November 3, 2010

Does Europe still matter in the 21st-century geopolitical and geostrategic world order? Or rather, where and how much does Europe matter in a globalized international system in which communism has collapsed, the United States is still a critical world player and new great powers—such as China, first and foremost—are rising in the global East?

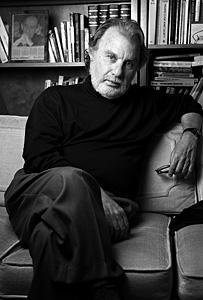

Ronald Tiersky, the Joseph B. Eastman ’04 Professor of Political Science, explores these questions in a new book published this fall.

The longtime scholar of French and European politics had more than enough issues to consider in European Foreign Policies: Does Europe Still Matter?, co-edited with John Van Oudenaren, head of the European division at the Library of Congress. The answer, he said, is that Europe matters a great deal even if its influence is “pressed from all directions.”

Written for students as well as specialists, the book features analyses from authoritative international experts on the topics of global peace and security, the foreign policies of the major European countries and the enduring partnership between the United States and the “Old Continent.” Tiersky, whom international news organization Reuters recently consulted for a story on Europe’s austerity measures, wrote the introduction, a chapter on France and, with Van Oudenaren, another chapter on Europe and Russia.

He discussed the book with Public Affairs’ Caroline Hanna and spoke about other issues affecting the countries across the pond.

|

How much does Europe currently matter in American foreign policy?

There’s no question that the center of gravity of the international system is moving from the Atlantic to the Pacific. China and other East Asian countries—India, of course—have become global players and are having a large effect on American power. But that doesn’t mean that American strategic policy can take Europe for granted. The EU is a global economy, with an aggregate gross domestic product that rivals the American GDP. The member states often disagree on the biggest strategic questions, but that doesn’t mean that Europe is no longer part of the global balance. The main issue in the long run is whether the Europeans really want to matter, whether they will formulate a new geopolitical ambition and whether they are willing to make the sacrifices necessary to match means with ends.

What kind of clout do you think Europe has in the world at the moment, given the global downturn and the rise of China?

Without a doubt, the rise of China is the most important new element in the world order. It’s the reason that American foreign policy has shifted its focus to the Pacific. The question is whether China’s rise will be careful and peaceful or whether the Chinese will become—even if they don’t want to—somewhat aggressive. The relationship between the United States and China is going to be the most important bilateral relationship in international politics and economics in the 21st century. But the U.S. will realize that it can’t deal with China and rising Asia alone. I think that the United States will find it a very good idea to be both an Atlantic power as well as a Pacific power.

What are some of the social challenges facing Europeans and the EU?

The biggest challenge is demography. The birthrates in a number of the EU countries are among the lowest in the world. Italy and Germany are particularly striking examples. The outlook for the European population is decline, and a declining population in modern times has meant, in general, a declining economy and a less consequential foreign policy. The second challenge is addressing the needs of the aging populations of Europe and the difficult financial situation associated with this. Increasing the legal retirement age is the biggest domestic policy issue in many European countries today. France’s decision to raise the retirement age, for example, resulted in months of massive strikes and street demonstrations—a classic French rebellion against government authority—although President Nicolas Sarkozy won the battle a few weeks ago. The last challenge is dealing with everything that has come out of the financial crisis. Will European economic growth rates enable the countries to pay for retirement pensions, maintain welfare states and subsidize health care systems? These challenges are all basically domestic, but they affect competitiveness in the international economy and Europe’s general position the geostrategic order.

Do you think the euro will survive?

|

The euro is the crowning achievement of European integration thus far. If the euro were abandoned, that would put into question the entire EU as it exists today. So what happens to the euro will be important not only in financial terms but as an indicator of political commitment to European integration as such. Moments of crisis, however, have generally led to more European integration, and we see today the German, French and new British governments working to craft agreements that would be more binding rather than a signal of accepting that the EU is fading. That’s the direction where all of this is heading: more rather than less Europe.

Have there been any important changes in European leadership in the financial crisis?

Absolutely. The new prime minister of Greece, George Papandreou, finally told the truth about how bad the deficits in the Greek government’s finances were, and this, I think, was a rather astounding innovation. He should be congratulated. By the way, Amherst has a stake in this, because George Papandreou is a member of the Class of 1975. He was actually a student in my “European Politics” course. I can’t claim credit for him speaking the truth, but having known him fairly well, his sense of responsibility doesn’t surprise me.

So what does the future hold for the EU?

This goes back to the question of Does Europe still matter?. In general, there’s going to be a lot more pressure on the Europeans from the outside, particularly in the area of economic competitiveness. The most plausible scenario, in my judgment, is that we’ll continue to see more Europe rather than less Europe. Whether increased integration will really give the EU and the Europeans more influence in the world order is not yet evident, but Europeans are likely to see the reasons why they ought to have a more determined level of geostrategic and geo-economic ambition. The whole question is, first of all, ambition and the willingness to sacrifice—meaning, as always, self-interest rightly understood. Are Europeans, both political elites and the people, satisfied enough to inhabit a continent on which everyone agrees the quality of life is extremely high and extremely pleasant? Are they content enough to ride along with the course of history, or will they find again the ambition to really matter?