“Everyone loves the sky,” says Jea Adams ’21.

The Amherst sophomore spent the summer working on advanced research in Professor Kate Follette’s astronomy lab, but still can’t help but giggle with excitement when she talks about recently getting her first telescope: a Celestron PowerSeeker.

“I haven’t completely figured it out yet, but I love looking up at the sky with it,” she says, speaking over the din of the Amherst Coffee afternoon rush. “I’ve managed to see Mars and the moon.”

Observing things firsthand—even ones that have been well-researched—is part of the allure of astronomy, says Adams. She had been interested in science since childhood, but it was an introductory class with Follette, assistant professor of astronomy, that convinced her to pursue the major.

“That was the one class where every day outside of class, I’d be pointing things out to my friends,” Adams says. “Doing that made me realize: this is what I really want to do. This is truly what I’m passionate about. There’s really never been anything else that made me feel that way.”

Professor Follette is hoping an increasing number of Amherst students—and the public, too—will be lured to science through their experiences in astronomy. The first step in that effort (which Follette hopes will eventually include a much larger telescope, a dome to house it and a director to manage it) was completed this summer when Amherst’s observation deck opened on top of the new Science Center. To make it friendly to all comers, the deck was designed to be fully accessible, down to the height of the telescopes.

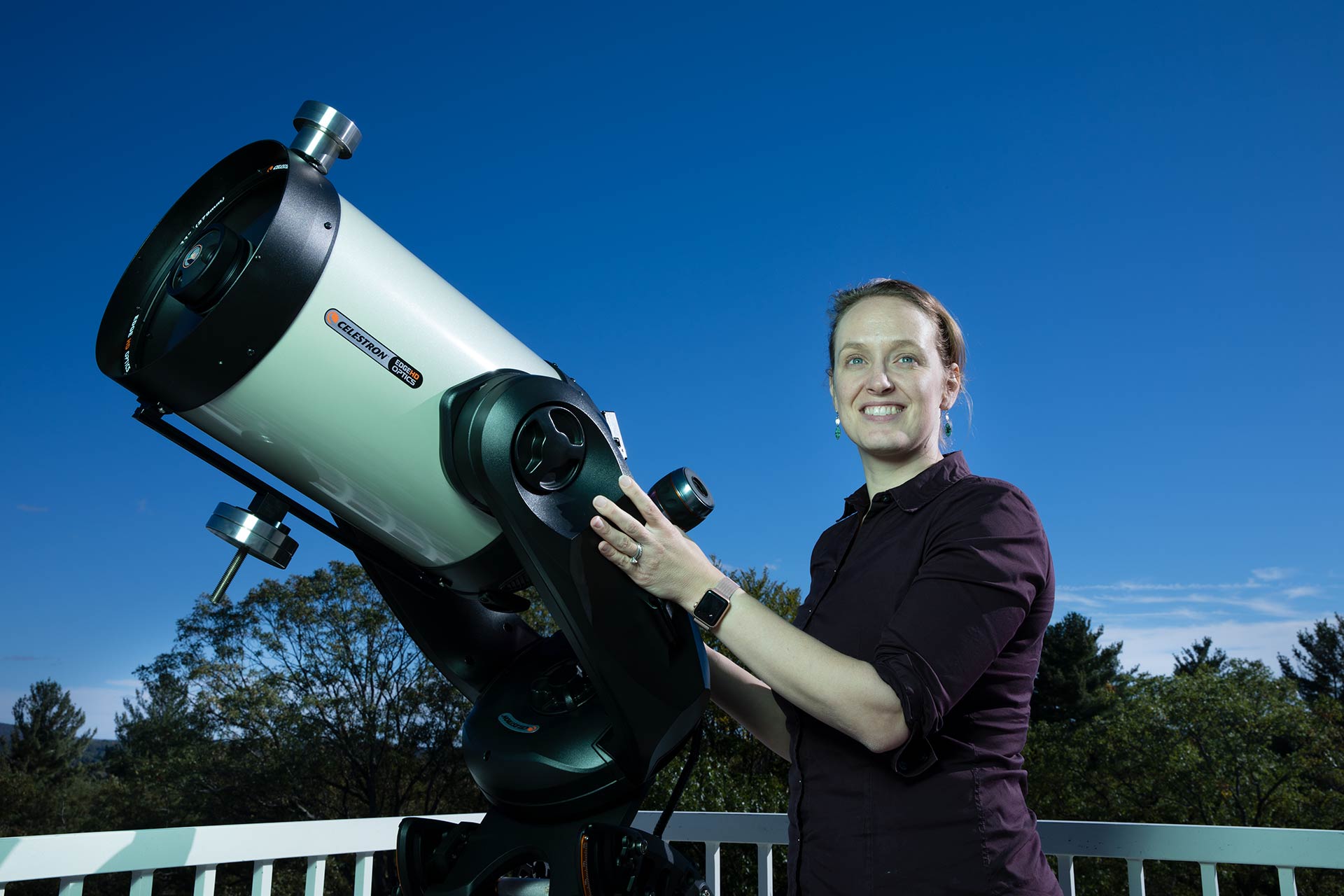

Located on the top floor, down a narrow hallway lined with the large equipment that helps power the building, the new observation deck could be mistaken for a rooftop patio. The flooring is large concrete pavers; there is a simple, functional guardrail around the edge. The centerpieces of this platform are six Celestron telescopes (with 11-inch diameter lenses that makes them much larger, and more capable of viewing faint astronomical objects, than Adams’), set at different heights. The observatory equipment and some construction costs were supported through a $150,000 grant from the George I Alden Trust. Eventually, the observatory will also feature a small computer lab right inside the door, where the telescopes can be operated and where students can study data.

Amherst's new observation deck officially opened on Saturday, October 20 during the Science Center Celebration with 3 p.m. tours.

Amherst has long had a place to see the stars. The Wilder Observatory, with its Clark & Sons 18-inch refracting telescope, was world-class when it was built in 1903. In the century since, though, modern science has developed well beyond the Clark & Sons technology. When she first saw the Wilder telescope, which she describes as a “beautiful antique piece of equipment,” Follette said she was taken aback to discover that people still had to pull ropes to adjust its position.

