By William Sweet

A century and a half ago, a member of the Amherst College Class of 1863 followed his chemistry professor into this country’s bloodiest conflict and returned in a coffin. After the body of Frazar Stearns—the son of the college’s fourth president, William Augustus Stearns—came back to Amherst, so did a cannon that he had helped reclaim from Confederate forces. It was a pale substitute for a 21-year-old with a promising future, but the “Amherst Cannon” would become a boon for historians.

This month marks the 150th anniversary of the March 14, 1862, Battle of New Bern, at which Stearns was killed. Historians will mark the occasion with a series of Civil War-themed events linked with the Emily Dickinson Museum, as well as an exhibition featuring the cannon, which has returned—albeit temporarily, they assure us— to Confederate territory.

Preparing the cannon for its trip to North Carolina

|

The cannon was given to Amherst College in April 1862, following the Union Army’s victory at New Bern. Trustees at the time vowed that “this loud-speaking trophy of victory… shall be preserved to be transmitted to all coming generations of the sons of Amherst College, as a monument of the heroism of those who have gone before them, and of the precious blood that has been spilled in suppressing this mad rebellion.”

The cannon was preserved, bearing a plaque honoring Stearns and other casualties of the battle, but over the years, it became hidden in plain sight, nestled in a stairwell in Morgan Hall. “It looked like a piece of plumbing,” laments Margaret R. Dakin, archives and special collections specialist for Amherst. Last year, the cannon was carefully packed and shipped to the North Carolina museum, where it has attracted renewed attention. Meanwhile, the Emily Dickinson Museum will sponsor an exhibition about the Amherst community’s involvement in the Civil War. Titled Frazar is Killed, it will open on March 28 in Frost Library.

“Frazar Stearns was kind of like the golden son,” said Jane Wald, executive director of the Emily Dickinson Museum.“He was the son of the president of the college in a small, close-knit educational community. [H]is fellow townspeople had invested a lot in the future of this young man.”

Stearns was among a group of Amherst students who signed up for service at the urging of their popular chemistry professor, William Smith Clark of the Class of 1848. Clark became an officer in the 21st Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, with Stearns as his adjutant.

On March 9, 1862, Frazar wrote his mother, “We are going to-morrow morning at daylight somewhere, — where, exactly, I don't know… always remember that any hour or any moment may bring you news that I am killed or dangerously wounded …These are horrible times, when every man’s hand is against his neighbor. But I have hope. Let the North pray more…”

It was his last letter home. Still recovering from the wound incurred at Roanoke, Stearns was with the 21st Regiment, among troops under the command of Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, as they moved into the North Carolina mainland, targeting New Bern, which had served as the capital of the North Carolina colonial government and then briefly as the state capital. Disembarking from the Neuse River about 16 miles downriver of New Bern on March 12, the 675 soldiers of the 21st led their brigade, discovering abandoned fortifications. On March 14, the 21st assaulted a brickyard and makeshift Confederate battery, allowing Union forces to take New Bern, which remained in Union control until the end of the war. This victory was not without cost: the 21st lost 19 men during the battle.

Clark wrote of the opening skirmish, which claimed his student’s life: “[T]he noblest of us all, my brave, efficient, faithful adjutant, First Lieutenant F. A. Stearns, of Company I, fell mortally wounded… As he was cheering on the men to charge upon the enemy across the railroad, he was struck by a ball from an English rifle…He lived about two hours and a half, though nearly unconscious from the loss of blood, and died without a struggle a little before noon.”

“They tell that Colonel Clark cried like a little child,” wrote Emily Dickinson, whose brother was a close friend of Frazar. “Austin is chilled—by Frazer’s murder—He says—his Brain keeps saying over ‘Frazer is killed’—‘Frazer is killed,’ just as Father told it—to Him. Two or three words of lead—that dropped so deep, they keep weighing—”

According to historian Polly Longsworth, Stearns wasn’t the only Amherst casualty at New Bern. Lt. Henry Ruben Pierce (Class of 1853) of the Fifth Rhode Island Volunteers was killed in the opening minute while leading a charge, and two more of the dead were residents of the Town of Amherst. But Stearns became a symbol in death: eulogized, lauded in state proclamations, honored with a funeral that rivaled Commencement in its attendance count.

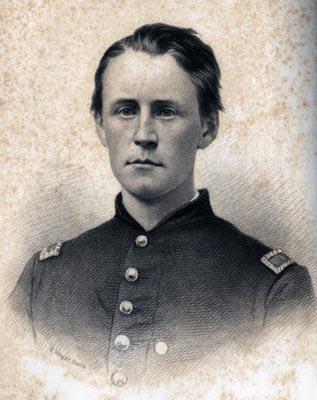

Frazar Stearns

|

“The bed on which he came was enclosed in a large casket shut entirely, and covered from head to foot with the sweetest flowers... Crowds came to tell him goodnight, choirs sang to him, pastors told how brave he was…,” Dickinson wrote. In April 1862, her father presided over the ceremony in which the 21st Regiment bequeathed the cannon to the college.

Grieving father and Amherst President William Augustus Stearns penned a popular volume based on his son’s remaining letters and the eulogies from the funeral, and those who never knew Frazar added their voices. Much of the response was shock and grief, and some was wartime fervor.

“If you’re trying to build support on the home front, you have to have heroes,” says Stables. “I think a reason that a lot was made of over [Stearns’ death] has a lot to do with building public support and recognizing these heroic feats.”

Frazar is Killed, will be open from March 28 to May 20 in Frost Library during regular library hours. There will be a panel discussion on March 29 at 4:30 p.m., moderated by author and Mount Holyoke lecturer Martha Ackmann, with Michael Kelly, head of Amherst’s Archives and Special Collections; Emily Dickinson biographer Polly Longsworth; Robert Romer ’52, local historian and professor emeritus of physics at Amherst; and Marianne Curling, consultant to the Amherst Historical Society. Also, on April 28, the Emily Dickinson Museum will host a “Living History Day” with a regiment of Civil War reenactors on the grounds of the museum from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. All events are free and open to the public.

Note: For those interested in more about Amherst College, Frazar Stearns, Emily Dickinson and the Civil War, Polly Longsworth’s 1999 essay “Brave Among the Bravest,” which covers this period in much more detail, is included in Passages of Time: Narratives in the History of Amherst College, edited by Douglas C. Wilson '62 and available from Amherst College Press.