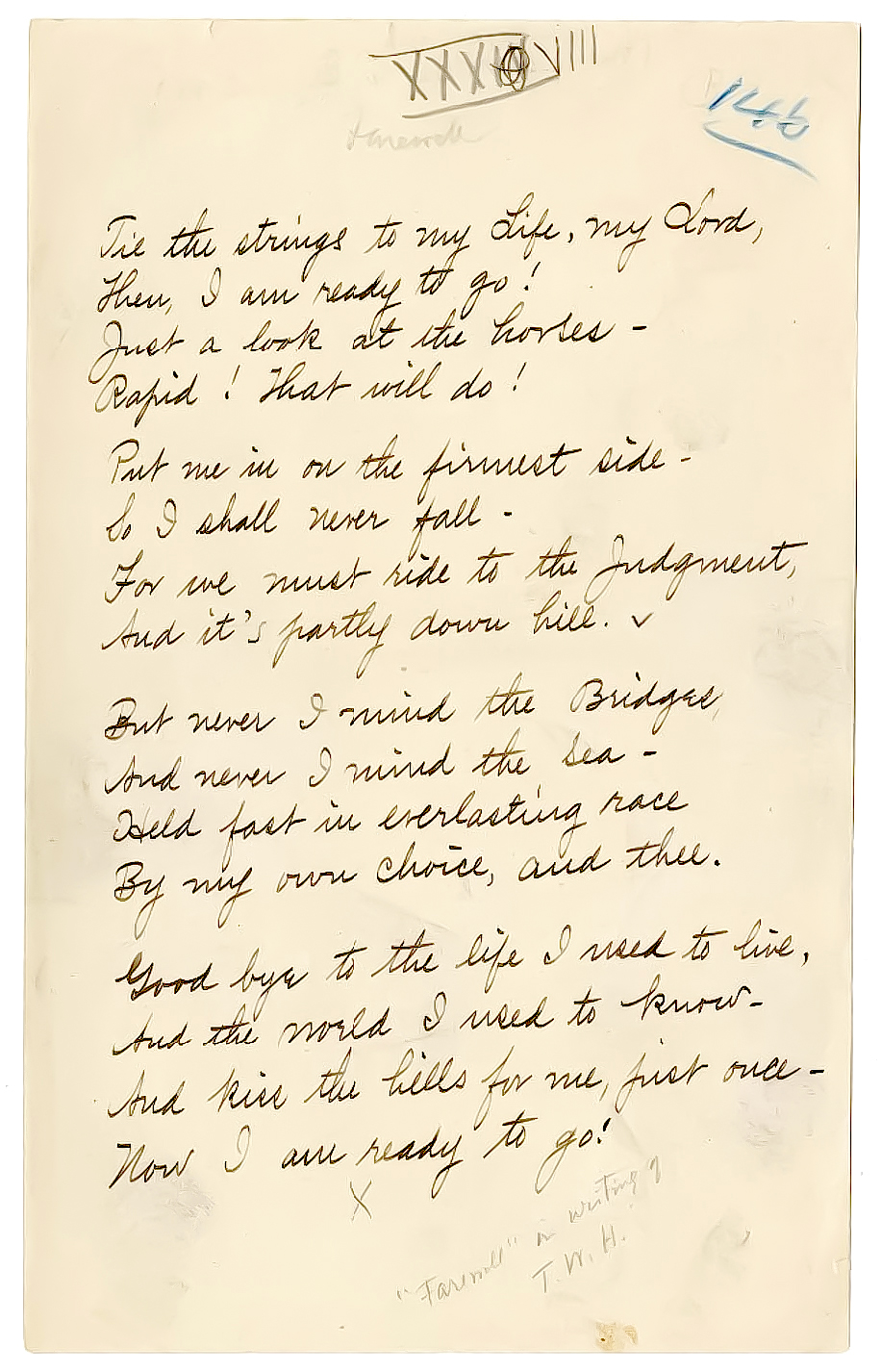

This Emily Dickinson poem may have been the last one she wrote. Do you see how it ends?

What it says about gender

One audience member asked whether exclamation points are coded as gendered, given how male critics disdained “female” effusiveness. Rothman-Zecher agreed, recalling that he’d once written enthusiastically to someone he hadn’t met yet, and they responded, “I was sure you were a woman based on how many exclamation points you used in your email.”

“Fare Forward, Travellers!”

Rothman-Zecher asked the people in the audience to take poetry volumes from their bookshelves, search for exclamation points and share the lines with the group. Dozens bobbed up in the chat section. A sampling: “Fare forward, travellers!” (T.S. Eliot); “sometimes they’ll sing / a trapgod hymn (what a first breath!),” from Danez Smith; “This afternoon, in the velvet waters, hundreds of white birds!” (Mary Oliver). And then Rothman-Zecher read from Dickinson’s poem F338A, possibly the final one she wrote. Which means her last mark may have been—wait for it!—an exclamation point: “Good bye to the life I used to live, / And the world I used to know. / And kiss the hills for me, just once—/ Now I am ready to go!”

To signal death

Dickinson lords over the last category, the “death-conscious” or “ecstatic” exclamation point, which glories in life despite—or because of—its finitude. In her poems, “you see the exclamation points jumping off the page,” said Rothman-Zecher. “You see it signaling something—and almost never is it dialogical, and almost never is it ironic.”

Illustrations by Katherine Streeter