Times have changed in the astronomy world. To do her own research, Follette travels to Chile or Arizona to use telescopes that are eight meters across—the size of a building. She uses her time with these behemoths to look for Jupiter-like planets around other stars. By examining the colors of light emitted from a planet, through a relatively new observational technique called direct imaging, Follette can even extrapolate the composition of their atmosphere. Among other exciting discoveries, she recently identified an actively growing, so-called “baby planet” named LkCa 15 b.

In a light-saturated place such as Western Massachusetts, though, such advanced research is no longer possible.

“I think the role of small observatories has changed quite a bit,” Follette says. “There are publishable student research projects that you can do with small telescopes, but it’s no longer cutting-edge to work with small rooftop telescopes.”

Still, smaller observatories are valuable to the curriculum in a way comparable to chemistry or biology labs. With Smith, Middlebury and Williams Colleges, to name a few, all sporting excellent observatories, Follette notes that Amherst has “been behind the pack for a while.”

“It’s important for students to have an experience of using equipment and observing the sky,” says Follette. Not only are telescopes engaging, but they’re also a way for students to practice techniques before graduating to the large, and difficult-to-access, research telescopes, she says.

At the moment, students can only analyze data that Follette collects during research trips to larger facilities. The new telescopes will let her train students to do the observational astronomy that has formed the bulk of her work.

Follette herself didn’t set out to be an astronomer. As an undergraduate at Middlebury, she planned on majoring in language and joining the foreign service. Then an introductory astronomy class changed her plans.

“I’d never seen math applied in any kind of interesting or useful way before,” she says. “That class is what made me become a scientist.”

Follette’s goal is to create a similar culture of wonder and exploration at Amherst. As a result of her efforts, the astronomy program has gone from attracting one major every few years to having seven majors last year—a total on par with the number of physics majors.

The new observation deck will create opportunities not only for astronomy majors, but for non-majors and the public as well. It will feature a planetarium, and someday a telescope with a mirror of up to a meter in diameter.

“Eventually we will have a full modern observatory,” says Follette. “But half of a modern observatory is a big step in the right direction.”